MBTI, Five Elements, Ketsueki-gata, and Urbanization in South Korea

I consider the possibility that the basic transformation in the physical environment caused by rapid modernizing development goes a long way to explaining Korean people’s shift from an essentially agricultural and process-oriented model of human personality to a mechanistic, abstract, and ‘managerial’ one typified by MBTI.

The Chinese Five Element Model.

In a couple of previous blog posts I mentioned the way in which the personality profiling typology MBTI is big in South Korea, and how it reflects a specific techno-managerial mindset that has been adopted as part of the Westernizing-modernizing ‘package’. What is also interesting about Korean people’s use of MBTI is how it fundamentally differs from the previous models through which they have sought to stabilize and order personality identification. This difference reflects basic changes in the human geography of the country, most especially, the urbanization of society.

In pre-modern Korea a dominant model called ohaeng (오행), which derived from Chinese Taoism and Confucianism,, dominated. Here, there are said to be 5 personality types based on the five element cycle - Wood, Fire, Metal, Water, Earth. These in turn relate to the cyclical changing of the seasons each year. The Five Element Theory is also the basis for the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac. It was said that people can be classified according to the five elements. Their body structure, tendencies, temperaments, emotions, positive and negative behaviour, moods and illnesses can all be considered in relation to them because the seasons correlate with human taste, emotion, internal organs, and parts of the body. Therefore, the Five Element theory is the basis for ‘Oriental’ or ‘Chinese’ medicine. The general goal was to devise a system that reflected the relationship and interdependence of everything, and it considered that human well-being fundamentally depended on finding a balance within the dynamic on-going and unfolding process of existence.

Apparently, I am classed as ‘Earth’. Here is what the International College of Oriental Medicine website says about me:

Earth type people have a yellowish complexion, round faces and big heads, big abdomens, small hands and feet and plenty of muscles. They have a sing-song voice. They are calm in temperament, fond of helping people and like to be involved and needed.

They love to associate with other people, seek harmony and togetherness and insist upon loyalty, security and predictability. They have a dislike of power. The emotion associated with the Earth element is Rumination. When a person is overly pensive and contemplative, he/she can easily become fixated on worrisome thoughts and ideas.

Earth type people can therefore often be tormented by their over-concern for details and can become caught up in circular thinking from which there is no escape. Other people can depend on this type of person because they are reliable, sympathetic, and good caretakers.

Without the demands of work or responsibility to others, they can become inert, dropping back into the well-worn trails of their own mind. In this state, their energy becomes stagnant and leads to poor digestion, heaviness and flabbiness. They need to balance their devotion to relationships with solitude and self-expression, developing self-reliance as well as building community.

They have a tendency for excess eating and good living that leads to obesity, stomach ulcers and diabetes. They may suffer from disorders of the joints, particularly arthritis, and especially involving the wrists and ankles. Woman often have irregular menstruation with weight gain from cycle to cycle and men are prone to early prostatitis.

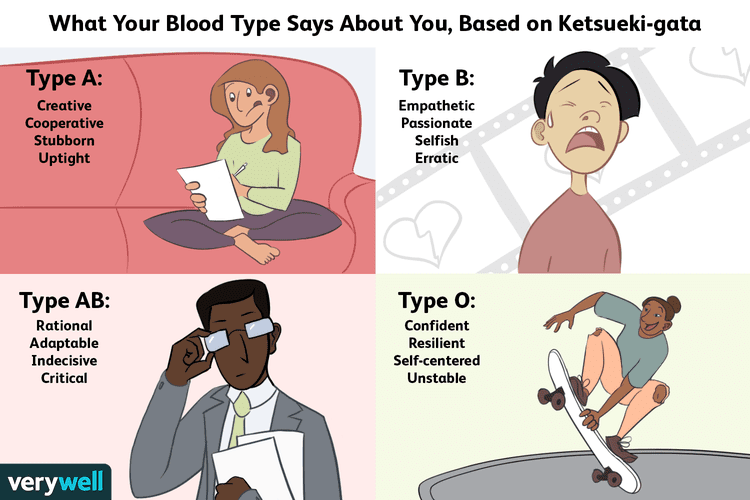

I don’t recall any Korean talking to me about ohaeng as a way of discerning my personality type, but I do remember being asked by several Koreans when I first met them for my blood group, something I didn’t actually recall - a fact that dumbfounded them. This is because they believe you can classify personality types according to blood type, like this:

This personality typology derived from Japan, where it is called Ketsueki-gata. But its looks like the Blood Type model has now been superseded by MBTI, especially amongst young South Koreans.

