‘North Korea: ‘a phenomenon of the very extreme and pathological right.’

The title of the post is a quotation from the British writer Christopher Hitchens, who wrote about the North Korean system in an article written in 2010. Hitchens began by recounting a visit to North Korea and how his minder had expressed racist views in such a way that it was obvious that such views were central to what, for him, was a quite normal and acceptable worldview. I think about how to understand this dreadful ideology within a wider context.

This photograph (not taken by me, although I’ve been there) shows North Korean border guards strutting their stuff just a few miles from where I’m writing this post, at Panmunjom, the only place where the DMZ narrows and the two Koreas meet. The title of today’s post is a quotation from the British writer Christopher Hitchens, who in 2010 wrote about the North Korean system in a much commented upon article. Hitchens began by recounting a visit to North Korea and how his minder had expressed racist views in such a way that it was obvious that these views were central to what for him was a quite normal and acceptable worldview. But his article was specifically motivated by reading the then recently published book by B. R. Myers entitled ‘The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters’. As Hitchens wrote, Myers described “the Kim Jong-il system as a phenomenon of the very extreme and pathological right. It is based on totalitarian ‘military first’ mobilization, is maintained by slave labour, and instills an ideology of the most unapologetic racism and xenophobia.“

Since then, under Kim Jong-Ill’s successor, his son Kim Jong Un, things have only gotten worse in the DPRK, and many analysts would agree with Myers’ general prognosis. For example, it seems obvious that to persist in describing the country as ‘communist’ is very misleading, not least because the DPRK itself doesn’t use the word anymore! Ideologically, it prefers to refers to ‘Juche’ thought, which is usually translated as ‘self-reliance’ and is intended to be a specifically North Korean ideology - the one Myers’ set about describing. But it is interesting to consider how the term ‘communist’ was initially adopted and then discarded in the DPRK.

The North Korean regime was put in place by the Soviet Union, whose forces occupied the northern part of the peninsula at the end of World War Two. The first of the Kim dynasty, the former guerrilla fighter in China Kim Il-sung, was installed by Stalin as a counterpoint to the American candidate in the south, Syngman Rhee. This is an archive photograph from 1946 of people in Pyongyang parading with portraits of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Kim Il Sung:

Subsequently, two rival Koreans came into being in 1948. In 1950, Stalin gave Kim the ‘green light’ to invade the Republic of Korea. By that time, China had also fallen to the Communists. After the failure of the invasion and the stalemate of the Korean War, the DPRK settled into being a client state of the Soviet Union (and to a lesser extent, China) until the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the abandonment of communism in Russia precipitated a humanitarian and ideological crisis in the DPRK. But by that time the country had already moved to established its own distinctly ‘Korean’ ideology of Juche. It is this ideology that Hitchens characterised as being on the far ‘right’ politically because its racist and xenophobic traits are not ones that could be associated with the far ‘’left’.

But to what extent is this ‘left’/’right’ polarity an accurate way of analyzing the reality of North Korea over the past thirty years?

*

Following the French Revolution in 1789, when members of the National Assembly divided into supporters of the old order sat to the president's right and those of the revolution to the left, it became customary in the West (and then internationally) to described politics in terms of ‘left’ and ‘right’. In the nineteenth century Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels described ‘communism’ ’as a radical politics of the ‘left’ that recognized the historical inevitability of class war within capitalist societies leading to a revolution after which all property would be publicly owned and each person’s labour paid for according to ability and needs. It was therefore specifically cast as the antithesis to the ‘right-wing’ ideologies of the industrailized capitalist societies in which property was privately owned and labour rewarded unevenly and in relation to entrenched inequalities rooted in class and race. ‘Communism’ thus became the portmanteau term of the twentieth century for ‘leftist’ radical politics directed towards revolution from below, which, after the Bolshevik revolution in Russia 1917, was monopolized by the Soviet Communist Party.

But for post-colonial Korea, ‘communism’ meant something very different. It involved adopting one of the only two route maps towards modernization provided by the globally dominant West. Under the guidance of the United States the Republic of Korea had chosen the capitalist map, while the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea chose the communist one. It should be noted that neither map included democracy in Korea at this initial stage.

