STOP THE STEAL, Korean Style!

Supporters of Yoon Suk Yeol waving South Korean and American flags at a rally near the presidential residence in Seoul in March, 2025. JUNG YEON-JE / AFP - Getty Image

One of the weirdest sights in Seoul over the past year has been supporters of the disgraced and impeached former President, Yoon Suk Yeol, marching through the centre and holding banners saying (in English) ‘STOP THE STEAL’.

On many levels South Korea is modeled on America, and now, a significant proportion of its people are adopting contemporary America’s crazy disavowal of fact-based reality. Like lemmings, Yoon’s followers are following Trump and his cronies and the hordes of MAGA supporters over an epistemological precipice.

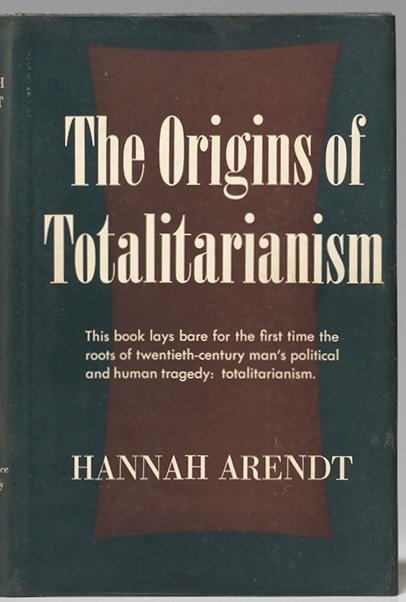

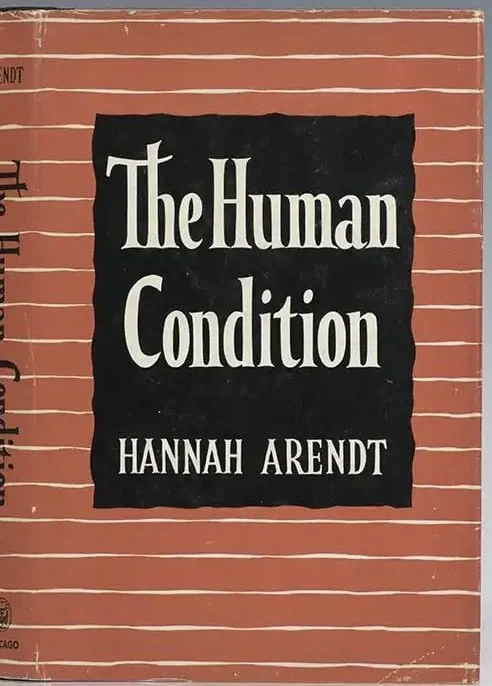

With this kind of craziness in mind, I decided to make a couple of works in my Book-Painting series based on the first edition covers of two of Hannah Arendt’s classic works: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) and The Human Condition (1958). Here they are:

‘Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951’), 2025, acrylic on canvas, 53 x 45.4 x 4cm.

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (1958), 2025, acrylic on canvas, 53 x 45.4 x 4cm

I chose to paint them in colors inspired by the originals - a sort of dried blood color. Here are these original covers:

In the light of the Korean STOP THE STEAL travesty, I thought it would be a good idea to share some quotations from these books. Although published in the 1950s, they still shed a scarily prescient light on the present. The Origins of Totalitarianism was written with the horrors of Nazism fresh in people’s minds and when Stalinism was a continuing nightmare, which was also the time of the Korean War, a conflict caused by the establishment of a new totalitarian regime in North Korea backed by Stalin, and one that has proven horribly enduring. The quotations I’ve chosen from the book The Origins focus on the role of mass propaganda in relation to politics. Arendt argues that “the masses are obsessed by a desire to escape from reality because in their essential homelessness they can no longer bear its accidental, incomprehensible aspects” (page 352). She uses this term “masses” throughout the book, which sound condescending nowadays. It goes without saying that Arendt and her peers (and you, dear reader) are not members of this ignorant social category. But perhaps she underestimated the extent to which everyone feels, as she puts it, “homeless” in modern society.

Here are some more quotations:

“The masses escape from reality is a verdict against the world in which they are forced to live and in which they cannot exist, since coincidence has become its supreme master and human beings need the constant transformation of chaotic and accidental conditions into a man-made pattern of relative consistency.” (page 353)

“[T]hey [the masses] do not believe in anything visible, in the reality of their own experience; they do not trust their eyes and ears but only their imagination, which may be caught by anything that is at once universal and consistent in itself. What convinces masses are not facts, and not even invented facts, but only the consistency of the system of which they are presumably part.” (Page 251)

”A mixture of gullibility and cynicism has been an outstanding characteristic of mob mentality before it became an everyday phenomenon of masses. In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing is true. The mixture in itself was remarkable enough, because it spelled the end of the illusion that gullibility was a weakness of unsuspecting primitive souls and cynicism the vice of the superior and refined minds. Mass propaganda discovered that its audience was ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to a be a lie anyhow......[U]under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.” (page 383).

This last quotation could be used word-for-word to describe the roots and methods of Trumpism. Such ‘populism’ certainly thrives in a climate of gullibility and cynicism. But there are obviously significant differences between what Arendt calls ‘totalitarianism’ and ‘populism’, above all because the latter is a response to a level of globalization that in the period Arendt was writing was absent. ‘Populism’ is also primarily a Western phenomenon, a backlash to the excesses and failures of neoliberalism. It is also effecting countries like South Korea that have brought so wholeheartedly into the myth of neoliberalism. But there is also an underlying continuity between ‘totalitarianism and ‘populism’: the feeling of powerlessness. Michael Cox, the Founding Director of LSE IDEAS, in an essay entitled ‘Understanding the Global Rise of Populism’ writes:

“populism is very much an expression in the West of a sense of powerlessness: the powerlessness of ordinary citizens when faced with massive changes going on all around them; but the powerlessness too of western leaders and politicians who really do not seem to have an answer to the many challenges facing the West right now. Many ordinary people might feel they have no control and express this by supporting populist movements and parties who promise to restore control to them.”

Arendt describes this pervasive sense of powerlessness as the consequence of a society in which people “are forced to live and in which they cannot exist, since coincidence has become its supreme master”, a society that deprives people of their fundamental need to constantly transform “chaotic and accidental conditions into a man-made pattern of relative consistency”. This deprivation is certainly one way of describing the appeal of conspiracy theories, which offers “the consistency of the system” and is, more generally, a symptom of the profound crisis meaningfulness precipitated by global neoliberalism .

To end, here is a quotation from Arendt’s The Human Condition which alludes to the source of the loss of a “pattern of relative consistency”. It also speaks directly to our present climate change crisis and to the fetishizing of science and technology as a solution. Arendt draws attention to how this delusion is informed by a “fateful repudiation of an Earth who was the Mother of all living creatures under the sky”, in other words, it is motivated by the deep craving to produce “ a man-made pattern of relative consistency” based on escape from the tyranny of nature:

“The earth is the very quintessence of the human condition, and earthly nature, for all we know, may be unique in the universe in providing human beings with a habitat in which that can move and breathe without effort and without artifice. The human artifice of the world separates human existence from all mere animal environment, but life itself is outside this artificial world, and through life man remains related to all other living organisms. For some time now, a great many scientific endeavors have been directed toward making life ‘artificial’, toward cutting the last tie through which even man belongs among the children of nature..... This future man, whom scientists tell us will produce in no more than a hundred years, seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human existence as it has been given”. (page 2)

REFERENCES

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, 1951 (Revised Edition, HBJ Books, 1973).

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Second Edition, The University of Chicago Press, 1958).

Michael Cox, ‘Understanding the Global Rise of Populism’, (2018), https://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/Assets/Documents/updates/LSE-IDEAS-Understanding-Global-Rise-of-Populism.pdf

Who can deny that America first conquered the world not with its armies of undercover agents but through the promiscuous circuit of its motion pictures? .... America is more than a particular culture, nation, or world power; it is a great theater of geometric projection in which the whole world now appears it itself in reduced form. Once a culture enters this space of projection there is no way back from the square to the cube. Eventually that culture becomes incomprehensible to itself. Or better, it becomes comprehensible to itself only from an ‘Americanized’ perspective, the fantasy of America standing in for the lost dimension. This is precisely why, in a world that increasingly understands itself through the medium of the screen, America’s postwar popular culture eventually appears as the only one that makes any sense. (page .146-7).

‘Ancient Apocalypse’ Now.

