Reflections on a photograph of a painting by Lee Ufan

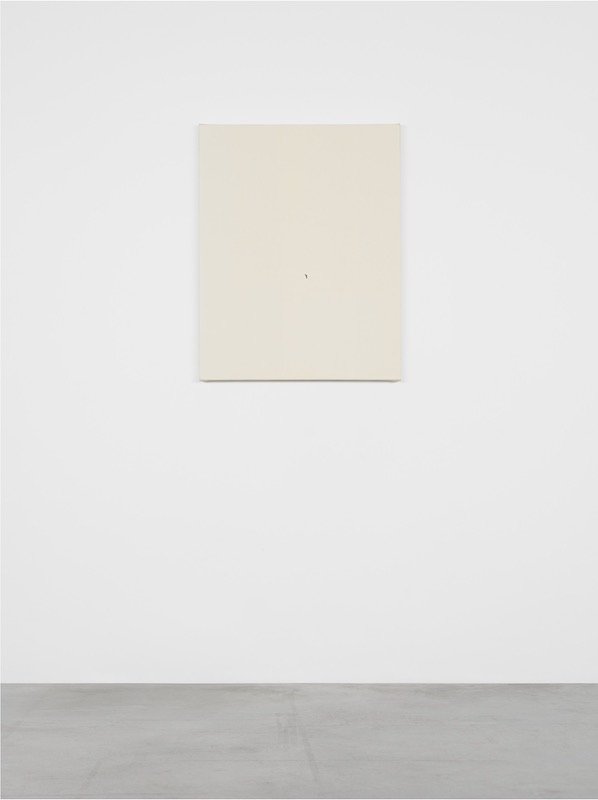

Lee Ufan. Dialogue. 2014. Oil on canvas. 93 x 73 x 4cm. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

I recently participated in a symposium at Art Sonje Center in Seoul on the theme of ‘Painting in the Age of Digital Reproduction’. The symposium was part of a broader UK-Korea academic research project in which I’m involved which explores the materiality of painting - especially minimal ‘abstract’ painting - in a age dominated by digital reproductions. This is particularly interesting to me because of the paintings I make, like my ‘Book Paintings’, such as this recent one, based on the first edition of Freud’s ‘Future of an Illusion’:

Simon Morley, 'Freud.'Die Zukunft einer Illusion' (1928)', 2022, acrylic on canvas, 45 x 38cm.

As you can see, the painting is not easy to photograph! In fact, this inadequacy is intentional, because I want my paintings to be more about the intimate and tactile than the public and visual. Instead of a strong contrast between the text and the surface - as in the original book cover on which the painting is based - the colour is uniform and the contrast between text and surface is produced through small tonal difference and difference in texture.

Here is a version of part of the talk I gave in the symposium in which I discussed a painting by Lee Ufan, Dialogue(2014), which is illustrated at the start of this post. This painting featured in an exhibition we staged recently as part of the research project in London at the Korea Cultural Centre, called Transfer, in which a selection of Korean and British abstract paintings (including mine) were juxtaposed with video documents of the paintings. The digital ‘documents’ were specifically intended to avoid the obvious, ‘default’, kind of document which is a digital photograph like the of the Lee Ufan painting or mine shown above. The Lee painting is clearly very minimal indeed, and so it is all the more challenging to document photographically. Here it is as installed in the exhibition Transfer, alongside the video by the Belgian video and performance artist Rafaël, which was made as a decidedly unorthodox ‘document’ of the painting (more on the video below):

*

A popular abbreviation online these days is ‘IRL’ – ‘In Real Life’ – which is used to distinguish between a relationship in the digital realm and one in the analogue, ‘off-line’, world. As more and more people spend their time online or on their smartphones, it is becoming an increasingly significant task to consider the differences between the former and the latter. For while ICT (Information and Communication Technology) provides unprecedented possibilities for recording, copying, transferring, and disseminating data, and has far reaching and positive social implications, there are also obvious dangers. What interests me here is the fact that, as the philosopher Richard Kearney puts it in his book Touch, due to the digital revolution we are living in an ‘age of excarnation’, that is, an age in which the body is being removed from the human world. ‘No one can deny the extraordinary advantages of digital technology. The gains are too great to ignore out of some nostalgia for bygone times’, writes Kearney. But as he goes on to urge, we need ‘to remain sensitive to both cyber and carnal existence – to honour the vital human need for “double sensibility” : imagining and living in concert, touching and being touched in good measure.’ [1]