In relation to the communist road map, it is important to consider that Korea was also very far from being an industrialized economy against which a Korean ‘proletariat’ (the actually almost non-existent factory workers) - could be seen to be struggling for freedom against their capitalist overlords. In other words, as also, indeed, in Russia in 1917 and China in 1949, the ‘communists’ ostensibly took power in countries that Marx and Engels would have considered economically and socially distant from the ripe and predestined moment of violent revolutionary transition. Nevertheless, the communist road map was the only one handed to the North Koreans by the Soviets. But soon enough, as in Russia and China, ‘communism’ had morphed into a Korean-style totalitarianism of the ‘left’, as opposed to the totalitarianism characteristic of the ‘right’, aka fascism. That, at least, was how the story was told.

We still basically see politics today in terms of the binary ‘left’ and ‘right’, which is why Hitchens could imagine only a choice between seeing North Korea as on the extreme political ‘left’ ‘(communism) or extreme political ‘right’ (fascism) As racism and xenophobia were part of the fascist package, they placed North Korea on the ‘right.’ But this shoehorning into familiar political polarities risks losing sight of significant specific characteristics - but also characteristics of importance more generally beyond North Korea. For it is increasingly obvious that these polarities inherited from the European nineteenth century, never did fit the Korean situation, but also no longer suffice to describe the current political situation more generally - in both the global north and south.

*

Back in the late 1940s some disenchanted former communists wrote a book entitled ‘The God That failed’, edited by the Englishman Richard Crossman (a former communist turned Labour Party Member of Parliament). Subtitled ‘A Confession’, it included the testimonies of, amongst others, the Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler, the French novelist André Gide, and the English poet and critic Stephen Spender. The book was a classic of the early Cold War. I remember that my father, a state school English teacher and life-long socialist and Labour Party voter, owned a copy of the English edition, and I read it as a teenager in the mid-1970s, and it probably helped me steer a moderate ideological course during the awful Thatcher years.

Koestler joined the Communist Party in late 1931 and left in early 1938, and became a very vocal critic. He begins his contribution by writing: “A faith is not acquired by reasoning…..From the psychologist’s point of view, there is little difference between a revolutionary and a traditionalist faith. All true faith is uncompromising, radical, purist”.

Koestler’s analyses still seems spot on, because what we are witnessing today is an overwhelming tendency to adopt a position based not on reason but on ‘faith’, a position that is reassuringly ‘uncompromising, radical, purist”. We can see this trait on both the ostensible ‘left’ and ‘right’, and it suggest another polarity which offers a more accurate diagnosis of our current situation. The characteristics described by Koestler encompasses both extremes within our current ideological situation – ‘Woke’ radical race theory and nationalist populism - putting them not at opposite ends of a political binary of ‘left’ and ‘right’ but rather together within a binary comprised of ‘faith’ rather than ‘reason’ based politics. In this context, it’s not so much a problem of what one believes but whether such belief is ‘faith’ based intransigence – rooted in the desire to hold to the belief uncompromisingly, and so to adopt the most radical and pure possibility - or rooted in a reality that is recognized as inevitably ambiguous and uncertain.

Another work that made an impression on me as a teenager in the late 1970s – courtesy of my History teacher, Mr. Reid – was philosopher Karl Popper’s ‘The Open Society and Its Enemies’. This two-volume study was written during Popper’s exile from the Nazis in New Zealand during the War and published in 1945. Popper’s discussion of the Western history of ‘closed’ societies from Plato to Hegel and Marx was way too sophisticated for my young mind, but his basic argument was one that I did understand, and also one that still seems to resonate. Popper wrote:

This book raises issues that might not be apparent from the table of contents. It sketches some of the difficulties faced by our civilization — a civilization which might be perhaps described as aiming at humanness and reasonableness, at equality and freedom; a civilization which is still in its infancy, as it were, and which continues to grow in spite of the fact that it has been so often betrayed by so many of the intellectual leaders of mankind. It attempts to show that this civilization has not yet fully recovered from the shock of its birth — the transition from the tribal or "enclosed society," with its submission to magical forces, to the 'open society' which sets free the critical powers of man. It attempts to show that the shock of this transition is one of the factors that have made possible the rise of those reactionary movements which have tried, and still try, to overthrow civilization and to return to tribalism.