Some thoughts on watching the Netflix docuseries ‘Ancient Apocalypse’, including a somewhat controversial reference to North Korea.

Some thoughts on watching the Netflix docuseries ‘Ancient Apocalypse’, including a somewhat controversial reference to North Korea.

For those few of you who have been waiting, apologies for the long delay in posting on my blog. One reason is that I’ve been working on a new book, of which more in a future post. Another is that I’ve been busy in the studio, also more in a future blog. And another is that things have been getting so pear-shaped in the world that I’ve felt rather overwhelmed.

Fortunately, a Netflix docuseries has forced me to focus my attention and to share my thoughts.

The series (actually two series made between 2022 and 2024) is called ‘Ancient Apocalypse’, and the host is the best-selling English author Graham Hancock. He’s a very affable host. Very passionate and sincere. We get to see some weird and wonderful scenery and some amazing ruins.

The series, like the several books he’s written over the past 30 years, purports to give convincing evidence of something no archeologists seem to have noticed. According to Hancock, once upon a time there existed an advanced ancient civilization that was almost wiped out by a massive comet strike during the Younger Dryas, at the end of the last Ice Age, around 12,800 years ago. Some of the members of this civilization survived, and they traveled around the devastated world teaching what they knew to those scattered groups of more ‘primitive’ hunter-gatherers who had also survived. One of the things the survivors of the advanced civilization did was to bake into the new civilizations they were helping to found a warning about the inevitability of a future devastating comet strike, so humanity would be more prepared next time. Hence all the huge structures of more or less pyramidal shape dotted around the world that, Hancock asserts, are often much older than archaeologist claim, and are specifically oriented geographically towards certain celestial constellations. And hence, for example, the prevalence of snake-imagery, which he claims is a mythical visualization of a comet.

It must be stressed immediately that mainstream archaeology finds no compelling evidence that such a lost civilization ever existed. Nevertheless, there are certainly enough enigmatic holes and continual instances of revisions within the orthodox story of humanity’s development to warrant alternative hypotheses like Hancock’s. However, he goes so far as to claim that he is the victim of censorship and even of character assassination, that professional archaeologists have it in for him because of what he argues is a credible alternative explanation of ancient history, that is, of how we have got to where we are today. For Hancock has almost single-handedly created an alternative origin story of humanity, one that has made him quite wealthy, and now, with the Netflix series, even more wealthy and famous. Also notorious in some quarters, especially amongst those archaeologist who are aware of his theories. If you Google ‘Ancient Apocalypse’ or ‘Graham Hancock’ you can read a sample for yourself.

His narrative is basically a variation on the Atlantis myth, which was introduced into Western culture by Plato. Since the Ancient Greeks, Atlantis has risen and sunk beneath the waves of the human imagination, and nowadays Hancock doesn’t bandy the word ‘Atlantis’ around so much, having recognized that it has become associated with some dubious people whose ideas have been thoroughly debunked. He does not think of his ideas or of himself as in any way dubious. In fact, one gets the impression from his docuseries that he sees himself as a heroic, selfless outlier bringing the good news to a hungry people. He claims that the ‘experts’ are simply objecting to an ‘outsider’ who is impetuous enough to poach on their territory, and in the series he continuously asserts that mainstream archaeology is a kind of cabal intent on maintaining their spurious agreed upon narrative against credible alternatives.

This scenario reminds me of the Roman Catholic Church and the Protestant Reformation. Hancock is like one of the more radical non-conformist Protestants, and like them, he claims that his insights into the truth come through personal inspiration, rather than prior authority. He willingly acknowledges that his theory is based on a hunch, an intuition about what really happened millennia ago. But it has, so he claims, been corroborated by the facts. This faith in a subjective, personal relationship to revelation is also characteristic of the anti-authoritarian tendencies within the Reformation, and later of the Romantics, who challenged the emerging replacement for religion, a newly legitimated worldview based on reason and science. This demanded assent to an new authority, to the scientists and other experts who represented reason, and to the technological and bureaucratic structures which the new system spawned. But what increasing numbers of people in the West craved was something a bit more mythopoetic, a bit more exciting, a bit more controversial. They missed the sacred aura of religion. From the standpoint of an consciousness hungry for mythopoetic resonances, the rational, scientific worldview inevitably seems grey and disempowering, and the Romantics were just the first to challenge it through placing emphasis on the imagination, subjective experience, and instinct. Hancock feeds into the contemporary scepticism increasingly felt by many people towards all the boring ‘experts’, the professionals who dominate our lives, all those who compel us to conform to a conventional version of reality, the ‘official’ version we’ve been taught at school. We resent the gatekeepers within our society, the ‘parents’ if you like, who have the annoying habit of curbing our desires, our imaginations, and forcing us to toe the line, and who, we suspect, may not have our best interests at heart.

I remember when I was a teenager devouring Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods (1970), a massive bestseller which claimed the reason for humanity’s remarkable achievements starting millennia ago was a series of friendly visits from highly advanced aliens. Wonderful! This was so much more interesting that the dull history of kings and queens, Acts of Parliament, and warfare that I was being taught at school. It was so much more grist for my lively imagination, and also fed into my distaste for the authority-based, rational, bureaucratic, alienation society in which I was living. Hancock doesn’t talk about aliens, but his story is another iteration driven by the same basic motive, which is to make the past more interesting, more exciting, more mysterious, more sacred, more resonant, for all us alienated people of the present who feel like anonymous cogs in the wheel. All such stories can ultimately be traced back to the Romantics.

Failing to emphasis the fictional status of his narrative, as Hancock does, is a serious omission. But of course he can’t say its just fiction, because he wants his cake and to eat it too. He offers a counter-narrative to the one provided by rational scientific research, but he also wants his version to be credible according to those standards. He knows his audience would be much less interested if he cast his story as a fictional one, because that would leave in place the existing regime of facts. But Hancock doesn’t contest these given facts by presenting cogently reasoned corrective facts. Rather, he present his opinions as facts. He appeals to people who want to believe that a fact is nothing more than an opinion that’s gained traction amongst those who hold the reins of power.

Unfortunately, an opinion is not a fact. As the philosopher John Corvino argues in an issue of the online ‘The Philosophers’ Magazine’, when we ask: ‘“What is the difference between facts and opinions?” what we’re really asking is “What is the difference between statements of fact and statements of opinion?”’ As Corvino admits: the fact/opinion distinction is therefore ambiguous, ‘and in trying to explain it, people typically conflate it with other distinctions in the neighbourhood.’ He concludes by proposing the following working definitions:

A statement of fact is one that has objective content and is well-supported by the available evidence.

A statement of opinion is one whose content is either subjective or else not well supported by the available evidence.

According this definition, it seems clear that Hancock’s thesis is an opinion. Making this distinction is very important, because, as Corvino writes, ‘precise thinking is valuable for its own sake.’ Another reason is more pragmatic: ‘Despite its unclear meaning, the claim “That’s just your opinion” has a clear use: It is a conversation-stopper. It’s a way of diminishing a claim, reducing it to a mere matter of taste which lies beyond dispute. (De gustibus non est disputandum: there’s no disputing taste.)

The schism between objective content and taste also goes back to the Romantics. It was they who first elevated subjective taste above objectivity. The Romantics saw facts as fundamentally alienating. They drained color from the world. But at that time, there was no real danger that taste would ever trump objective content. The Romantics only sought to keep open a pathway along which taste could travel.

As several commentators have pointed out, it’s no coincidence that the Netflix series includes a couple of segments with the podcaster Joe Rogan. He’s one of the most influential online peddlers of the idea that we should ‘do our own research’, or that having an opinion is as valid as the ‘precise thinking’ that brings to light the facts, or ‘objective content....well-supported by the available evidence.’ The ‘research’ we do rarely has this goal in mind. Rather what we are trying to do, unconsciously, is exchange one external source of authority under whose control we chafe, for one that we find more conducive to our subjective taste. In practice, this also means we are conforming our taste to that of a what he consider a congenial sub-culture, or a chosen ‘tribe’. But if science has taught us anything, it is to be aware that we are amazingly skillful at fooling ourselves, and that we need well-defined methodologies for hedging against inevitable and unrecognized biases. Scepticism is of course valuable. Unthinking acceptance of the ‘given’ is wrong. But when this questioning becomes systemic, and taste replaces facts, we as a culture are in big trouble.