What is especially striking about the evolution of personality typologies over the past one hundred years in Korea is that is reflects the systematic removal of notions of human identity from being embedded in nature. Whereas the traditional Chinese derived typology linked humanity to the four seasons and the idea of existence as process, and the Japanese Blood Type model linked it to the body, what HBTI effectively does is sever any such conception of personality from the natural world, rendering human personality abstract and autonomous.

In other words, South Koreans are following the West in assuming there is a fundamental division between the human and the non-human worlds – between ‘culture’ and ‘nature.’ The benefit of such dualism lie in the capacity it nurtures for a dominating and exploitative relationship to the non-human, a relationship in which humanity comes to see itself as standing apart from the rest of the world. This dualistic stance is fundamental to the techno-scientific mindset of modernization. As the philosopher and ecofeminist Val Plumwood noted of the rationalistic spirit that dominates Western culture: “Its ‘success-making’ characteristics, including its ruthlessness in dealing with the sphere it counts as ‘nature’, have allowed it to dominate both non-human nature and other peoples and cultures.”

In practical terms, this shift in the conception of human personality reflects the wholesale migration of people from the land and dependence on agriculture to the city and factory and office employment. One of the most striking features of contemporary South Korea is its relentless urbanization: 20 percent of the population lives in Seoul. Greater Seoul encompassed more than 50 percent of the total population. Over the past fifty years South Korea’s urbanization rate has exceeded 90 percent. This is what the National Atlas of Korea, published online by the Seoul Institute, says:

The government’s master plan for land development was put into action in the early 1960s. At that time, the government based its plan on the growth pole theory in order to maximize the development effect in as short a period of time as possible. Though wellintentioned, the growth pole approach only allowed for investment in the few central development areas that were most likely to succeed before development could be considered in other areas. This approach had the unfortunate result of causing both people and capital to flow to those few development centers. The resulting imbalance between those centers and all other areas in the country was later corrected with the implementation of a more balanced set of development policies.

…….

Urbanization has had major impacts on the country's demographics, its physical landscape, its socialbehavioral institutions, as well as the economy. Symbols that represented cities on the national map kept increasing, and as the number of cities increased, the population of rural areas declined, which also led to a decrease in the percentage of the population that was engaged in agriculture and fishery activities. New cities kept appearing on the national map as larger metropolitan areas continued to expand into rural land surrounding them. The emergence of metropolitan centers is a major feature of development in Korea and resulted primarily from the rural-to-urban migrations, especially in the capital area. After the 1960s, rapid urbanization and industrialization attracted secondary and tertiary industries to cities as well. More jobs were created prompting further mass migrations from rural to urban areas. The urbanization rate, which indicates the ratio of urban population as a percentage of the total population, increased rapidly in Korea until the 1980s, but the pace has slowed since then. Between the 1970s and 1980s urbanization occurred at a much faster rate than in many other countries. As a result, rural areas suffered from the lack of a labor force, a decrease in the coefficient of land utilization, and the rapid aging of its population; these factors ultimately contributed to the failure to meet the minimum requirements for sustaining a rural community in many instances. And at the same time urban areas were confronted with the need to mitigate the challenges of overcrowding. Additionally, the heavy concentration of industrial activity within the metropolitan areas resulted serious social and environmental issues such as housing shortages, traffic congestion, poor air quality, and overall environmental degradation.

It seems to me that this basic transformation in the physical environment caused by rapid modernizing development, in addition to the concomitant transformation in mindset entailed in adopting the Western model of a culture/nature dualism, goes a long way to explaining Korean people’s shift from what is an essentially agricultural and process-oriented model of human personality to a mechanistic, abstract, and ‘managerial’ one. In this context, Ketseuki-gata seems like a transitional typology in which the seemingly Western ‘scientific’ criteria of blood types, with its underlying assumption of fixed and mechanistic principles, were melded with residual principles from the Chinese Five Elements model based on the alternative process-based vision that pervaded East Asia.