I recently read a fine book by the author and historian of ideas Johan Norberg called ‘Open. the Story of Human Progress’, which was published in 2020. Norberg credits Popper with defining a central class of values which he wishes to promote as a model for society today. He writes:

Openness created the modern world and propels it forwards, because the more open we are to ideas and innovations from where we don’t expect them, the more progress we will make. the philosopher Karl Popper called it the ‘open society’. It is the society that is open-ended, because it is not a organism, within one unifying idea, collective plan or utopian goal. The government’s role in an open society is to protect the search for better ideas, and people’s freedom to live by their individual plans and pursue their own goals, through a system of rules applied equally to all citizens. It is the government that abstains from ‘picking winners’ in culture, intellectual life, civil society and family life, as well as in business and technology. Instead, it gives everybody the right to experiment with new ideas and methods, and allows them to win if they fill a need, even if it threatens the incumbents. Therefore, the open society can never be finished. It is always a work in progress.

When read in the light of the regime now oppressing North Korea, what Popper and Norberg write provide useful insights. The regime is almost a caricature of the ‘closed’ society. But more broadly, they suggest that we should move on from the binary ‘left’ and ‘right’ and instead see the situation in terms of those who practice politics on the basis of ‘faith’ compared those doing it on the basis of ‘reason.’ Unfortunately, all too often a position based on dogmatic ‘faith’ is the more appealing option, as it means one doesn’t have to qualify one’s beliefs by taking into consideration conflicting attitudes, positions or information. In short, one can dispense with doubt. As Sam Harris puts it, ‘faith’ in this sense means ‘what credulity becomes when it finally achieves escape velocity from the constraints of terrestrial discourse - constraints like reasonableness, internal coherence, civility, and candor.’ Harris was aiming to expose religious faith, but what he says could equally apply to extreme secular ideological faiths, too. Isn’t North Korea a system that has definitely achieved ‘escape velocity from the constraints of terrestrial discourse’?

Ultimately, what we should be striving for is a way of thinking about society that incorporates doubt and that turns away from the temptations offered by any models - religious or secular - that try to banish doubt and install certainty. The terms ‘open’ and ‘closed’ seem to me to be useful titles of more realistic road maps than ‘left’ and ‘right.’

*

Norberg is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, DC, an organization that is often described as a hotbed of neoliberalism, and you can see how Norbert’s paean to ‘openness’ (like Popper’s) could easily be construed as providing a green light for capitalist free trade globalist maximalism. For Norberg’s optimistic version of the ‘open’ society seems wedded to an ideal of progress coupled to western style capitalism-driven globalization at a time when we recognize that it is precisely this ambition that has precipitated the dire global ecological crisis.

What would an ‘open’ society be like that isn’t founded on capitalist globalization and an obsession with progress in material terms, and instead was based on responding to what the philosopher Bruno Latour calls the ‘Terrestrial’, that is, on a kind of ‘openness’ to the planet as a whole, rather than just on narrow human needs and aspirations.

In 2018 the DPRK emitted 44.6 million tonnes of greenhouse gas, while the ROK emitted 758.1 million tonnes! So this particular ‘closed’ society is a far less brutal ecological force than the ostensibly ‘open’ one with which it shares the peninsula. But obviously, such a small carbon footprint has not been achieved by benign design, rather it came about by complete chance, and as a beneficial side-effect of being an unapologetically racist and xenophobic society. Ironic, isn’t it?