And then there’s the implicit racism of Hancock’s thesis, which has also been pointed out by many critics. I’m sure Hancock himself is not a racist. But there are unforeseen consequences to his theory that are certainly racist, consequences he himself came to tacitly acknowledge. For example, he used to describe the surviving members of the lost civilization as ‘light’ skinned and bearded. Now he just says ‘bearded.’ But obviously, there’s an implicit racist implication in the idea that one advanced people from a particular region, who happen to share the same pigmentation as Hancock and Westerners, taught all the others, with darker pigmentation and who didn’t have the nonce to build anything bigger than a shack, how to construct massive pyramids. Couldn’t the aggregate growth in knowledge have evolved gradually via multiple channels of communication and cross-fertilization of ideas and technology from different cultures? After all, even within the orthodox version of history we are talking about tens of thousands of years.

So, Graham Hancock, I humbly suggest that your theory is an opinion. And I say this in order to diminish it to a ‘mere matter of taste which lies beyond dispute.’

*

But what I’d like to do in this final section is suggest that Hancock’s theory is actually factual, that it’s not just an opinion, and that it does indeed have ‘objective content and is well-supported by the available evidence.’

Yes! ‘Ancient Apocalypse’ is all true.

But what kind of lost advanced civilization are we really talking about? Hancock seems to assume it was wholly benign. The survivors were like a team of boy scout leaders bent on teaching an adopted group of wayward youngsters how to do knots, build a campfire, help old ladies take out their garbage, etc. But what if they weren’t such goody-goodies?

Hancock argues that survivors of the lost civilization also taught other less advanced survivors how to farm the land. One of the strange discoveries of (admittedly mainstream) archaeology is that the shift from hunter-gatherer to agrarian society wasn’t a straightforward net gain for those involved. People’s lives were actually worse off once they adopted farming and became sedentary. People had to work much harder. Average life expectancy went down. Private property was invented, and unequal and oppressive hierarchies became entrenched.

Yes. So OK, they taught us agriculture. Thanks a lot. But perhaps we were happier when we were hunting and gathering.

Hancock also stresses sky and sun worship. This too, was a key lesson in the advance of humanity. But is it? As archaeologist and anthropologists show (again, mainstream experts), this form of religious practice supplanted animism. But was this a net gain for humanity? The jury is out. In fact, there are those (experts) who argue that animism is the most effective and benign way of theorizing humanity’s relationship to the world - to the non-human - because it treats us humans as part of the whole living ecosystem, rather than lifting us up to the top a pyramid where we can feel closer to the sun (and make plenty of human sacrifices to ensure people toe the line).

And, by the way, how were the spectacular monuments Hancock tours us around actually built? He never mentions the probably malign logistics of building the massive structures he shows us. He says that they must have involved a lot of people’s labor, a high level of collective organization - which would have been far beyond the capabilities of mere hunter-gatherers. But what kind of labor was it? Were they all volunteers? I doubt it. These monuments were probably the work of countless slaves who had been brutally forced to construct them.

The survivors of the lost ancient civilization used their superior know-how, and the threat of a new apocalypse, to enslave all the people’s they came in contact with. The snake is not a symbol that signals the existence of a an enlightened civilization, but actually the symbol of a brutal one.

OK. Here’s my final shocker: What if the lost civilization was actually like North Korea, or at least, what if the survivors, traumatized by the comet apocalypse. set about creating a kind of Paleo-North Korea?

I’m not entirely joking.

As readers of my blog known, I live within hypothetical walking distance of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, although if I actually tried to head north, I wouldn’t get very far, due to the presence of a very formidable and lethal Demilitarized Zone. But this means I often compare things to my neighbors. It can be salutary.

You can see the parallels already, I hope. There are more.

North Korean has developed an elaborate quasi-religious cult of leadership. A major aspect of its ability to maintain control over its subjects is the way it weaves a narrative in which the Kim dynasty is cast as composed of exemplary, godlike beings. Doesn’t this seem to be what the survivors of the lost civilization also instilled in the hapless hunter-gatherers they conquered. Isn’t this a major reason why of they could control the minds and bodies of their subjects?

I’ve mentioned before in my blog (see: ‘North Korea. ‘Theater State’, June 21, 2020) the anthropologist Clifford Gertz’s hypothesis that throughout history there have existed what he terms ‘theater states’, regimes in which the leaders do not base their power on providing security and prosperity but rather on providing continuous, ostentatious, participatory spectacles. The collective enterprise of producing massive public works and elaborately choreographed events is aimed at committing the regime’s subjects to the perpetual performance of roles within the grand theater of a fictional ideal society invented by the leadership. These roles, often compelled, but also willingly adopted, serve to give meaning to the lives of the people, and therefore help maintain the ruler’s power.

Perhaps, like the Kim family dynasty in North Korea, the survivors of the lost civilization instigated a ‘theater state’ system. This was a system which compelled or simply brainwashed people into working collectively towards the creation of spectacular structures and to engage in elaborate spectacles and ceremonies intended to embody and perpetuate the power of their leadership.

Isn’t this a plausible, if rather depressing, explanation of the lost civilization Hancock and his increasing number of gullible followers wants to believe in?

Actually, it just my opinion. A reflection of my gloomy taste. For all I know, the lost civilization really could have been Utopia.

Ryugyong Hotel, Pyongyang, North Korea, begun in 1987 but still remains unfinished. Another pyramid, but definitely not mentioned by Graham Hancock. Nor is it a warning about a future comet strike. At least, I don’t think so…..

NOTES

John Corvino is quoted from ‘The Philosophers’ Magazine’. https://philosophersmag.com/the-fact-opinion-distinction/

‘Continual Departures’

A photo of the first rose to bloom in my DMZ garden, and some thoughts it’s provoked about our mania for images.

A single rose, it’s every rose

and this one—the irreplaceable one,

the perfect one—a supple spoken word

framed by the text of things.

How could we ever speak without her

of what our hopes were,

and of the tender moments

in the continual departure.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Roses, No. VI. Translated from the French by David Need.

Here’s a picture of the first rose to bloom in my DMZ garden this year. It’s a species rose that’s native to Korea, China, and Mongolia called Rosa xanthina, aka the ‘Manchu Rose’. It’s unusual in several ways. First of all, it’s yellow, which is very rare in species roses, especially in occidental roses. It’s also unlike most species’ roses in being ‘semi-double’, that is, each flower has more than nine petals, although the flowers themselves are small – only about 5cm wide. It only blossoms once a year, in late April or early May. As this year it’s been unseasonably chilly and wet, it blossomed on May 1st. This makes it the very first rose – species or cultivar – to blossom. The Manchu Rose isn’t common. I was very surprised to find specimens for sale in a Seoul nursery. I’ve certainly never seen it growing wild. Last year my wife pruned it back too severely and it refused to flower. But this year it’s putting on a wonderful display.

Soon all the blooms will have gone. But as I’ve taken this photograph of the very first blossom, I’ve preserved it, and can share its beauty with you.

*

Tens of thousands of years ago, humans came up with the idea of making images. They chose to represent the animals with which they shared their environment, and by making images of them they effectively removed the animals from the flow of time and captured them. But this was obviously only an imaginary seizure. A fiction. It occurred in the mind and was externalized through a visual representation. The fact that the images were often painted on cave walls that were normally in complete darkness, so it was necessary to illuminate them with a torch or lamp, suggests that the cave itself was envisioned by these people as a metaphor for the mind within which images are fabricated. For them, learning to make images must have produced the consoling and confidence-building feeling that the mutable world had, in a certain sense, been taken into safe custody and controlled.

As a result, it seems certain that Upper Paleolithic humans greatly enhanced their feelings of self-efficacy, their belief in their ability to complete tasks and achieve goals. This was a level of control and domination that was impossible in the real world in which they were confronted with all manner of unforeseeable dangers and risks. But because of their limited knowledge and primitive tools the cave-painters could never lose sight of the obvious fact that the control they possessed through images was fictional, only a temporary reprieve from a real world that they knew was fundamentally uncontrollable.

They were acting out what the contemporary German sociologist Hartmut Rosa in his book The Uncontrollability of the World (2020) calls the ‘irresolvable tension between our efforts and desire to make things and events predictable, manageable, and controllable and our intuition or longing to simply let “life” happen, to listen to it and then respond to it spontaneously and creatively.’ (p. 60). In other words, human relationships to the world are torn between violence and aggression, on the one hand, because we are motivated by the will for mastery and control, and on the other, a more open and accepting attitude imbued with the desire for uncontrolled interplay with the world.