Ironically, Western thinkers are now shifting their mindset to embrace just such a process-based vision so as to better confront climate change…..More on this in a future post.

Sources:

The Five Element diagram is from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wuxing_%28Chinese_philosophy%29

The International College of Oriental Medicine quote is from: https://orientalmed.ac.uk/the-five-personality-types-by-galit-hughes/

The Ketsueki-gata illustration is from: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-blood-type-personality-5191276

The Val Plumwood quote is from: Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason, (Routledge, 2002), page 5

The quote from the National Atlas of Korea is from: http://nationalatlas.ngii.go.kr/pages/page_592.php

MBTI. Some more thoughts

Some more thoughts on the MBTI craze in Korea, and its relationship to modernization in general.

A screen-grab from the website ‘16Personalities’ - one of the most popular in South Korea for learning about MBTI.

In the previous post I discussed young Korean people’s enthusiasm for MBTI personality profiling and argued that one of the reasons why MBTI has become so popular here is that it provides the possibility of organizing the messy reality of human identity in an efficient manner that draws attention only to positive character traits.

In this post I want to dwell on the word ‘efficiency’ and its role in Korean society. I think there’s no doubt that visitors to the Republic of Korea are likely to be struck by the feeling that this country is highly efficient. I don’t think I’ve ever waited for a subway or mainline train because it’s late. The country has the fastest broadband internet connection. When Koreans decide to emulate something foreign they always seem to do it with greater efficiency.

The contrast between the contemporary inefficiency of Western European societies (the ‘Wild West’, as I like to call it nowadays) and the ROK’s obvious efficiency was especially striking during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the recognition has stayed with me even after things are moving back to some kind of ‘normal’.

This ‘efficiency’ is all the more striking because in the early days of contact with the West and the initiation of modernization first under the Japanese, and then under the watchful eyes of the military government between the 1960s and 1980s, it was precisely the nation’s inefficiency that was criticized – both by foreigners and by Korean modernizers. Ahn Sang-ho (1878 – 1938), a prominent politician and independence activist under Japanese colonial rule, one of the first Koreans to emigrate to the United States who then in 1926 returned to Korea and engaged in anti-Japanese activism for which he was imprisoned - an experience that led to the ill health that caused his death - deplored Koreans’ parochialism, depravity, laziness, and dependence.

Ahn called for a radical reform of social behaviour through education and self-cultivation, but the spirit of modernization he admired in the West, which had led to the exponential expansion of the West’s wealth, power and influence, and the establishment of a democratic political system, was also fundamentally driven by what the German sociologist Max Weber (1864 – 1920) termed ‘bureaucratization’. This involved the organization of Western society around functional, formal, rational systems with well-defined rules and procedures. It required hierarchy, specialization, training, impartiality and managerial loyalty. A society moved through rationalization towards greater efficiency and effectiveness, and this in its turn meant that the citizens would reap the benefits in terms of greater security and wealth. But Weber warned that excessive reliance on and adherence to rules and regulations also inhibited initiative and growth. The tendency is for a managerial-bureaucratic society to treat people as machines rather than individuals. In other words, the system is de-humanizing. There is the danger that emotions and feelings are not incorporated into the way a bureaucratic society is run. The impersonal approach to the organization of a society shunts these dimensions of human existence to the margins, dismissing them as obstacles to social efficiency. For Weber, the systematic ‘dis-enchantment’ of the world was the price of rationalization. Technological expertise replaced priestly vision, and rationality and efficiency replaced mystery and magic.

Is it too much to say that in its avid desire to join the ranks of modernized nations, the ROK adopted a version of the Western bureaucratic model, one that from the 1970s onwards proved to meld very effectively with elements of pre-modern Confucianism, such as social hierarchy and the sense of the community as a collective rather than made up of individuals? Is it too much to suggest that young Korean’s weakness for MBTI today is a side-effect of the excessively bureaucratic version of capitalist modernization adopted by the ROK, manifested on the level of questions pertaining to personal identity?

Another screen-grab from 16Personalities.