NOTES

The photo at the beginning of the post is a screen grab from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/north-korean-soldier-makes-midnight-dash-to-freedom-across-dmz/2019/08/01/69da5244-b412-11e9-acc8-1d847bacca73_story.html

The archive photograph: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1946-05-01_평양의_5.1절_기념_행사%282%29.jpg

Christopher Hitchens’ article:: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2010/02/kim-jong-il-s-regime-is-even-weirder-and-more-despicable-than-you-thought.html

B. R. Myers book: https://www.amazon.com/Cleanest-Race-Koreans-Themselves-Matters-ebook/dp/B004EWETZW

Johan Noberg’s book: https://www.amazon.com/Open-Story-Progress-Johan-Norberg/dp/1786497182

Sam Harris’ book ‘The End of Faith’: https://www.amazon.com/End-Faith-Religion-Terror-Future/dp/0393327655

The carbon footprint statistics are from: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/climate-action/what-we-do/climate-action-note/state-of-climate.html?gclid=EAIaIQobChMInsbXo4ng_wIVU4nCCh2UwgDbEAAYASAAEgKAQPD_BwE

Police State?

While I was in London I visited Tate Britain and saw an exhibition of recent fresco paintings by Rose Hastings and Hannah Quinlan. The works were pretty good, but were justified by the duo of artists as about living in Britain’s ‘police state’. Really?

A fresco painting from Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan’s exhibition, ‘Tulips’, Art Now, Tate Britain.

While I was in London I visited Tate Britain and saw an exhibition of recent fresco paintings by Rose Hastings and Hannah Quinlan. The works were pretty good, but I was put off when I read on a wall label that they were justified by the duo of artists as a reaction to living in Britain’s ‘police state’.

Really? Britain is most certainly very far from paradise, but it is absurd to describe it as a ‘police state’. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, whose hazy mountains I glimpse in the distance as I walk my dog in the morning, is a ‘police state’. Do these feted British artists think the masters of a real ‘police state’ would permit them to show their work in a public institution and have it discussed in the media? Of course not. Britain is a ‘police state’ only for those who has a very melodramatic sense of the dysfunctional nature of their local social reality. Britain is a fuck-up in many ways – not least because of Brexit and increased policing powers - but it’s also an extraordinary place in which people have a degree of freedom that is the envy of millions in less fortunate nations.

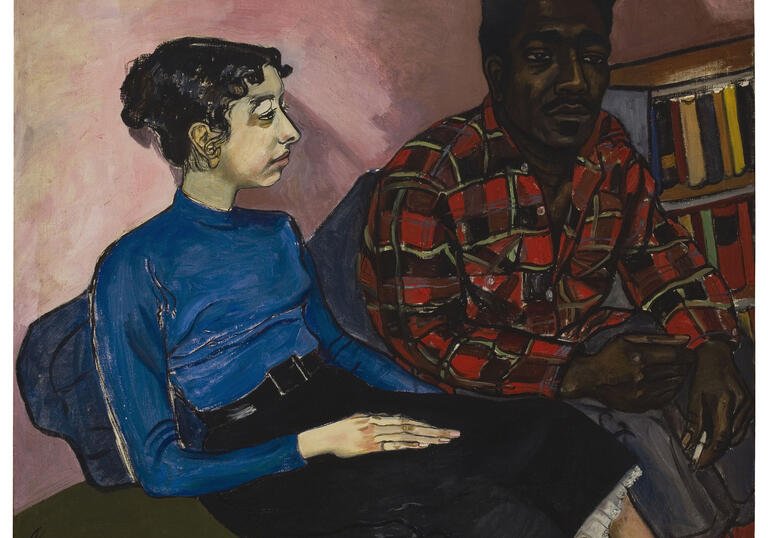

I also saw the wonderful Alice Neel exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery. Here is one of her works:

Alice Neel, ‘Rita and Herbert’ (1954).

I didn’t know much about Neel beforehand, and was surprised to discover that she was a paid up member of the American Communist Party. In 1981 she was the first living artist to have a retrospective in the Soviet Union, and in an interview in 1983 said, ‘the whole 20th century has been a struggle between communism and capitalism’. Neel was a fantastically penetrating and empathetic portraitist but was clearly ideologically myopic. In this, of course, she was very far from alone amongst artists and writers.