*

It only took about 35,000 years for us to make the journey from painting the walls of caves to taking digital photographs with smartphones of roses,. A camera allows us to make the world knowable, accessible, manageable and useful by turning it into an image. Thanks to the extraordinary developments associated with modernity, we have hugely increased our store of knowledge and technological capacity, and we have become very successful at exerting our dominance over the world.. But Rosa stresses that this sense of mastery has come at a very high price. Paradoxically, our very ability to impose such a high level of control has led to a way of life that is all too often characterized by profound alienation, one in which we are inwardly disconnected from other people and outwardly disconnected from the world.

In contrast to a life of alienation, Rosa describes our most cherished experiences as involving what he calls ‘resonance’: a responsive openness to being affected by the world, to being touched, moved, or ‘called’. When we have a resonant relationship to the world, it feels like an oasis. But when we are alienated, it becomes a desert. Any attempt to control a situation, an object, or a person, in the sense of making them knowable, accessible, manageable, and useful, will automatically destroy the possibility of having a resonant relationship with that particular portion of the world, and pushes us towards alienation.

The possibility of experiencing resonance depends on what kind of society we live in, what opportunities are given us to respond to the world, and for the world to ‘respond’ to our desirous approaches. We are constantly being offered visions of better, more resonant worlds, and we seek them out in situations ranging from love affairs, art galleries, favourite restaurants, and roses bloom in our gardens or public parks. But the potential for these situations to actually offer resonance are constantly being thwarted by our compulsion to take control of them. Our society is systemically driven to exert maximum control over the world.

A primary reason why we so avidly photograph seemingly almost everything these days is because we think the camera can help us experience resonance through increasing our control of the world. But in the very act of successfully ‘capturing’ the moment we risk ruining any chance of feeling its resonance. For in taking a photograph we substitute for the uncontrollably limitless real three-dimensional world of lived experience a controllable, fictional, miniaturized, two-dimensional world of the digital image. In the process we forget how to ‘simply let “life” happen’, choosing instead to inhabit a world in which we believe things and events are more or less totally predictable, manageable, and controllable.

The experience of resonance is like a fish in the fast-flowing river that eludes all our best efforts to grasp it and hold it in our hands. But we are increasingly reluctant to listen to the world and ‘respond to it spontaneously and creatively’. For what makes our time with roses ‘tender moments’, as Rilke puts it in his beautiful poem, is precisely the fact that we have accepted that we exist in a world characterized by ‘continual departure.’

Notes

David Need’s translations of Rilke’s ‘Roses’ was published by Horse and Buggy Press in 2018.

My book, ‘By Any Other Name. A Cultural History of the Rose’ was published by Oneworld Publishing in 2020.

Hartmut Rosa’s books are translated into English by Polity Press.

‘Flood the Zone with Shit and Howling’. Lessons from North Korea

Sometimes, I’m grateful to North Korea for helping me to see more clearly what’s happening in the world more generally. In this case, their ‘noise-bombing’ and balloon sending has helped me understand President Trump.

A balloon from North Korea carrying garbage and excrement lying in a South Korean rice field in the Spring of 2024.

These days, a deliberately unsettling medley of sounds are being blasted across the DMZ by North Korea. It’s what’s known as ‘noise bombing’, a nasty aural dimension of psychological warfare. The sounds mostly consist of deep apocalyptic droning, wailing sirens, and on occasion, screaming women and howling wolves. We can sometimes hear some of the sounds in our village - it depends how strong the wind is blowing from the north - but so far, I’ve only been able to detect the droning and sirens. South Korea sends its own ‘noise bombs’ towards the North - K-Pop music and other good news about living in a free country. Before, when the North noise-bombed the South they also used patriotic music and loud-speaker announcements about how their country is a workers’ paradise.

This new unsettling development signals a change in strategy in which the North no longer uses ‘noise-bombing’ as propaganda in the obvious sense. The change parallels another new strategy: sending helium balloons across the border which now are not filled with DPRK propaganda, as before, but with garbage and human and animal excrement. So far, none have come down near our village, so I have only seen them in the news media. This is ostensibly a response to actions originating in the South - balloons sent by North Korean defector groups and Christian organizations which contain propaganda. In fact, it’s an illegal activity in the South, but nevertheless continues to be a regular occurrence..

Both the howling and the shit are a reflection of Kim Jong-un’s declaration that North Korea’s goal is no longer a re-united Korea, and that the South is now an implacable enemy to be ultimately destroyed. This has, of course, been the truth since the Korean War, but until last year the North persisted in maintaining the fiction of reunification as an inclusive aspect of their much bigger fiction – that of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as a whole. This fiction included the assumption that the people in the Republic of Korea were oppressed and just waiting to be liberated by the North. Now the North has re-written or erased part of the official narrative, evidently because it no longer serves any practical purpose, and can be discarded without threatening the status quo in the North. as I noted in my previous post, there are obvious reasons for the change in relationship. Almost no one in the North is old enough to remember when there was just one Korea, and who perhaps have relatives living in the South. The new leadership under Kim Jong-un is much too young to know anything except two Koreas, and have no sentimental attachment to the South. But I also think something more momentous is going on.

*

Communication theorists refer to what they term ‘information noise’: an external input into a communication channel between a sender and a receiver that potentially obscures or makes incomprehensible the signal,or the message. In other words, an increase in ‘noise’ results in a decrease in determinable meaning. There are various categories of such ‘noise’. The North Korean variety in the ‘noise bombing’ is ‘physical noise’, that is, a disturbance or interference coming from an external source that obscures or obstructs the signal. In the case of the balloons, it’s ‘semantic noise’, an interference in the common background or knowledge that makes sharing ideas possible..

But North Korea has weaponized this ‘physical’ and ‘semantic noise’, and by so doing turned it into a kind of information. Paradoxically, the very targeted noisiness of the ‘noise’ becomes a message. It signals that North Korea now assumes there is the total absence of a shared, common cultural background or store of knowledge, and so it is impossible and pointless to freight ‘noise bombing’ with any information in the form of communicable ideas.

The North consciously intends through their latest aggression to show what they think of the South’s propaganda efforts, and to announce the fact that North Korea has given up trying to communicate a message that the receivers, South Koreans, can understand.. However, I think one can argue that unconsciously the North is finally telling us the truth about their own regime. The shit and howling says quite a lot about the sender, because they an inverted expression of what life is really like in North Korea, a nation where communication is effectively entirely devoid of ‘noise’. Everything is organized so that on all levels – physical, physiological, psychological, semantic, cultural, technical, and organizational – the regime can optimally deliver a pure message without ‘noise.’ This is another way of saying that North Korea is a totalitarian state. In a democratic society there is always bound to be ‘noise’ in any communication, especially in a multi-cultural society with multiple senders of messages - a Babel magnified infinitely by the Internet.

*

Sometimes, I’m grateful to North Korea for helping me to see more clearly what’s happening in the world more generally. In this case, their ‘noise-bombing’ and balloon sending has helped me understand President Trump. During his first presidency, Steve Bannon famously coined the motto ‘flood the zone with shit.’ Well, North Korea have inadvertently taken his advice. They are trying to flood the Demilitarized Zone with ‘shit’ – quite literally in some instances. For Bannon was advocating a strategy of maximum communication ‘noise’. You create so much of it that the real messages are rarely received.

So, what is the real message? It looks more and more likely that the real message refer to a coming coup d’etat. The ‘noise’ makes it possible for the coup to happen in slow-motion, so to speak. Without the usual violence, the messiness of storming the Capitol. When will freedom-loving Americans wake up to this increasingly obvious fact? I certainly hope they don’t copy the Germans after they elected Hitler in 1933.

NOTES

The image is a screenshot from:

https://www.euronews.com/2024/10/24/north-korean-balloon-dumps-rubbish-on-south-korean-presidential-compound-a-second-time

For more on ‘information theory’ see: https://www.soundproofcow.com/4-types-of-noise-in-communication/?srsltid=AfmBOorXhkA_oW2-HHLfmkLeVIe-iBH5uXlu6qjjjqfJxbkmyDQDZgEF

https://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1066_Communcation_Theory.pdf

Martial Law in South Korea (Cancelled)!

It’s Christmas Day. A lovely white Christmas, here in South Korea. For one reason or another, I haven’t written any blog entries since the summer. But today, I feel compelled to comment on the recent drama here in the Republic of Korea. I refer to President Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law declaration on 3rd December, which turned out to be the shortest period of martial law in history, as it was cancelled the next day.

It’s Christmas Day. A lovely white Christmas here in South Korea. From up there, where I took this photo, you can just see what must be, bar a few utterly failed states in Africa, the worst country on Earth: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. They’ll be no Christmas Day over there. Just more misery.