*

In the previous post I mentioned the cultural theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, members of the so-called Frankfurt School and exponents of ‘critical theory’ – critical’ being the key word. For these left-leaning German Jews, writing in the wake of Hitler’s rise in Germany and Stalinism in the Soviet Union, its seemed that modernization in general was fundamentally unhinged. They believed the seemingly ‘open’ and democratic United States was simply more insidiously ‘fascistic’ than the obvious culprits. Capitalist modernity was synonymous with the degradation of human life to a level where the experience of alienation from the world and from each other was pervasive. Building on the social theory of Weber and others, they diagnosed modern society as having shrugged off one metaphysical system for another – religion for rationality.

In the more recent writings of the Frankfurt School sociologist Hartmut Rosa, which I have also mentioned in an earlier post, the uncompromisingly bleak prognosis of Adorno and Horkheimer cedes to a more nuanced perspective on the price of modernization. Alienation is still the norm, but Rosa stresses that modernization is also unique in seeking multiple remedies for alienation. One such remedy is art. Others include pop music and getting drunk or high - anything that can perhaps deliver the antithesis of alienation, which Rosa calls the experience of ‘resonance’. This benign world-relating to which Rosa refers is fugitive, structureless, and inherently invisible. “[R]esonance is not an echo, but a responsive relationship, requiring that both sides speak with their own voice”, Rosa writes in Resonance. A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World (2019). It is precisely because of the anti-structural properties of resonance that it is so highly valued and desired, because ultimately what is at stake is our profound yearning for a relationship to the world that is without hierarchy, divisions, and boundaries, in which we feel a deep sense of sharing, intimacy and harmony, and where all people and things are equal. Rosa’s choice of the term ‘resonance’ is largely determined by its anti-structural nature, and indicates that benign relationships with the world involve responsiveness on both sides – of the subject and the world. For Rosa argues that “resonance appears not as something that first develops between a self-conscious subject and a ‘premade’ world, but as the event through which both commence”. The experience of resonance can therefore only potentially occur when there is “a relation between two bodies that are at once open enough for a relationship while at the same time remaining sufficiently stable and closed so as to ‘sound’ at their own frequency or ‘speak with their own voice’.”

Rosa sees all people in developed countries as living lives mainly of alienation, and considers this to be primarily because modernity is inherently about aggressive control. As Rosa puts it in his most recent work to be translated into English, The Uncontrollability of the World (2020): “Modernity has lost its ability to be called, to be reached” becausewithin in it “[w]e are structurally compelled (from without) and culturally driven (from within) to turn the world into a point of aggression. It appears to us as something to be known, exploited, attained, appropriated, mastered, and controlled. And often this is not just about bringing things – segments of world – within reach, but about making them faster, easier, cheaper, more efficient, less resistant, more reliably controlled.” Rosa sees four dimensions to modernity’s obsession with guaranteeing maximum control which thwart the possibility of achieving resonance: the world is made visible and therefore knowable by “expanding our knowledge of what is there”, the world is made physically reachable or accessible, manageable, and the world is made useful. As a result, the price of achieving a historically unprecedented degree of control is that the modern subject exists mostly in a condition of profound alienation, inwardly disconnected from other people and from the world.

It seems to me that the contemporary Republic of Korea is especially prone to this rage for control, and that the craze for MBTI is one manifestation of this overwhelming tendency which is an intrinsic part of the modernization process through which the ROK has gone at breakneck speed. As Rosa writes: “Modernity stands at risk of no longer hearing the world and, for this very reason, losing its sense of itself.”

In a future post I will consider how MBTI can also be understood within a broader Korean historical and cultural context that predates Westernization. I will also explore how in the West the alientation of which Rosa writes plays out in terms of a lack of the very secure identity sign-posts that MBTI provides Koreans, and is causing so much trouble. Perhaps the South Koreans may be recognizing something important we in the West are not…...

References

The image at the beginning of today’s blog is from: https://www.16personalities.com/country-profiles/republic-of-korea

Max Weber’s ideal type of bureaucracy was described in Economy and Society, published in 1921.

Hartmut Rosa’s books are Resonance. A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, translated by James C. Wagner, and published by Polity Press in 2019, and The Uncontrollability of the World, also translated by James C. Wagner, and published by Polity Press in 2020..