This is what Picasso wrote in 1944, after having recently joined the French Communist Party:

I would have liked better to have replied to you by means of a picture’, he told us; ‘I am not a writer, but since it is not very easy to send my colours by cable, I am going to try to tell you.’ ‘My membership of the Communist Party is the logical consequence of my whole life, of my whole work. For, I am proud to say, I have never considered painting as an art of simple amusement, of recreation; I have wished, by drawing and by colour, since those are my weapons, to reach ever further into an understanding of the world and of men, in order that this understanding might bring us each day an increase in liberation; I have tried to say, in my own way, that which I considered to be truest, most accurate, best, and this was naturally always the most beautiful, as the greatest artists know well. Yes, I am aware of having always struggled by means of my painting, like a genuine revolutionary. But I have come to understand, now, that that alone is not enough; these years of terrible oppression have shown me that I must fight not only through my art, but with all of myself. And so, I have come to the Communist Party without the least hesitation, since in reality I was with it all along. Aragon, Eluard, Cassou, Fougeron, all my friends know well; if I have not joined officially before now, it has been through ‘innocence’ of a sort, because I believed that my work and my membership at heart were sufficient; but it was already my Party. Is it not the Communist Party which works the hardest to know and to construct the world, to render the men of today and tomorrow clearer-headed, freer, happier? Is it not the Communists who have been the most courageous in France as in the USSR or in my own Spain? How could I have hesitated? For fear of committing myself? But on the contrary I have never felt freer, more complete! And then I was in such a hurry to rediscover a home country: I have always been an exile, now I am one no longer; until the time when Spain may finally receive me, the French Communist Party has opened its arms to me; there I have found all that which I most value: the greatest scholars, the greatest poets, and all those beautiful faces of Parisian insurgents. (1)

Wow! Poor old Picasso. ‘Is it not the Communist Party which works the hardest to know and to construct the world, to render the men of today and tomorrow clearer-headed, freer, happier?’ What a dupe! We should probably re-write this as: ‘Is it not the Communist Party which works the hardest to know and to construct the world, to render the men of today and tomorrow less clearer-headed, less free, despairing?’ But Picasso was very far from alone in his delusion, as he himself noted.

I’m sure this essentially emotional response to injustice and the belief that the most powerful force struggling against this injustice was communism was also what lay behind Alice Neel’s commitment, which went back to the 1930s. It certainly wasn’t obvious in 1944, and still wasn’t in 1983, prior to the end of the Cold War, that the struggle that Picasso saw as between revolution and reaction, and Neel as between communism and capitalism was actually between the utopians who wanted change now, and the pragmatic social reformers who saw change as occurring one small step at a time. Of course, the former types seem much more glamorous and dynamic. Slow social reform is so very dull. So very bourgeois.

If you reflect on the history of modern art, you soon get the impression that the artists we nominate as the progressive voices of our times are mostly in the revolutionary ‘change now’ camp. They wanted things to get better immediately. This isn’t surprising, as there’s so much wrong in past and present society that the visceral response of any sensitive soul is bound to be one of deep disgust and the desire to right wrongs without delay. But the sad fact is that history shows that revolutionary radicalism never works in practice. In fact, it tends to make things worse not better, because it alienates so many people – for instance, all those justifiably anxious about the new, the unknown, the untested.

As time went by, being a communist required more and more self-deception. Maybe being a communist before the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact of 1939 was possible on the basis of a sound appraisal of available evidence. Maybe in 1944 it was possible because of the central role played by European communist parties in the struggle against Nazism. But after the Korean War of 1950 -53, the Hungarian Uprising of 1956, the Prague Spring of 1968? To still be a communist in the 1980s required a very high level of dissemblance, of ignoring many awkward facts. But where faith is concerned, facts are of small importance.

NOTES

(1) Published in L’Humanité, 29-30 October 1944. https://theoria.art-zoo.com/why-i-joined-the-communist-party-pablo-picasso/

Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan, ‘Tulips’ is at Art Now, Tate Britain, 24 Sep 2022-7 May 2023. Image courtesy of Tate. https://www.newexhibitions.com/e/60066

Alice Neel: Hot Off The Griddle is at Barbican Art Gallery, 16 February - 21 May 2023. Alice Neel image courtesy of The The Estate of Alice Neel.