For one reason or another, I haven’t written any blog entries since the summer. Mostly, this is because I’ve been busy working on two new book projects and making art in my wonderful new studio. I’ll write more about these soon.

But I feel compelled to comment on the recent drama here in the Republic of Korea. I refer to President Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law declaration on 3rd December, which turned out to be the shortest period of martial law in history, as it was cancelled the next day. But it’s certainly been a wake-up call about how vulnerable democracy is, but also how robustly it can protect itself.

*

Martial law officially involves the armed forces stepping in when civilian authorities have stopped functioning, as in the case of war, insurrection, or natural disaster. In democracies it is usually used in times of war, or in relation to a specific threat or crisis within the nation, in which case it’s not imposed across unilaterally. But the ROK’s relationship with martial law is unique, in that the nation was founded in 1948 under martial law due to the communist threat both from the DPRK and from within the ROK itself. Then the Korean War began, lasting from 1950 to 1953. In May 1961 there was an army coup, which brought General Park Chung-hee to power and began another long period of martial law. When Park was assassinated in 1979, a brief moment of non-military rule began, but this was stamped out that same year by the military, and another eight year period of martial law began, including the brutal suppression of the Gwangju uprising in 1980. In 1988 the first democratically elected President of the ROK was Roh Tae-woon heralded a period in which, until the 3rd December, there has never been martial law. A lot has changed in the republic of Korea since the 1980s, but this seems to have been missed by President Yoon.

The most important difference is that the ROK is now a working democracy. Another is that it is a powerful world economy. And another is that despite the threats of the DPRK, including nuclear threats, the two Korea’s are now living in totally unequal worlds, a situation that’s been acknowledged by the DPRK leadership’s decision to stop pretending they want a re-unified Korean peninsula. They recently even blew up on their side the roads that traverse the DMZ., effectively announcing their status as a prison-nation. Kim has also sent a large quantity of munitions to Russia, and several thousand of his elite forces are currently being put in the meat grinder in Ukraine. The DPRK is therefore as unlikely now to invade the South as at any time.

*

Here are some choicer extracts from President Yoon’s statement announcing martial law.

He begins by accusing his rivals, the Democratic Party, of the very thing he is about to attempt:

This is a clear anti-state act of conspiring to incite rebellion by trampling on the constitutional order of the free Republic of Korea and disrupting legitimate state institutions established by the Constitution and the law.

The lives of the people are of no concern, and state affairs are in a paralyzed state solely due to impeachments, special prosecutors, and the opposition party leader's shield (against prosecution).

Now, it’s true that Yoon has been a lame duck President for some time because his party lost out big time in local elections, and the winning Democratic Party has been blocking more or less all Yoon’s attempts at legislative reform. His wife is being investigated for accepting expensive gifts (bribes), and his popularity has plummeted. Yoon must have felt very frustrated. But this is hardly grounds for martial law. Therefore, like the military rulers of the pre-democratic Republic, Yoon sought to justify his actions by evoking the imminent threat from the DPRK:

Dear fellow citizens, I am declaring a state of emergency martial law to protect the free Republic of Korea from the threats of the North Korean communist forces, to eradicate the shameless pro-North anti-state forces that plunder the freedom and happiness of our people and to safeguard the free constitutional order.

And here’s the best bit of all, from towards the end of Yoon’s short statement:

Due to the declaration of martial law, there may be some inconveniences for the good citizens who have believed in and followed the constitutional values of a free democracy, but we will strive to minimize such inconveniences.

‘Inconveniences’! ‘Strive to minimize such inconveniences’! Yoon’s low assessment of the South Korean people is summed up here. Did he really believe they would only experience martial law as an ‘inconvenience’, as if it was nothing more than roadworks slowing down their commute home? What was in Yoon’s deluded mind? He seems to have lost touch with reality, or perhaps its more accurate to say reality got funneled into a very narrow space full of his petty political problems. He lost any sense of the Big Picture.

In the end, I felt very proud of the South Korean people, and most particularly of the army, whose top brass showed themselves to be far more wedded to democracy than the President and his cronies. Huge numbers of South Koreans rallied to democracy and sent the scoundrel packing. Unfortunately, Yoon is still at large. But not for much longer. Several Presidents (5, including the President and former general who led the 1979 coup, Chun Doo-hwan) have been impeached and/or given prison sentences, including death sentences. But all - except Roh Moo-hyun (President from 2003 -2008) who committed suicide - received pardons. Yoon Suk-yeol will therefore in all likelihood soon be the sixth ROK President to go to prison, and maybe will even be given the death penalty if he is found guilty of treason. But history suggests he will also be pardoned.

*

I was also struck by the timing of Yoon’s declaration of martial law, which was almost exactly one month after Trump was elected President (5th November). I can imagine that Trump will try the martial law card in the US in the not too distant future if it seems necessary. In fact, federal and state governments in the USA have declared martial law over 60 times during its history – for example, after Pearl Harbor in 1942 and until the end of World War Two. The last time was limited to a single town in Maryland during in 1963 Civil Rights Movement crisis.

What Yoon’s action exposes is the influence of the trend towards populist and authoritarian leaders which is undermining democracy and emboldening half-baked wannabees like Yoon to accelerate the process. In the case of the ROK, he totally underestimated the sound commitment of his country to democratic government of the kind that has checks and balances put in place to make sure no one person can try to do what Yoon did. He also underestimated the sea change in the minds of South Korea’s military leaders, who refused to be employed as his bully boys.

But I’m wondering if the Constitution of the United States, which is famously buttressed by such checks and balances, is going to be able to take the strain of another Trump Presidency. The US seems so utterly ravaged. To borrow Ezra Pound’s words, it’s almost beginning to look like the US is a ‘botched civilization’.

*

Here’s a glimpse of one of my new ‘LP Paintings’, in which I make monochrome paintings based on the covers of LP’s, preserving only the original typography of the title and artist. In this case, its an LP by Bob Dylan. The title seems timely. I liked the way the sunlight in my studio played over its surface, so I turned it into a New Year’ card.

Kim Guiline. Introduction to a Dansaekhwa Artist

I recently wrote the catalogue essay for the current solo exhibition of the Korean Dansaekhwa artist Kim Guiline at Hyundai Gallery in Seoul (until July 14). This is a version of part of the essay, in which I introduce Kim’s highly distinctive painting style..

Installation view of the exhibition Kim Guiline. Undeclared Fields at Hyundai Gallery, Seoul.

I recently wrote the catalogue essay for the current solo exhibition of the Korean artist Kim Guiline at Hyundai Gallery in Seoul (until July 14). Here is a version of part of the essay, in which I introduce Kim’s highly distinctive painting style.

*

The Korean artist Kim Guiline was born in 1936 when Korea was a Japanese colony and in what became the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea. Aged twelve, escaped south shortly before the Korean War broke out. Initially, Kim studied French literature as an undergraduate in Seoul, and in 1961 he moved to Dijon in France to continue his studies with the intention of becoming a writer or poet. But he soon abandoned this goal and switched to Art History, before deciding to become a painter. In then studied art at the Beaux-Arts in Paris, going on to graduate from the École Nationale des Art Decoratifs. Kim opted to live in Paris for the rest of his life and he only returned to Korea for short visits. He died in Paris in 2021. Nowadays, Kim associated with Korean Dansaekhwa (monochrome painting), and artists such as Park Seo-Bo, Chung Sang-Hwa, Yun Hyong-Keun, and Lee Ufan..

Changes in the viewing position adopted by us, the beholders, in relation to a typical painting by Kim radically changes what we see. From a distance, we perceive usually only a monochromatically colored rectangle, but as we move in closer we begin to make out rows of painted dots organized within rectangular zones that run parallel to the edges of the painting. At this position Kim’s paintings seem to become animated by the rhythm of these dots as we scan them across the surface. Close up, we see that the dots are slightly raised above the surface, which introduces a tactile dimension. Kim invites an active role for the body, one in which changes occur to cognitive readings via perceptual ones. Kim foregrounds the fact that a painting is an object that is not just seen head-on and in an isolated context (which is how we view an photographic reproduction like the ones in this catalog) but in real space is encountered from different angles and distances, and in the context of other paintings. These variously adopted viewing distances, performed in time, determine the relative authority of what is seen. In this sense, his work is relational and ‘viewer-activated.’