Korea goes crazy for MBTI

Last week in class, one of my students mentioned how Koreans her age (the so-called MZ Generation) are seriously into MBTI – the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator personality assessment test. As I soon discovered on trawling the Internet, MBTI is practically an obsession amongst the young here in Korea. Why?

Last week in class, one of my students mentioned how Koreans her age (the so-called MZ Generation) are seriously into MBTI – the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator personality assessment test. As I soon discovered on trawling the Internet, MBTI is practically an obsession amongst the young here in Korea.

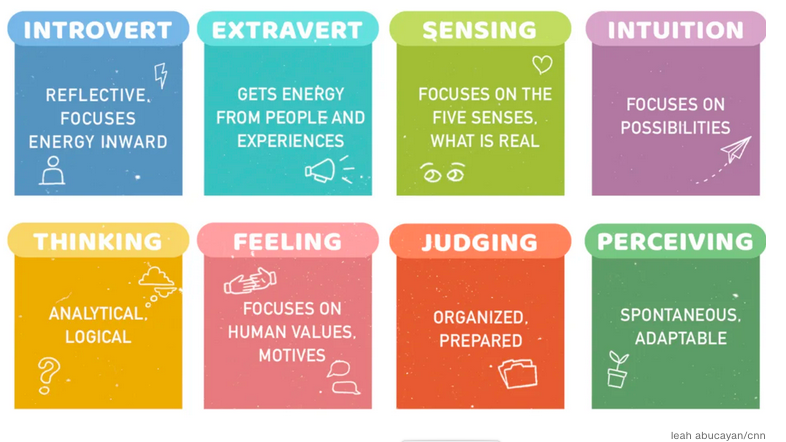

So, what is MBTI? It was devised in 1943 in the United States by a mother-daugher team, Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs-Myers. They were inspired by Carl Jung’s analytic psychology, but neither had professional training in psychology. This didn’t stop their personality assessment questionnaire taking off. It appealed to anyone who wanted simple answers to very complex questions, a clear map to the wilderness of the human mind. MBTI was therefore appealing to huge corporations and confused teenagers.

These are the basics personalities you can choose from:

The eight basic types combine to produce 16 composites, ranging from ISFP (Introvert-Sensing-Feeling-Perceiving) which make you kind, spontaneous, and accommodating, to ENTJ (Extravert-INtuitive-Thinking-Judging), which means you are confident, innovative, and logical. Of the latter, the website Truity, which has the by-line ‘Understand who you truly are’, says that it ‘indicates a person who is energized by time spent with others (Extraverted), who focuses on ideas and concepts rather than facts and details (iNtuitive), who makes decisions based on logic and reason (Thinking) and who prefers to be planned and organized rather than spontaneous and flexible (Judging). ENTJs are sometimes referred to as Commander personalities because of their innate drive to lead others.’

Here is the full menu:

If only it was so damn simple! Jung must be turning in his grave. He is on record as saying that MBTI profoundly misunderstood his analysis of personality. First of all, the assumption of MBTI is that you have a stable, fixed personality that is fully accessible to conscious self-reflection, that we are objective in our appraisal of our own personality traits. Secondly, you will note that according to Myers-Briggs, everyone’s personality is basically comprised of positive traits. This is very far from the thinking of the man who urged us to descend deep into the murky darkness of our consciousness, where we must face our ‘shadow’. As Jung wrote: ‘Unfortunately, there can be no doubt that man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself to wants to be.’ It is also obviously very different from the prognosis of Jung’s mentor and then rival, Sigmund Freud, concerning human nature (think, Oedipus Complex, the ID, and the Death Instinct).

MBTI is a sanitized, feel-good bowdlerization of very complex modern, but now dated, insights into the human psyche. In fact, if it wasn’t such an influential test, one might dismiss it as innocent fun, like astrology. And now, eighty years after it was first devised, and on the other side of the world, MBTI has been especially adopted by South Koreans. They are far and away the most avid adopters of the test, and the MBTI categories are routinely used in formal and informal social situations, and as a dating tool. Why?