What might the art of painting have to tell us about the ramifications of this contemporary ‘excarnation’? As our lives become more and more pervasively computational and digital, recognizing the role of painting as a material and transformational medium is more important than ever.

On a basic level, the process of digital documentation entails the transfer of data from a source (a painting) to target medium (a digital image), a process that inevitably involves non-equivalence and incommensurability. But mediation between differences is especially problematic in relation to paintings that are non-representational and minimally composed, like Lee Ufan’s (or mine). A digital image of a work by a contemporary artist like David Hockney, for example, which is representational and has a visually complex composition, is far less deficient than a digital image of a typical painting by Lee Ufan, because in the case of the Hockney painting the transfer of data relatively accurately preserves the components of the representational image – a landscape setting with figures.

We are culturally conditioned, indeed, obliged, to accept digital images like these as credibly accurate reproductions of the paintings they document. The art market requires such proxies, but so too does our basic wish to access, understand, debate, share, and celebrate great art. Indeed, our society strives to make ever more accurate technologically produced copies using ever more sophisticated vision machines. But it is obvious that within normative utilitarian, educational, managerial, and mercantile contexts, the protocols of the documentation of painting are radically circumscribed.

We expect both an encounter with real paintings and with their digital documents to be meaningful. But it is obvious that the meanings derivable from real paintings are different in significant ways from those of the digital image of these paintings. Furthermore, the very evident deficit in relation to Lee’s painting exposes a more general inadequacy of photographic technology, which is designed to record only optical data and therefore misses very significant dimensions of an actual encounter with not just abstract paintings like Lee’s but paintings in general.

Let’s start with some basic empirical facts.

Holding up a digital reproduction of Lee Ufan’s painting next to the original will immediately demonstrate one obvious limitation of the former: the image is very small compared to the actual painting, which is 93cm tall by 73cm wide. This miniaturization means it is difficult or impossible to perceive the details of the real painting. If one is viewing the image on a computer, and the file is of sufficiently large dpi, one can zoom in on areas of the painting. If one continues to zoom in, or only have access to a smaller size image file, a pixelated image will be delivered. This immediately destroys the illusion that one has access to the visual properties of the original.

More fundamentally, one cannot get a sense of scale from a digital image. You can’t feel how the real painting relates to the human body. If the photograph was cropped to include wall and floor space and included a human presence, or the painting was documented in a time-based medium like video, this crucial sense of scale could to some extent be conveyed. But what it actually feels like to be there, moving around in front of the painting in real time and space, is obviously unavailable.

Mobile observations of the real painting by Lee will reveal that the support is quite deep – 4cm – which gives the work greater three-dimensionality than is common in relation to paintings - a tangible object-like presence. But this is inevitably lost in the immobile, flat, frontal, digital photograph. Again, a video will provide a greater sense of this quality, but unless it is interactive, provides a pre-determined sequence of movements. But even an interactive version depends on the vision provided by a lens attached to a machine not an eye embedded in a body.

You also won’t get much sense of the surface texture of Lee’s painting. He uses a relatively coarse grain linen canvas as his support, which is coated in several layers of gesso and oil paint. The small, solitary brush stroke that breaks the uniform off-white field of the painting, is quite thinly painted, and so in places the weave of the canvas beneath is visible. In a digital reproduction, in a book one sees the sheen of printer’s ink on paper, or on a computer screen, a glossy glass surface, while here, in this talk, a projected image using a powerful electric light beam.

Because of the vast improvements in digital photography over analogue in terms of colour matching, to a much greater extent than in earlier periods, we are likely to be lured into believing that we are actually perceiving the same colours as in the original painting. But a comparison between an image (still or moving) and the actual work by Lee will reveal that the former is not the same colours as the latter. This isn’t surprising. The pigment of Lee’s painting is suspended in oil and applied to linen with a brush, while the colour in a printed reproduction on paper is suspended in ink that has been mixed using the CMYK printing procedure. Viewing the image on a computer or monitor screen, meanwhile, involves perceiving colours generated by red-, green- and blue-coloured light. Each pixel of which the image is comprised contains three or four subpixels coated in phosphor, which are excited with UV light emitted by Xenon or Neon gas that turn to plasma state once an electric current is passed though. It is also important to note that we are seeing only an approximation to the colours recorded at a specific moment in time, in a specific light, by the photographer, whereas the colour of Lee Ufan’s painting changes in relation to the ambient light in which it is bathed, and also depending on the direction and proximity from which you look at it.

On reflection, we can all surely agree that on this basic phenomenological level we are experiencing a nugatory approximation to Lee Ufan’s original painting. We are only seeing what a single lens perpendicular to the painting attached to a machine controlled by a professional photographer who is focusing on a vertical surface, digital data that is subsequently manipulated on a computer by the photographer using software.

We can sum this all up by saying that while an encounter with the actual Lee Ufan is to a significant degree empirical - based on, concerned with, or verifiable by observation or experience – an encounter with its digital document will be nonempirical, abstract, or theoretical. By denuding a painting of its actual material properties and embeddedness in three-dimensional space, attention inevitably shifts to the non-sensory and mental. Because of the sensory deficits inherent in digital documentation, a viewer’s responses are inevitably biased towards intellectual consciousness. Attention is directed towards the kinds of mental processes that words can customarily encompass.

As a result, a digital photograph will inevitably fail to provide a resonant experience of the painting it documents. I use the term ‘resonance’ specifically, so as to refer to the recent sociological theory of Hartmut Rosa. Rosa asserts that ‘human beings are first and foremost not creatures capable of language, reason, or sensation, but creatures capable of resonance’.[2] Resonance is inherently anti-structural, and it is precisely because of this property that it is so highly valued. For what is at stake is the loosening of the rigid and alienating boundaries that usually ground the subject firmly in time and space. Resonance brings the experience of intimate connectedness to a world freed from the usual strong and deadening awareness of divisions and boundaries. As such, a resonant experience is inherently unpredictable, and it can be constituent of a situation or can be wholly absent, regardless of any active desire we might have to experience it. Furthermore, and importantly, in Rosa’s analysis, a resonant relationship to the world is inevitably only a brief and uncontrollable release from the pervasive state of alienation within which modern humanity exists.

The video ‘document’ in the exhibition Transfer is by the Belgian artist and Korean resident Rafaël featured ten Koreans standing in a row and responding to 4 questions about a digital photograph of the Lee Ufan painting, rather than the actual painting itself, which in the exhibition was hung a few meters away:

Rafaël. Lee Ufan, Dialogue (2014), oil on canvas. 2022. Colour, Stereo. 4 minutes

The questions appear on a blank screen, and then we see the camera trained on the 10 interviewees. We only see them responding to what they see, and their answers are heard simultaneously and therefore are mostly incomprehensible. The goal was to abandon the normative protocols of the digital document, to decisively upset the conventions.. The hope was that a less instrumental and more playful space might be opened up within which the relationship between the digital document and the painting that is the source can more fruitfully evolve.

If we want to ‘honour’ the ‘double sensibility’ of contemporary life to which Richard Kearney refers, we would surely do well to remind ourselves of the inadequacy of the paltry digital artefacts that masquerade as paintings. We need them, of course. They are indispensable documents. But we can also strive to maintain and encourage intimate acquaintances with works of art IRL. In real life.

NOTES

[1] Richard Kearney, Touch (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021), 132

[2] Hartmut. Rosa, Resonance. A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World. Translated by James C. Wagner (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 36

Lee Ufan image courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

You can see some of my paintings, for example, at: https://www.galleryjj.org/simon-morley.

Or, at my website: simonmorley.com.