In the basic visual format adopted by Kim from the late 1970s until his death, the surface of the canvas or sheet of paper is divided with bilateral symmetry into rectangular sections. In works from the late 1970s and early 1980s a barely discernible drawn grid structure peeks through the coatings of the single color of paint with which he covered his work. As Kim’s work developed, he suppressed the visual evidence of this structuring linear grid, while he still retained it as an underlying regulating architecture. This structure is filled with rows of seed-like dots, about the size of a fingerprint, which Kim systematically painted within the rectangular areas. As time went by, and the grid lines disappeared, the dots sometimes take on slightly syncopated alignments, but they still essentially hold to the underlying gridded format. These serial dots are also built up into relief, producing a tactile dimension. This, like the rectangles which are aligned parallel to the edges of the canvas, counter any tendency to read spatial illusion into Kim’s paintings - for example, to see them as windows or doorways - and encourages the perception of his paintings as literal objects with two-dimensional surfaces.

Inside, Outside, 1987–1988, oil on canvas, 240 x 160 cm.

Inside, Outside, 1987, oil on canvas, 200 x 250 cm

The element of raised relief in the dots introduces a level of haptic engagement that involves making a link between the eye and the hand through engaging two bodily functions: the tactile and the kinesthetic. The former brings direct physical contact, providing information about location, surface, vibration, and temperature. The accumulation of knowledge gained through touch is slower than that gained through visual perception, but it is more difficult to deceive. Touch confirms and demystifies. The kinesthetic, meanwhile, is involved with knowledge about position, orientation, and force. The haptic brings into play greater awareness of body movements, of stimuli relating to bodily position, posture, and equilibrium that come from more immersive engagement. It helps build a stronger and more authentic awareness of a three dimensional and temporal world than the sense of sight. While vision facilitates a general conceptual knowledge through offering spatial detachment from what is perceived, and is therefore essential for the success of writing, touch verifies and brings conviction by providing specific knowledge revealed intimately through close contact. While a predominantly retinal response to the world necessitates viewing the surface of a work of art from a certain distance, with tactile perception viewing at close range is necessary

Inside, Outside, 1985–1986, oil on canvas, 240 x 160 cm

The tactile dimension is also enhanced by the fact that Kim nearly always reduces his paintings to an all-over single colour which covers both the surface ‘ground’ and the dot ‘figures’ with the same hue. He applied multiple thin layers of a single oil colour to his canvas surfaces so as to produce a thick, mat, coating that is not flatly uniform but rather has a skin-like translucency. This monochromatic effect removes a salient visual sensation provided by the relationship normally set up between different colours within painted composition. As the painted dots and the background colour are more or less the same, the former are never clearly visually distinguishable from the ground, as they would be in conventional painting and writing spaces. But the use of monochrome could have significance well beyond simply the desire to enhance the material aspect of painting. As the visual dimension of light, colour is intrinsically shifting, a property produced by the retina rather than objects, which generates a pulsing, undulating sense of space. In being both material and sensual, color engenders visual pleasure and resists full incorporation into a code or sign-system. Colour is more subjective than line, playing on the emotions, and its opposition to form, and unstable relationship to coded systems, have made color a favoured vehicle for the artistic exploration of what cannot, or cannot yet, be encoded.

Inside, Outside, 2004, oil on canvas, 55 x 145 cm.

In both the west and in the literati scholar culture of East Asia, colour was traditionally deemed to be of less value than line, because of its sensuous indeterminacy. Modern western artists, however, initiated an exploration of the visual experience of luminous chromatic fields painted in oil, inviting a range of new responses and interpretations. Monochrome painting became a potential space within which to project emotions and imaginative scenarios, associations spanning extremes of human consciousness from despair to transcendence.

As Thomas McEvilley wrote: “throughout the twentieth century the broad one-colour field has functioned both as a symbol for the ground of being and as an invitation to be united with that ground”. In Kim’s case, the monochrome allowed him to encourage the perception of a painting as a simple unity. But formalist or metaphysical readings of this space are too limiting, and also limit Kim’s work to a western aesthetic framework.. To my mind, Kim’s paintings explore the concealed but close and evocative alliance between the codes associated with ‘painting space’ and ‘writing space.’ His paintings insinuate into pictorial space the idea of a text inscribed on a page or some kind of vertically oriented monument or memorial. But Kim doesn’t communicate anything like a clear linguistic message. His paintings obviously cannot be decoded or ‘read’ in a conventional sense. The dots are not words. They do not comprise legible sentences. Nor are they visual symbols. They are more like pure indexes of the sustained presence and methodical and intentional actions of the artist. Kim foregrounds the fact that, as Roland Barthes wrote, poetic writing is "a field of action, the definition of, and hope for, a possibility.”

The elusive in-between space Kim Guiline creates reflects a consciousness inevitably involved in language, in segregations and the desire for control, but also one that is embodied and strove to undo difference and make intimate connections within a holistically experienced world. Kim’s aimed not to produce stable form but to serve as a conduit and go-between through which the essential energy pervading the world could be alluded to. He sited his work between the spaces of painting and writing, and organized it to allude to a powerful but undeclared message redolent with the desire for the experience of timeless immersive equilibrium in the ever-changing world. Ultimately, Kim, a Korean in self-imposed exile in Paris, hoped to overcome in his work the alienation caused by the misunderstandings and prejudices that are an inevitable consequence of living in a language infested ‘Tower of Babel’. Through his painting, he strove to reconnect with a more primordial experience of language, or of ‘writing’ As he himself declared, for him goal was always “the essence using nothing but accurate words.”

The catalogue, which includes my essay, ‘Kim Guiline. Undeclared Messages’.

NOTES.

See my book The Simple Truth. The Monochrome in Modern Art (London: Reaktion Books, 2020). Translated into Korean as 모노크롬, translated by Hee-kyung Hwang, Yeon-sim Jeong, supervised by Bu-kyung Son (Seoul: Ahn Graphics, 2020).

Thomas McEvilley is quoted from ‘Seeking the Primal in Paint: The Monochrome Icon’, in G. Roger Denson ed. Capacity: History, the World and the Self in Contemporary Art and Criticism, (Amsterdam: OPA, 1996) page 87.

Roland Barthes is quoted from Writing Degree Zero [1953], trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith (New York: Beacon Press, 1970), page 9.

All images courtesy of Hyundai Gallery website.

Roses, 2024!

As a rose lover and the author of a cultural history of the rose, I can’t pass through the months of May and June without doing a post about roses and sharing with you some photographs of rose blossoms…..And some poetry by John Keats.

As a rose lover and the author of a cultural history of the rose, I can’t pass through the months of May and June without doing a post about roses and sharing with you some photographs of rose blossoms.

A couple of weeks ago I visited the lovely Greenhill Rose Garden, the flagship garden of the Korea Rose Society’s in Gwangju, south-east of Seoul. Here are some pictures upon which to feast your eyes:

This is called ‘Tea Clipper’, an example of one of the so-called ‘English Roses’ created by David Austin, which aim to blend the look and scent of old-style roses with the hardiness and repeat-blooming characteristics of the new. Below a detail. It is delicately perfumed.

This is ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ a variety bred by the prestigious French rose breeders Meilland.

Another David Austin shrub rose: ‘Lichfield Angel’.

The Korea Rose society also created their own rose in 2019 to celebrate the visit of the President of the World Federation of Rose Societies and in memory of the Founding President.

The garden also features some of the classic old roses. Here, above, is ‘Complicata’ a Gallica rose, and an example of a variety created from one of the first species roses to be cultivated in Europe. And below is ‘William Lobb’, the ‘Old Velvet Moss Rose’, first bred in France in 1855. It is deliciously sweetly fragranced. Note how thorny it is!

The garden is the creation of the President of the Korea Rose Society, Kim Wook-Kyun. He also kindly contributed his expertise by overseeing the translation of my book, By Any Other Name. A Cultural History of the Rose into Korean. It was published by Ahn Graphics in 2021:

As I write this post on 9 June the roses in my garden have already bloomed magnificently and their petals have mostly fallen. But thanks to the assiduous attention of modern rose breeders like Meilland and David Austin, the varieties I cultivate should all blossom again before wintertime.

*

And finally, a poem by the English poet John Keats which I didn’t have a chance to present in full in my book, entitled ‘To a Friend who sent me some Roses’:

“As late I rambled in the happy fields,

What time the sky-lark shakes the tremulous dew

From his lush clover covert; - when anew

Adventurous knights take up their dinted shields:

I saw the sweetest flower which nature yields,

A fresh-blown musk-rose; ‘twas the first that threw

Its sweets upon the summer: graceful it grew

As is the wand that queen Tatania wields.