There are several obvious reasons. Above all, perhaps, there is the influence of Korea’s collectivist social structure. This inclines individuals to seek to identify themselves not as independent, unique, selves but as members of clearly defined groups. In other words, as I noted in a previous post, when considering their identity, Koreans tend to struggle to associate their private self with a publicly recognizable self. But MBTI facilitates this by providing sixteen clear personality types. As Sarah Chea writes in the Korea JoongAng Daily: ‘Koreans tend to easily feel anxious when they think they don’t belong to any groups, so they push themselves to be involved so they can belong somewhere. They like to feel the sense of community from being with others in the same group, and feel relief when they feel they are not alone.’

Then there is the fact that Covid-19 pandemic accentuated people’s sense of isolation, making young Koreans even more desirous of connecting with others through explicit shared criteria concerning identity. Social media made this possible, but also required radical simplification. It’s much, much easier to say ‘I’m ESFJ’ than to struggle with the vague and shifting reality of one’s personality. But only, of course, if one is confident whoever is reading knows what you mean. MBTI therefore also serves to establish clear in-group/out-group boundaries not just within the 16 different personality types but in relation to assessing people in terms of those who have adopted the MBTI vision as a whole and those who have not.

This desire to share one’s personality with others is surely motivated by the need to feel less alone, but also by the fact that we now live in a culture in which self-realization is highly valued. The era we are now living through has radically altered how we think about ourselves, making the private self a ‘bankable’ commodity. But as the philosopher Han Byung-Chul notes, the deepest problem for people in the developed world is excessively positive attitudes which lead to a pervasive failure to manage negative experiences. This is surely another reason why MBTI is appealing. It allows us to gesture towards the interiority required of the fully contemporary identity while seeing ourselves only in relation to positive personality traits.

If we look at MBTI historically, we can recognize that it was born during a period in the United States when there was a drive towards the instrumentalization and rationalization of society in the service of the bureaucratic thinking central to a managerial capitalism, and tied to the immediate need to optimize efficiency for the war effort. As noted by the Frankfurt School thinkers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer – who when Myers and Briggs-Myers devised MBTI were living in the United States in exile from Nazi Germany – instrumental reason privileges the objective at the expense of the subjective, and obscures the fact that so-called ‘reason’ is always a mix of the rational and the irrational, the subjective and the objective. As a result, the objective is viewed as unchanging, eternal, and universal.

This is precisely what MBTI does in relation to personality and identity. Which means Koreans are placing the need for ‘efficiency ‘ in relation to achieving their ends above all other possible motives and desires. They are coping with the hyper-novelty, stresses and strains of accelerated modernization and westernization in their country by resorting to a blatant example of objective, instrumental reason, deployed in relation to the intimate and vulnerable region of their inner experiences - their personalities where, in reality, subjective experience reigns. This will surely inhibit any genuine exploration of identity. As Jung wrote: ‘The darkness which clings to every personality is the door into the unconscious and the gateway of dreams.’

By channeling the desire to present one’s private self in public without risk, through sanitized publicly accessible categories, MBTI is certainly a useful tool of social conformity. It is a million miles away from the profound crisis of identity evident in the West’s preoccupation with gender dysphoria. So, perhaps I am being too negative. In this cultural light, perhaps MBTI is a valid means of ensuring social stability.

Or perhaps most young Koreans think of MBTI as just a fun way of referring to each other, a game, and take it all with a big pinch of salt.

SOURCES:

The MBTI tables are from: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/22/asia/south-korea-mbti-personality-test-dating-briggs-myers-intl-hnk-dst/index.html

Truity quote: https://www.truity.com/personality-type/ENTJ

Korea JoongAng Daily quote: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2022/04/16/why/korea-mbti-blood-types/20220416070206510.html

Han Byung-Chul’s views can be found, for example, in The Burnout Society (Stanford University Press, 2013)

Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s ideas concerning ‘instrumental reason’ can be found in Critique of Instrumental Reason (Verso, 2013)

Carl Jung’s writings are voluminous. A good place to start is Modern Man in Search of A Soul (1936) which is available in a new edition from Routledge. The Amazon blurb is telling: ‘One of his most famous books, it perfectly captures the feelings of confusion that many sense today. Generation X might be a recent concept, but Jung spotted its forerunner over half a century ago. For anyone seeking meaning in today's world, Modern Man in Search of a Soul is a must.’