And, as I feasted on its fragrancy,

I thought the garden-rose it far excell’d:

But when, O Wells! thy roses came to me

My sense with their deliciousness was spell’d:

Soft voices had they, that with tender plea

Whisper’d of peace, and truth, and friendliness unquell’d.”

Keats refers to the species rose Rosa moschata, the Musk rose. Prior to 1500, it was the most powerful fragranced rose in Western Europe. The pinkish-white flowers grow in clusters, and their semi-double petals are more closed than single petalled wild roses. The Musk blossoms in late summer and into early autumn, and so it is also known as the ‘Autumn Rose’. Experts believe it originated in Persia, although some sources argue for even farther afield in India or China. It probably came to northern Europe via Spain, and only arrived in England in the early sixteenth century. Here is Redouté’s painting of the Musk rose:

But Keats has surely gotten his roses mixed up. He refers to his Musk as being ‘the first that threw Its sweets upon the summer’, whereas the Musk is actually a late bloomer. In fact, he was evoking some famous lines from Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, a supposition confirmed by the reference to Titania. Shakespeare wrote:

I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,

Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows,

Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine,

With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine:

There sleeps Titania sometime of the night,

Lull’d in these flowers with dances and delight

This then, is a fine example of what scholars call intertextual allusion. Also an example of art replacing, or at least overlaying, lived experience - and botanical accuracy.

NOTE

For more on roses see: https://www.simonmorley-blog.com/blog-1/roses

The Redouté painting is sourced from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_moschata#/media/File:Rosa_moschata.jpg

Sowing Rice

The rice is being sown in the fields around us. Some thoughts on the rice field as metaphor in relaation to Korean art.

This is the season when the farmers here in Korea plant their rice. First, the terraced fields are ploughed over by a tractor. Then, an irrigation system begins filling the fields with water, so they look like rectangular ponds. Like this:

Meanwhile, a field has been set aside as a ‘nursery’ for growing the rice shoots en masse:

As I write this blog, these shoots are being replanted in the nearby fields:

A specially designed tractor is employed with very thin wheels and a rotary feed system that precisely sows the rice bushels in neat rows. The work that once would have taken a whole village several days is now quite easily and rapidly achieved. Which is just as well, because young Koreans don’t want to be farmers anymore, and foreign labour is increasingly employed.

The Korean peninsula, which is over 70 percent mountains, is not an ideal landscape to grow rice.. Nevertheless rice - ‘Bap’ - is ingrained within the daily life and culture of Korea. It plays a key role in ceremonies and celebrations., such as at Chuseok, when a bowl of rice is traditionally left as an offering on an ancestor’s grave. Korean cuisine is built around rice, which has been a culinary staple since the Neolithic period. Koreanc will eat rice for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. This rice is different from other varieties in Southeast Asia, in that it is shorter grained and very sticky. It is also mild in flavor. At home, we have a rice maker called a Cuckoo which is programmed to speak and always makes perfect cooked rice:

Our Cuckoo rice maker. It talks!

*

Watching the rice planting process going on in the fields around here has made me think once again about a metaphor that has seemed relevant in understanding a basic difference between Western and Eastern art traditions. In an essay I wrote about Chung Sang-Hwa (1932 -) for the catalog of his 2022 Retrospective at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, I suggested that Chung’s painting invite analogies related to agriculture. He ‘farms’ his surface:

Chung Sang-Hwa, Untitled 91-12-7, 1991, acrylic on canvas, 259.1 X 193.9cm. Courtesy Hyundai Gallery.

This metaphor also extends to another Korean artist I have just finished writing an essay about for a forthcoming exhibition at Hyundai Gallery in Seoul: Kim Guiline (1936 - 2021). I will do a post on Kim’ work specifically in the near future, but for now I want to suggest that here too, an analogy to farming is pertinent. This is an example of a typical work:

Kim Guiline, Inside, Outside, 1983, oil on canvas, 250 x 200 cm. Courtesy Hyundai Gallery

I don’t just mean that, literally, Chung and Kim’s surfaces visually bring to mind the straight rows of recently planted rice or the stubble intentionally left in a field after the harvest. The metaphor goes deeper than simply appearance. Unlike Western artists who work their surfaces vertically, Chung and Kim both continue to work on theirs horizontally, as was traditionally the way before the impact of Western art was felt. In fact, one could argue (and here I am borrowing an insight of the art historian John Onians) that the characteristic posture of the European artist from the sixteenth century onward, in which the artist stands before an easel - known in Italian as a cavaletto and in french as a chavalet – a ‘horse’ – holding a brush in one hand and a palette in the other, conjures chivalric and military metaphors of the knight brandishing a sword and shield.

Onians suggest that this reflects at an unconscious level the new assertiveness and authority possessed by the artist in the Renaissance. But it could also go deeper than that and reflect a basic attitude to the world for the European artist in which the subject of representation is subdued by force - is ‘possessed’ or ‘captured’. This relationship of violent mastery was also deepened as artists became urbanized and Europe industrialized, and the world of art was progressively distanced from the world of cultivating the land..

By contrast, in the Eastern artistic tradition such violence at the heart of art is absent. The artist sat on the floor above the surface upon which they plant their marks, and a world is not being subdued but rather cultivated. In so far as Korean artists of Chung and Kim’s generation grew up in a country that was predominantly agricultural, the use of such an agrarian metaphor for the practice of art seems a viable association even in the period of modern art. Both Chung and Kim aim at what could be called ‘harmonious regulation’. The surface of their paintings is for them understood as a field that yields without exhausting its potential as part of a continuous cycle in which the artist’s movements correspond with those of their materials. A painting surface is a zone between the earth below and the atmosphere above, where the two intermingle as part of a process instigated by the artist. So one could say that these artists’ surfaces are analogous to agricultural fields in the sense that they are places of planting, where the traces of systematic movement are sown.

NOTE

John Onians observations can be found in his book European Art: A Neuroarthistory (Yale University Press, 2016)

Blue jeans are still subversive (if you live in North Korea)!

More zany news from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Blue jeans are still subversive! Recent evidence of this is the censoring of a British television series about gardening that’s been pirated by the North Koreans to show on state television.

More zany news from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Blue jeans are still subversive over there! Recent evidence of this is the censoring of a British television series about gardening that’s been pirated by the North Koreans to show on state television. The host of ‘Garden Secrets’ is Alan Titchmarsh, who is something of a household name in the UK, and definitely harmless in every way. But when he’s seen wearing jeans, the DPRK censors do that bizarre digital blurring-out effect. This is what it looks like:

For a while a few weeks ago, the BBC had fun reporting the absurdity of this procedure. As the news item put it: “Jeans are seen as a symbol of western imperialism in the secretive state and as such are banned.” Alan Titchmarsh was on record as saying: "It's taken me to reach the age of 74 to be regarded in the same sort of breath as Elvis Presley, Tom Jones, Rod Stewart. You know, wearing trousers that are generally considered by those of us of a sensitive disposition to be rather too tight".

The subliminal message behind the story is clear: those North Koreans are definitely deranged and we (the Brits) are not. In fact, one of the perennial cultural roles of ‘exotic’ places located beyond the British Isles, especially those very far beyond, is to serve as sources of amusement and self-satisfaction for us Brits. The underlying message is usually that the only people with any common sense are us. Elsewhere, people are want to believe in the most silly nonsense, and to behave in ways that are perverse, indecent, childish, dangerous, etc. etc. In this way, the British status quo gets normalized as what’s ‘normal.’ As the public announcement says these days on the UK’s public transport system: ‘If you see something that doesn’t look right, call xxxxxx. See it. Say it. Sorted.’ Evidently, we are all supposed to automatically and unequivocally know what looks ‘right’ is. But how? Because we are habituated to a certain way of thinking and doing things. And for that to be possible, we need to be reminded regularly of the extra-ordinary. Which is where foreigners come in handy.

*

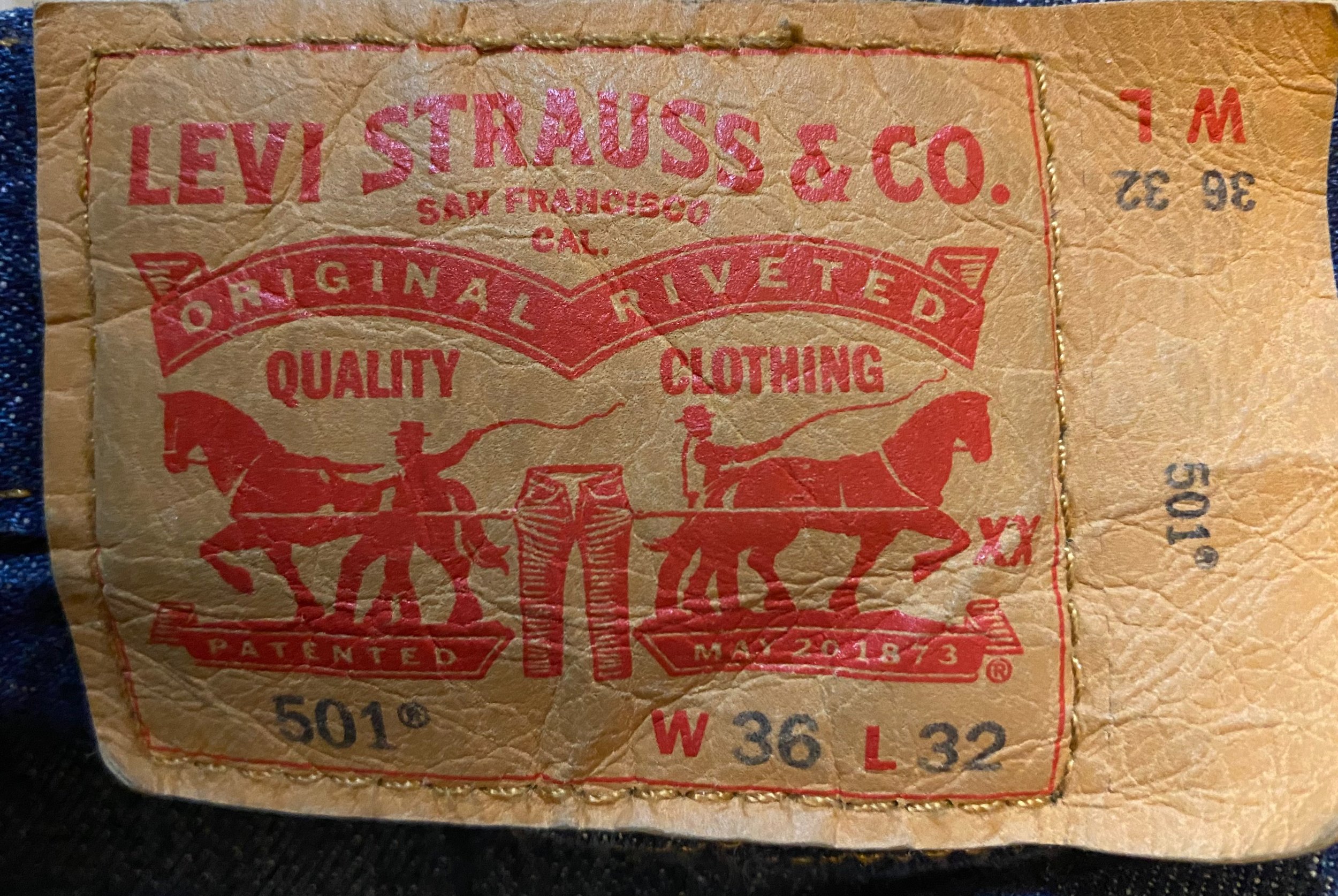

As you almost certainly know, denim jeans were designed in the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States as work wear. The inventor is usually credited as the German immigrant Levi Strauss, who moved to San Francisco during the ‘gold rush’ and patented the innovative design feature of riveted denim in 1873.

By the time I was ready to wear jeans in the late 1960s there were basically three brands on offer: Levis, Wrangler, and Lee, which were all American. As I became fashion conscious in my late teens in the mid-seventies, I decided for some reason (maybe it was something to do with Jack Kerouac and the Beats) that I could only wear Levi 501’s, the original, button fly, shrink-to-fit design (zippers were a standard feature by the mid-1950s). But there was nowhere in my hometown that sold these classic jeans, and so I would make a pilgrimage to nearby Brighton, where there was one shop that reliably stocked them. Once back home, I’d put the cherished (and rather expensive) item on, then lie in the bath watching the indigo dye turn the water blue as the jeans molded themselves nicely to the form of my lower torso and legs (or that was the goal, anyway).

And as they did, it was as if by an act of magical anointing I became part of the great success story. I became part of the American Dream. For while jeans are certainly cheap, comfortable, and hard-wearing, much more was being worn by my younger self than just blue cotton denim. By this time, jeans were a very powerful cultural signifier. What had started out in the west and mid-west of America as hardy workwear for cowboys, lumberjacks, farmers, and construction workers, by mid-twentieth century had morphed into a style icon sought by the young throughout the ‘free’ world. Like Coca-Cola, hamburgers and hotdogs, pop music, and rebellious and sexy youth, jeans came to represent a freer, happier way of life based on the American Dream.

First of all, American GI’s on service overseas – in Germany and during the Korean War and the Vietnam War in the East – wore them on leave, and they became a potent symbol of the new causal look of the Pax Americana. But at the same time, 1950s movies starring Marlon Brando and James Dean made jeans look attractively rebellious, and on Marilyn Monroe they looked sexy. So, jeans became increasingly a symbol of youth rebellion and anti-establishment attitudes. Many US schools in this period banned jeans from being worn by students. By the sixities jeans were what pop stars wore, and anti-Vietnam War protesters, and they were established as one of the most recognizable signifiers of non-conformity, if not of outright depravity. When I put on my blue Levi 501’s, aged sixteen in the provincial England of the mid-1970s, I was unconsciously identifying with the dominant version of ‘success’ within my society.

By the late 1980s you could buy ridiculously expensive ‘designer jeans’. This demonstrates how a symbol of rebellion gets easily co-opted or recuperated by what erstwhile rebellious young people even today (the West, anyway) call ‘the System.’ Jeans where you and I come from are definitely not any danger to civic order. Who knows what brand Alan Titchmarsh was wearing when he shot his gardening series. I bet they weren’t Levi 501’s. Then again, maybe they were…

My mum didn’t like blues jeans, either. I mean, back in the sixities and early seventies she didn’t like me to wear them. We lived in a suburb of a small seaside town, and she insisted I didn’t wear jeans when venturing into the centre of town. But eventually she bowed to the heady winds of cultural change that blew through the early 1970s and gave up on the dress restrictions. I never ever, ever thought I’d be able to draw a straight line between my mum’s sartorial code from back then and those of the DPRK today. But this yet more tragic proof that the DPRK is trapped in a time warp. Its animus against blue jeans belongs to the cultural values of the 1950s, not the present day. It quite simply hasn’t been able to progress beyond an ideological construct from the beginning of the Cold War.

But the DPRK is not alone. What the others so-called ‘rogue’ nations - Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan - have in common with the DPRK is precisely the refusal to westernize, to fail to swim with the seemingly inexorable tide of neoliberal global culturalism. To fall for the ‘American Dream” which has been exported to the ‘free’ world.

It’s worth spending a little time to consider just what this ‘dream’ is (or was). One on-line dictionary says it is “the ideal by which equality of opportunity is available to any American, allowing the highest aspirations and goals to be achieved.” But that seems a bit evasive. The website ‘Investopedia’ cuts to the economic chase: “The American Dream is the belief that anyone can attain their own version of success in a society where upward mobility is possible for everyone.”

But that’s narrowing things too much. From an artistic perspective, the American Dream means success equated with reward for the pursuit of extreme freedom of self-expression, willingness to shock and offend, and to push creativity continuously towards the ‘new’. In fact, these radical values were already part of the modern ‘Western European Dream’, but they were embraced and enhanced when they migrated to the ‘New World’, along with the useful additional assets of economic, military, and political power. Which makes one wonder: just what is ‘success’?

A more critical perspective is need. How about one applying a Marxist interpretation? Here’s something I found on the Internet: “When viewed through the lens of Marxism, the ‘American Dream’ is now more accurately described as a widespread fallacy than a meaningful goal to strive toward.” This quote comes from a very interesting source: a text written in 2023 by a pair of Iraqi academics in the course of writing a critique of Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’ (1949). This play is generally recognized as a searing indictment of the narrowly materialistic version of the ‘you-can-make-it’ ethos of the ‘American Dream’. (Just in passing, recall that, improbably, this same Arthur Miller was married to Marilyn Monroe, which means he could admire her figure in denim jeans at his leisure) The Iraqi academics, Ali Khalaf Othman and Fuad Sahu Khalaf, conclude: