‘Flood the Zone with Shit and Howling’. Lessons from North Korea

Sometimes, I’m grateful to North Korea for helping me to see more clearly what’s happening in the world more generally. In this case, their ‘noise-bombing’ and balloon sending has helped me understand President Trump.

A balloon from North Korea carrying garbage and excrement lying in a South Korean rice field in the Spring of 2024.

These days, a deliberately unsettling medley of sounds are being blasted across the DMZ by North Korea. It’s what’s known as ‘noise bombing’, a nasty aural dimension of psychological warfare. The sounds mostly consist of deep apocalyptic droning, wailing sirens, and on occasion, screaming women and howling wolves. We can sometimes hear some of the sounds in our village - it depends how strong the wind is blowing from the north - but so far, I’ve only been able to detect the droning and sirens. South Korea sends its own ‘noise bombs’ towards the North - K-Pop music and other good news about living in a free country. Before, when the North noise-bombed the South they also used patriotic music and loud-speaker announcements about how their country is a workers’ paradise.

This new unsettling development signals a change in strategy in which the North no longer uses ‘noise-bombing’ as propaganda in the obvious sense. The change parallels another new strategy: sending helium balloons across the border which now are not filled with DPRK propaganda, as before, but with garbage and human and animal excrement. So far, none have come down near our village, so I have only seen them in the news media. This is ostensibly a response to actions originating in the South - balloons sent by North Korean defector groups and Christian organizations which contain propaganda. In fact, it’s an illegal activity in the South, but nevertheless continues to be a regular occurrence..

Both the howling and the shit are a reflection of Kim Jong-un’s declaration that North Korea’s goal is no longer a re-united Korea, and that the South is now an implacable enemy to be ultimately destroyed. This has, of course, been the truth since the Korean War, but until last year the North persisted in maintaining the fiction of reunification as an inclusive aspect of their much bigger fiction – that of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as a whole. This fiction included the assumption that the people in the Republic of Korea were oppressed and just waiting to be liberated by the North. Now the North has re-written or erased part of the official narrative, evidently because it no longer serves any practical purpose, and can be discarded without threatening the status quo in the North. as I noted in my previous post, there are obvious reasons for the change in relationship. Almost no one in the North is old enough to remember when there was just one Korea, and who perhaps have relatives living in the South. The new leadership under Kim Jong-un is much too young to know anything except two Koreas, and have no sentimental attachment to the South. But I also think something more momentous is going on.

*

Communication theorists refer to what they term ‘information noise’: an external input into a communication channel between a sender and a receiver that potentially obscures or makes incomprehensible the signal,or the message. In other words, an increase in ‘noise’ results in a decrease in determinable meaning. There are various categories of such ‘noise’. The North Korean variety in the ‘noise bombing’ is ‘physical noise’, that is, a disturbance or interference coming from an external source that obscures or obstructs the signal. In the case of the balloons, it’s ‘semantic noise’, an interference in the common background or knowledge that makes sharing ideas possible..

But North Korea has weaponized this ‘physical’ and ‘semantic noise’, and by so doing turned it into a kind of information. Paradoxically, the very targeted noisiness of the ‘noise’ becomes a message. It signals that North Korea now assumes there is the total absence of a shared, common cultural background or store of knowledge, and so it is impossible and pointless to freight ‘noise bombing’ with any information in the form of communicable ideas.

The North consciously intends through their latest aggression to show what they think of the South’s propaganda efforts, and to announce the fact that North Korea has given up trying to communicate a message that the receivers, South Koreans, can understand.. However, I think one can argue that unconsciously the North is finally telling us the truth about their own regime. The shit and howling says quite a lot about the sender, because they an inverted expression of what life is really like in North Korea, a nation where communication is effectively entirely devoid of ‘noise’. Everything is organized so that on all levels – physical, physiological, psychological, semantic, cultural, technical, and organizational – the regime can optimally deliver a pure message without ‘noise.’ This is another way of saying that North Korea is a totalitarian state. In a democratic society there is always bound to be ‘noise’ in any communication, especially in a multi-cultural society with multiple senders of messages - a Babel magnified infinitely by the Internet.

*

Sometimes, I’m grateful to North Korea for helping me to see more clearly what’s happening in the world more generally. In this case, their ‘noise-bombing’ and balloon sending has helped me understand President Trump. During his first presidency, Steve Bannon famously coined the motto ‘flood the zone with shit.’ Well, North Korea have inadvertently taken his advice. They are trying to flood the Demilitarized Zone with ‘shit’ – quite literally in some instances. For Bannon was advocating a strategy of maximum communication ‘noise’. You create so much of it that the real messages are rarely received.

So, what is the real message? It looks more and more likely that the real message refer to a coming coup d’etat. The ‘noise’ makes it possible for the coup to happen in slow-motion, so to speak. Without the usual violence, the messiness of storming the Capitol. When will freedom-loving Americans wake up to this increasingly obvious fact? I certainly hope they don’t copy the Germans after they elected Hitler in 1933.

NOTES

The image is a screenshot from:

https://www.euronews.com/2024/10/24/north-korean-balloon-dumps-rubbish-on-south-korean-presidential-compound-a-second-time

For more on ‘information theory’ see: https://www.soundproofcow.com/4-types-of-noise-in-communication/?srsltid=AfmBOorXhkA_oW2-HHLfmkLeVIe-iBH5uXlu6qjjjqfJxbkmyDQDZgEF

https://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1066_Communcation_Theory.pdf

Blue jeans are still subversive (if you live in North Korea)!

More zany news from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Blue jeans are still subversive! Recent evidence of this is the censoring of a British television series about gardening that’s been pirated by the North Koreans to show on state television.

More zany news from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Blue jeans are still subversive over there! Recent evidence of this is the censoring of a British television series about gardening that’s been pirated by the North Koreans to show on state television. The host of ‘Garden Secrets’ is Alan Titchmarsh, who is something of a household name in the UK, and definitely harmless in every way. But when he’s seen wearing jeans, the DPRK censors do that bizarre digital blurring-out effect. This is what it looks like:

For a while a few weeks ago, the BBC had fun reporting the absurdity of this procedure. As the news item put it: “Jeans are seen as a symbol of western imperialism in the secretive state and as such are banned.” Alan Titchmarsh was on record as saying: "It's taken me to reach the age of 74 to be regarded in the same sort of breath as Elvis Presley, Tom Jones, Rod Stewart. You know, wearing trousers that are generally considered by those of us of a sensitive disposition to be rather too tight".

The subliminal message behind the story is clear: those North Koreans are definitely deranged and we (the Brits) are not. In fact, one of the perennial cultural roles of ‘exotic’ places located beyond the British Isles, especially those very far beyond, is to serve as sources of amusement and self-satisfaction for us Brits. The underlying message is usually that the only people with any common sense are us. Elsewhere, people are want to believe in the most silly nonsense, and to behave in ways that are perverse, indecent, childish, dangerous, etc. etc. In this way, the British status quo gets normalized as what’s ‘normal.’ As the public announcement says these days on the UK’s public transport system: ‘If you see something that doesn’t look right, call xxxxxx. See it. Say it. Sorted.’ Evidently, we are all supposed to automatically and unequivocally know what looks ‘right’ is. But how? Because we are habituated to a certain way of thinking and doing things. And for that to be possible, we need to be reminded regularly of the extra-ordinary. Which is where foreigners come in handy.

*

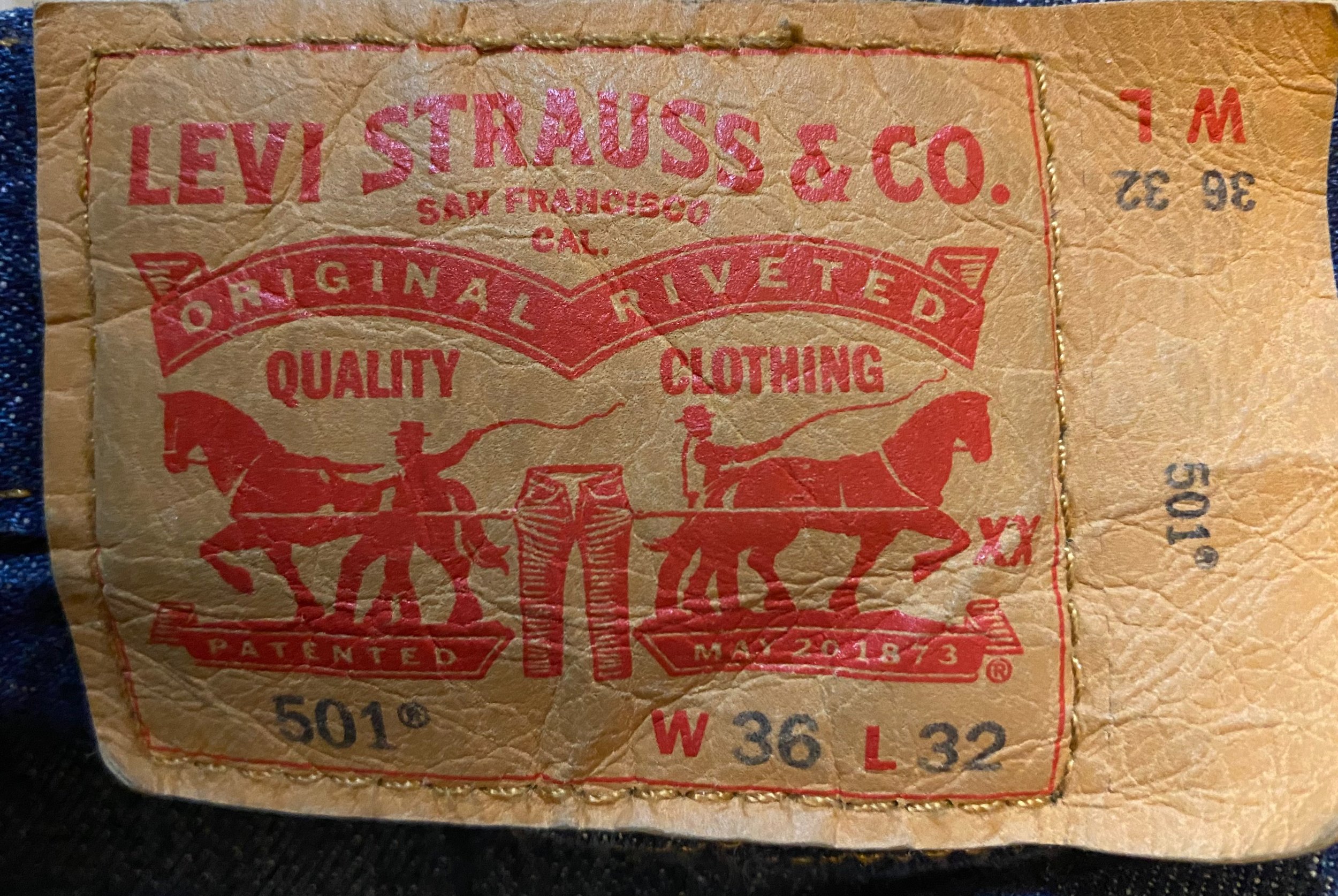

As you almost certainly know, denim jeans were designed in the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States as work wear. The inventor is usually credited as the German immigrant Levi Strauss, who moved to San Francisco during the ‘gold rush’ and patented the innovative design feature of riveted denim in 1873.

By the time I was ready to wear jeans in the late 1960s there were basically three brands on offer: Levis, Wrangler, and Lee, which were all American. As I became fashion conscious in my late teens in the mid-seventies, I decided for some reason (maybe it was something to do with Jack Kerouac and the Beats) that I could only wear Levi 501’s, the original, button fly, shrink-to-fit design (zippers were a standard feature by the mid-1950s). But there was nowhere in my hometown that sold these classic jeans, and so I would make a pilgrimage to nearby Brighton, where there was one shop that reliably stocked them. Once back home, I’d put the cherished (and rather expensive) item on, then lie in the bath watching the indigo dye turn the water blue as the jeans molded themselves nicely to the form of my lower torso and legs (or that was the goal, anyway).

And as they did, it was as if by an act of magical anointing I became part of the great success story. I became part of the American Dream. For while jeans are certainly cheap, comfortable, and hard-wearing, much more was being worn by my younger self than just blue cotton denim. By this time, jeans were a very powerful cultural signifier. What had started out in the west and mid-west of America as hardy workwear for cowboys, lumberjacks, farmers, and construction workers, by mid-twentieth century had morphed into a style icon sought by the young throughout the ‘free’ world. Like Coca-Cola, hamburgers and hotdogs, pop music, and rebellious and sexy youth, jeans came to represent a freer, happier way of life based on the American Dream.

First of all, American GI’s on service overseas – in Germany and during the Korean War and the Vietnam War in the East – wore them on leave, and they became a potent symbol of the new causal look of the Pax Americana. But at the same time, 1950s movies starring Marlon Brando and James Dean made jeans look attractively rebellious, and on Marilyn Monroe they looked sexy. So, jeans became increasingly a symbol of youth rebellion and anti-establishment attitudes. Many US schools in this period banned jeans from being worn by students. By the sixities jeans were what pop stars wore, and anti-Vietnam War protesters, and they were established as one of the most recognizable signifiers of non-conformity, if not of outright depravity. When I put on my blue Levi 501’s, aged sixteen in the provincial England of the mid-1970s, I was unconsciously identifying with the dominant version of ‘success’ within my society.

By the late 1980s you could buy ridiculously expensive ‘designer jeans’. This demonstrates how a symbol of rebellion gets easily co-opted or recuperated by what erstwhile rebellious young people even today (the West, anyway) call ‘the System.’ Jeans where you and I come from are definitely not any danger to civic order. Who knows what brand Alan Titchmarsh was wearing when he shot his gardening series. I bet they weren’t Levi 501’s. Then again, maybe they were…

My mum didn’t like blues jeans, either. I mean, back in the sixities and early seventies she didn’t like me to wear them. We lived in a suburb of a small seaside town, and she insisted I didn’t wear jeans when venturing into the centre of town. But eventually she bowed to the heady winds of cultural change that blew through the early 1970s and gave up on the dress restrictions. I never ever, ever thought I’d be able to draw a straight line between my mum’s sartorial code from back then and those of the DPRK today. But this yet more tragic proof that the DPRK is trapped in a time warp. Its animus against blue jeans belongs to the cultural values of the 1950s, not the present day. It quite simply hasn’t been able to progress beyond an ideological construct from the beginning of the Cold War.

But the DPRK is not alone. What the others so-called ‘rogue’ nations - Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan - have in common with the DPRK is precisely the refusal to westernize, to fail to swim with the seemingly inexorable tide of neoliberal global culturalism. To fall for the ‘American Dream” which has been exported to the ‘free’ world.

It’s worth spending a little time to consider just what this ‘dream’ is (or was). One on-line dictionary says it is “the ideal by which equality of opportunity is available to any American, allowing the highest aspirations and goals to be achieved.” But that seems a bit evasive. The website ‘Investopedia’ cuts to the economic chase: “The American Dream is the belief that anyone can attain their own version of success in a society where upward mobility is possible for everyone.”

But that’s narrowing things too much. From an artistic perspective, the American Dream means success equated with reward for the pursuit of extreme freedom of self-expression, willingness to shock and offend, and to push creativity continuously towards the ‘new’. In fact, these radical values were already part of the modern ‘Western European Dream’, but they were embraced and enhanced when they migrated to the ‘New World’, along with the useful additional assets of economic, military, and political power. Which makes one wonder: just what is ‘success’?

A more critical perspective is need. How about one applying a Marxist interpretation? Here’s something I found on the Internet: “When viewed through the lens of Marxism, the ‘American Dream’ is now more accurately described as a widespread fallacy than a meaningful goal to strive toward.” This quote comes from a very interesting source: a text written in 2023 by a pair of Iraqi academics in the course of writing a critique of Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’ (1949). This play is generally recognized as a searing indictment of the narrowly materialistic version of the ‘you-can-make-it’ ethos of the ‘American Dream’. (Just in passing, recall that, improbably, this same Arthur Miller was married to Marilyn Monroe, which means he could admire her figure in denim jeans at his leisure) The Iraqi academics, Ali Khalaf Othman and Fuad Sahu Khalaf, conclude:

What Willy (Loman, the eponymous ‘salesman’ who commits suicide) seemed to forget or really, judging from his actions, lacked even knowing, and I would go as far as saying, most of the world lack in knowing this next information, is that meritocracy, which is the system that is advertised in America, the system that is so alluring it makes America the land of dreams for refugees, because as long as you work hard enough, you can do anything, right? Well, no, not really. Willy found out the hard way, his family found out the hard way, and I hope, actual people can learn from this play and know before they find out the truth behind the American dream, the hard way.

These authors know what they’re talking about. Iraq is definitely a nation that was offered the ‘American Dream’. In fact it was forced upon them down the barrel of a M14. Disaster followed. Afghanistan is another tragic failure of this ‘dream’. Iran stand as the pioneer of such refusal, when in 1978 it had its Islamic revolution. What’s happening in Gaza and in Ukraine are also in their very different ways versions of the same refusal..

I’m wearing Levi 503’s as I write this post. I’ve given up on the original button-fly model, but the 503’s still have the same classic cut but with a zipper fly (much easier to handle as you get older). I purchased my pair (and lots of other Levi’s clothes, as I have become a walking (and somewhat aged) advertisement for this American icon) at the Levi’s store in the Lotte Outlet in Paju Book City, near where we live. It’s just a stone’s throw from the DMZ. I can imagine a North Korean border guard averting his eyes regularly, as across the narrow Han estuary he glimpses through high-powered binoculars South Koreans of all ages passing lewdly by in denim jeans (including Levi’s, but also, no doubt, ones by Armani).

I’m in absolutely in no doubt where I’d rather be living: somewhere I can were jeans whenever and whenever I like.

And to end, here’s the label from my current pair of Levi 501’s. Subversive stuff, indeed!

NOTES

The photograph at the top of the post is a screen grab from the BBC News website: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-68664644

The dictionary definition is from: https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/

Investopedia quote is from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/american-dream.asp

The essay on ‘Death of a Salesman’ can be found at: https://www.iasj.net/iasj/download/29d6c8a71ed03d4b

Is Kim Jong Un Preparing for War?

I borrow today’s post title from a scary recent article (January 11th) by North Korea experts Robert L. Carlin and Siegfried S. Hecker on the respected website 38 North. In the first paragraph the authors write:: ‘The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950. That may sound overly dramatic, but we believe that, like his grandfather in 1950, Kim Jong Un has made a strategic decision to go to war. We do not know when or how Kim plans to pull the trigger, but the danger is already far beyond the routine warnings in Washington, Seoul and Tokyo about Pyongyang’s “provocations.” In other words, we do not see the war preparation themes in North Korean media appearing since the beginning of last year as typical bluster from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.’

‘Who wants an Americano?’ Ordering coffee, DPRK-style.

Today’s blog title is borrowed from a scary recent article (January 11th) by North Korea experts Robert L. Carlin and Siegfried S. Hecker on the respected website 38 North. In the first paragraph the authors write:

The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950. That may sound overly dramatic, but we believe that, like his grandfather in 1950, Kim Jong Un has made a strategic decision to go to war. We do not know when or how Kim plans to pull the trigger, but the danger is already far beyond the routine warnings in Washington, Seoul and Tokyo about Pyongyang’s “provocations.” In other words, we do not see the war preparation themes in North Korean media appearing since the beginning of last year as typical bluster from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

A key reason for the heightened concern was the 9th Enlarged Plenum of 8th WPK Central Committee, which met in late 2023 (shown in the photograph above). The Rodong Sinmun, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Workers' Party, reporting on the Plenum, announced the following:

For a long period spanning not just ten years but more than half a century, the idea, line and policies for national reunification laid down by our Party and the DPRK government have always roused absolute support and approval of the whole nation and sympathy of the world as they are most just, reasonable and fair. But none of them has brought about a proper fruition and the north-south relations have repeated the vicious cycle of contact and suspension, dialogue and confrontation.

If there is a common point among the "policies toward the north" and "unification policies" pursued by the successive south Korean rulers, it is the "collapse of the DPRK’s regime" and "unification by absorption". And it is clearly proved by the fact that the keynote of "unification under liberal democracy" has been invariably carried forward although the puppet regime has changed more than ten times so far.

The puppet forces’ sinister ambition to destroy our social system and regime has remained unchanged even a bit whether they advocated "democracy" or disguised themselves as "conservatism", the General Secretary [Kim Jong Un] said, and went on:

The general conclusion drawn by our Party, looking back upon the long-standing north-south relations is that reunification can never be achieved with the ROK authorities that defined the "unification by absorption" and "unification under liberal democracy" as their state policy, which is in sharp contradiction with our line of national reunification based on one nation and one state with two systems.

The DPRK claims that as the goal of unification has been made impossible by the United States, and the South is merely its ‘puppet’, there is no point in pursuing it any longer. Since the Plenum, it has therefore formally abandoned unification for the first time. This is the worrying bit for Carlin and Hecker. It does seem to signal a new and dangerous low, especially when seen in the light of recent rapprochement between the two Koreas (and the United States). During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Inter-Korean relations had been gradually improving, despite occasional hickups. In 2000 there was an Inter-Korean Summmit during which the ‘June 15 South-North Joint Declaration’ was adopted. In 2007 another Inter-Korean Summit adopted the ‘Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Relations, Peace and Prosperity’. One tangible sign of this was the construction of the Gaeseong Industrial Complex, which we can see from a local (fortified) hill on a clear day. There, in a bizarre expansion of capitalist entrepreneurial spirit, South Korean companies were permitted to build factories and warehouse and employ cheap North Korean workers. In 2018 two summits in close succession took place, during which Kim Jong Un crossed the border into South Korea and the President of South Korea, Moon Jae-in, successfully brokered the signing of the ‘Panmunjeon Declaration’. This led to an agreement to facilitate further advancements in inter-Korean relations and to establish permanent peace on the peninisula, which included a pledge by the North to aim towards denuclearization via the dismantling of a nuclear test site. There was also the first North Korea-US summit in Singapore with President Trump, who also visited Panmunjeon.

In retrospect, this whole chain of seemingly auspicious events seems to have been little more than an extended publicity campaign on both sides, or more charitably, a case of wishful thinking on the side of the South and the United States. For it seems clear that the North never intended to fulfill its ostensible pledges, or would only do so if the South and the United States went much further than they reasonably could towards ‘normalizing’ relations. For example, ‘denuclearization’ meant very different things for each side.

Over the past five years, North Korea has scrapped the entire agreement. A sign of the souring of relations was the fact that Gaeseong was closed temporarily by South Korea in early 2016 as a response to North Korean missile tests and then immediately permamently shuttered by the North. It’s now a ghost town. North Korean nuclear tests and its development of long-range missiles has grown apace. North Korea is now ignoring telephone calls from South Korea across the multiple Inter-Korean hotlines, which have been a key channel through which to defuse tension.. Key political changes outside the DPRK have also prompted its sea-change; in the South there is now a much more hawkish President who no longer sees any point in being accommodating to Kim Jong Un like his predecessor, and in the United States, Biden has reversed the (ludicrous) ‘buddy’ diplomacy initiated by Trump..

But it seems, fortunately, that not many other NK watchers agree with Carlin and Hecker’s dire, quasi-apocalyptic, warning. As an article posted on BBC online (23rd January) informs us, other experts note that the country is apparently due to reopen to foreign tourists this month, and has also sold so many shells to Russia it is probably not in a strong position to launch a serious attack. Economically, the DPRK’s is a basket case; in 2022 its economy shrank for a third consecutive year, and the nation is classed as one of the poorest countries on earth (the ROK is the 10th largest global economy). Despite the display of fancy weapons during the numerous military parades, and the firing of of expensive missiles into the sea, the numerically huge North Korean army is poorly equipped and would be no match for the South Koreans and their American allies.

The bombastic rhetoric evident in North Korean media is primarily aimed at the domestic audience, and so obviously shouldn’t be taken at face value. If you read Rodong Sinmum’s report on the Plenum one immediately gets the general idea. Here’s an extract from near the beginning of the very long article:

Thanks to the outstanding leadership of our Party and the indomitable efforts of our people intensely loyal to it, precious ideological and spiritual asset was provided to dynamically promote the development of the state in the new era, a scientific guarantee was established to definitely set the goal and direction of the new year’s struggle and accurately attain them and the mightiness and invincibility of our great state were strikingly proved by entities of the rich country with strong army.

In a nutshell, we achieved epochal successes in providing favorable conditions and a solid springboard for further accelerating the future advance in all aspects of socialist construction and the strengthening of the national power through this year’s struggle, not merely passing the third year of the implementation of the five-year plan that we had planned.

Years after the Eighth Party Congress were recorded with unprecedented miracles and changes, but there had been no year full of eye-opening victories and events like this year.

‘Epochal success’! It’s all total bullshit, of course. The disjunct between what is publicly pronounced by the only newspaper of the DPRK’s Workers’ Party and the grim reality is truly mind-bending, or gut wrenching.

*

Since the end of the Korean War, the term ‘unification’ has always been ambiguous. “Unified’ under which of the diametrically opposite systems? The Korean War began when the North invaded the South with the goal of unifying Korea by force. This has always remained its intention, despite claims to the contrary. Kim Jong Un says as much by protection his regime’s intentions onto the Republic of Korea by claiming its goal is “unification under liberal democracy.” But, actually, he’s right. How else could real unification happen except through political as well as economic union?

No one I’ve talked to in the South over the years – people of all ages – believe unification is a real option. It has long been a fiction neither side really believes in. It’s said that if the North’s regime collapsed and the South took over, like West Germany which absorbed communist East Germany after the end of the Cold War, it would swiftly bankrupt the South. The economic disparity between the two Koreas is far, far greater than between the two Germanys. But so too are the social disparities; South Korea has the fastest broadband connection in the world while North Korea doesn’t even have the Internet (for reasons of social control).

One prosaic reason for the North Korean announcement having less visceral impact than it would once have had is the fact that very few Koreans on either side of the DMZ remember a time when the Korean peninsula actually was united., and if they do, it was because it was a Japanese colony not an independent nation. Many of the graves around where we live are for Koreans born in the North who wanted to buried within sight of their homeland. My wife’s father escaped from Pyeongyang as a young man, fought in the Korean War, married a South Korea and never learned what happened to the family he left behind. Before his death, he tried and failed to find relatives during the family reunions organized since 1985 – the last one was in 2018. These reunions wer part-and-parcel of the thawing of animosity between the two Koreas. For his generation, the loss of ‘unity’ was felt as a very personal level. But Kim Jong Un was born in 1984, and so he has no direct experience of a time when there was one united Korea, nor do most North and South Koreans today.

*

In the United States it is also seems that, most obviously for MAGA supporters and QAnon conspiracy theorists, facts are of little importance in framing public and private discourse,. But at least there are alternative narratives within the reach of every citizen. But in North Korea there is just the one narrative. All any North Korean citizen knows is the fairy story the Party tells. Which is why the punishments for accessing alternative narratives, via South Korean tv show and music, for example, is punished severely, and there is no Internet. Human Rights Watch’s report for 2023 writes:

The North Korean government does not permit freedom of thought, opinion, expression, or information. All media is strictly controlled. Accessing phones, computers, televisions, radios, or media content that is not sanctioned by the government is illegal and considered “anti-socialist behavior” to be severely punished. The government regularly cracks down on those viewing or accessing unsanctioned media. It also jams Chinese mobile phone services at the border, and targets for arrest those communicating with people outside of the country or connecting outsiders to people inside the country.

But the disturbing fact is that even in a country that enshrines freedom of speech in its constitution, people often seem more content when there is only one story to choose from. Anxiety and insecurity (and therefore the potential for change and self-transformation) come when doubt sets in and one questions what one hears and sees. Such doubts are a direct result of encountering alternatives and having to make choices. But the unprecedented access to information made possible thanks to the Internet has not led people to become more open to and comfortable with different narratives. Instead, it often makes them even more insecure. They are overwhelmed by a tsunami of varied and often contradictory narratives, and in defense are inclined to withdraw into ‘siloed’ information zones.. They wrap themselves beneath a comfort blanket comprised only of what conforms to the narrative which makes them feel secure..

Amazingly, it seems a fairy story can trump lived reality. Or, lived reality is all too often experienced through the fairy story. This is sobering evidence of the extent to which we humans exist not primarily in relation to the direct input coming ‘bottom up’ from our senses but to our ‘top down’ memories, prior knowledge, and social conditioning.. Understandably, we all crave certainty, and the role played by often uncomfortable, unfamiliar, or complicated facts in furnishing this state is, so it seems, only marginal.

*

And finally, to return to the likelihood of war here on the Korean peninsula, but also, potentially, on a much bigger scale..

As the authors of the 38 North article point out, it’s possible that North Korea will engage in some kind of specific provocation, like when they shelled Yeonpyeong island or sank the ROK navy ship Cheonan in 2010. But as they also write, mad as it may seem, the regime could now be seriously contemplating a tactical nuclear strike. They remind us that ‘North Korea has a large nuclear arsenal, by our estimate of potentially 50 or 60 warheads deliverable on missiles that can reach all of South Korea, virtually all of Japan (including Okinawa) and Guam. If, as we suspect, Kim has convinced himself that after decades of trying, there is no way to engage the United States, his recent words and actions point toward the prospects of a military solution using that arsenal.’

Oh, dear.

Then again, Kim Jong Un and his cronies surely know that a nuclear strike would be signing their own death warrants, even if they have very deep shelters to hide in. They are not a death cult like Hamas and the Jihadists. They do not believe in Paradise. At least, not in one that transcends this world and awaits them when they die a martyr’s death. Kim and Co. already have their ‘paradise’ on Earth. It’s called the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and you can read all about it in the Rodong Sinmun.

NOTES

The image is sourced from: https://m.en.freshnewsasia.com/index.php/en/localnews/44185-2024-01-03-03-18-17.html

The 38 North article can be read at: https://www.38north.org/2024/01/is-kim-jong-un-preparing-for-war/

The BBC article is at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-68052515

The Human Rights Watch data is at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/north-korea

The Rodong Sinmun article, ‘ Report on 9th Enlarged Plenum of 8th WPK Central Committee’, is available at:

The end of the year (or one of them)

Some thoughts on the end of the (or a) year in South Korea, and the bizarre calendar adopted by my neighbors north of the DMZ.

North Korea’s Juche calendar for 2010.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juche_calendar#/media/File:North_Korea_(5015886634).jpg

It's interesting to consider the similarities and differences between South Korean and British attitudes to the Christmas holiday that has just passed. As in my homeland, some Koreans will have celebrated it as a religious occasion, going to church and so on. After all, 28% are now Christian. Nevertheless, I’m sure even the faithful are likely to have embraced the event for what it now truly is: a celebration of consumer capitalism. But one of the great solaces of living here is that Christmas is a far less gaudy obstacle to surmount than it is back home. One has to endure the usual execrable Christmas-themed pop music in all the cafes, but life does not ground to a halt under the weight of Santa and his toy-and-commodity laden sleigh as it does in Great Britain.

*

I’m living in a country when there are two New Year’s day each year.The latter is approaching fast, while the former isn’t until what in the former’s calendar is called February 10th. But last year it was on 22nd January. This is because the traditional Korean calendar is ‘lunisolar’, that is, calculated in relation to the cycles of the moon not the sun.

It used to be that way in Europe too. The shift in the arrangement of time away from the moon to bring it closer to the more regular cycle of the solar year occurred under the Roman Empire in 46BC when it was mandated by Julius Caesar – hence its name, the ‘Julian Calendar’. In 1582, the “Gregorian Calendar’, named after Pope Gregory XIII, was introduced. This is still the one we use today. (The main change was in the spacing of leap years to make the average calendar year 365.2425 days long, which even more closely approximates the 365.2422-day of the ‘solar’ year.) But it wasn’t until as recently 1752 that the beginning of the year was officially moved from March 1st to January 1st.

All this history pertains, of course, to Europe alone, or at least it used to. Pre-globalization, in pre-modern Korea as in the other Chinese influenced countries of East Asia, a lunisolar calendar was traditionally employed called the Dangun calendar. In South Korea, this still remains the basis on which the dates of holidays and commemorative events are calculated, such as the Buddha’s birthday and Chuseok. So, South Koreans essentially live according to two significantly different systems for organizing the passage of time over the course of a year. Like so much else, this reflects the nation’s efforts to absorb Western culture while maintaining ties with indigenous and regional tradition.

*

Also note that the universally agreed-upon conventions for calculating when to begin counting the years is welded solidly to Christianity. It’s 2024 next year because Jesus Christ was born 2024 years ago according to the Gregorian calendar. Hence the fact that the convention is to date events as BC – ‘Before Christ’ – and AD – ‘Anno domini.’ This means that every time we use the normal system for structuring time, we are tacitly placing the Christian religion at the centre of our timekeeping. Critical awareness of this rather obvious bias is why we are now inclined to write BCE – ‘Before the Christian Era’ – and ‘CE’ – “Christian Era.’ But this subtle shift in nomenclature only very marginally decenters Christianity.

Whoever controls the measuring and naming of time, controls society, which is why those in a hurry to change it, also change the calendar. After the French Revolution of 1789 AD (in the Gregorian calendar) a ‘Republican Calendar’ was adopted, the aim of which was to liberate the citizens of France from tutelage to the timekeeping of the royalist Ancien régime and the bane of Christian religion. But such was the chaos of the times that the leadership could never agree when Year 1 actually began, and so it was regularly amended! Once a convention as practical and vital for social interaction as the calendar is deep-rooted it proves impossible to uproot. Imagine the confusion if, say, the critical race theorists or another so-called ‘wokeist’ factions sought to shift the organization of the calendar to better reflect their pressing concerns.

It was in a similar attempt to forge an independent and ideologically controllable timekeeping system that in 1997 North Korea adopted a calendar known as the Juche calendar. Year-numbering begins with the birth of the first leader, Kim Il Sung, which is 1912 in the Gregorian calendar, and so is called Juche 1 in the Juche calendar. This means that by my calculation we’re now living in Juche 123, and soon will be in Juche 124, although not until April 15th, Kim’s birthday. The DPRK, at least officially, has therefore abandoned both the traditional lunisolar and the Western solar calendars. But in practice, there are 3 New Years every year, as North Koreans apparently recognize the Western New Year, the Lunar New Year, and the Juche New Year. This seems rather greedy. But whichever New Year it is they all begin with the same obligation: you must first lay flowers at the bronze statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il at Mansudae Grand Monuments in Pyongyang, and statues sited elsewhere throughout the nation.

We can assume with some certainty that the hope for a brighter or better New Year, according to all three calendars, is extremely slim for the children of today’s average North Korean parents, or even those of the elite. However, through adopting a perverse version of historical consciousness that flattens the past to the mere dozens of years since 1912, the regime instills in the people a model of history in which the Kim ‘dynasty’ assumes absolute power over past, present, and future. The goal is to delude them into believing that their children’s better and brighter future is guaranteed – but only if they accept repression by the current regime. For someone to actually believe this brutal canard must require an extraordinary level of cognitive dissonance. But probably only as elevated as the dissonance required for an American to believe Donald Trump should be the next President of the United States!

NOTES

For more on celebrating New Year (or Years) in North Korea, visit: https://www.uritours.com/blog/north-koreans-celebrate-new-years-3-times-in-one-year/

Boundaries, terrestrial and extra-terrestrial

Recently, North Korea boasted that it had successfully launched a spy satellite into orbit. In this post I reflect on very different kinds of boundary.

A screen grab from the Guardian on-line (November 28th). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/28/north-korea-claims-spy-satellite-has-photographed-white-house-and-pentagon

Recently, North Korea boasted that it had successfully launched a spy satellite into orbit. The Guardian newspaper on-line (November 28th) reports that it has ‘sent back “detailed” images of the White House, the Pentagon and US nuclear aircraft carriers that have been viewed by the regime leader, Kim Jong-un.’ The Guardian published the photograph at the top of today’s post. Hilarious, isn’t it? The T-shirts sported by the science wonks are priceless. I want one! I imagine the piece of paper they’re holding shows Scarlett Johansson sunbathing beside her pool in her USD 3.88 million home in Los Feliz, recorded while the satellite was passing over Los Angeles.

It would be comic, except the news has now brought us one step closer to war. Again. Life near the DMZ has just gotten fractionally more insecure. Am I just imagining it, or are there more live fire-drills taking place? More troop movements? It may be a ruse. After all, they have already failed twice. But the suspicion is that Russia has recently provided much needed technological support, and in return, North Korea is providing Russia with thousands of artillery shells. What a diabolical marriage made in Hell!

*

I was struck by the chance juxtaposition in the media of this advanced extra-terrestrial surveillance technology with what’s currently going on in Israel/Palestine: the contrast between two relationships to the world - between attaching oneself to a particular patch of soil and having panoptic access to the entire world.

In Israel/Palestine what we see playing out in terrible detail via the media is a crisis brought on by a fundamental human orientation to land and territory. Strife and war between humans have historically always been about appropriation of land. A sense of being at home in a particular place is axiomatic. The securing of a particular area of land through migration, colonization, and conquest leads to the setting up of social order and the organization of economic life of society. Only by dwelling somewhere do we feel truly human. This also meant that because societies are historically grounded in the occupation of a particular area of land, the construction of boundaries is absolutely necessary.

So, what is happening in Israel/Palestine is an ancient struggle for the appropriation of land, one that in spite of all the huge changes that have occurred over the past one hundred years remains central to human meaningful existence. Two peoples claim the same land as their own.

And yet, at the same time, thanks to globalization, a thoroughgoing deterritorialization of human existence has occurred. In fact, this process began long before the period usually described as ‘modern’. The uniquely iintimate link between being human and dwelling on the land was destroyed over 500 years ago when the oceans were systematically opened up. From this point onwards, human society ceased being land-based and lost its status as the connection to specific area of the Earth. Humans were no longer earth-bound. With the development of maritime technology - improved ship construction, the invention of the compass, the science of mapping - Europeans spearheaded the subjection of the entire planet to appropriation and control which had begun millennia before. when humans first developed boats that could carry them across the oceans. The general assumption became that by the end of the twentieth century, globalization meant the struggle between humans for the appropriation of land was over. Humanity had spread all over the entire globe, across land, sea, and space, and there was nowhere else to go.

The North Korean’s launching of a spy satellite is in line with the logic of modernity in this sense. It is part-and-parcel of the process through which humanity has detached itself from its terrestrial bonds and manufactured a god-like view which bestows upon it immense power. It is this technologically-assisted extension of human perception that dominates our experience of the world – at least those of us who live in the developed world, and those who seek to maintain their security in relation to this world – nations like North Korea, for example. To ensure a secure boundary for appropriated land entails the production of technologies that will deter others from making a grab for it. In this sense, the spy satellite is a contemporary standard form of boundary establishment generated on a global rather than terrestrial scale.

Meanwhile, in Israel/Palestine boundaries of a more ancient kind were erected. Israel constructed a fence to pen in the Gaza Palestinians. But this fence proved catastrophically inadequate. This was not because of sophisticated technological subversion, however, but rather because of the violent invasion of land by humans.

In this sense, the conflict in Israel/Palestine brings together the pre-modern and modern, the post-terrestrial and the terrestrial. Israel’s folly has been to attempt to live like a globalized nation in a region that is still trapped in a feud over land, trapped in a way of dwelling on earth - of being human - that is ancient, and has been kept alive through the bungling of modern leaders.

*

But however awful the conflict in Israel /Palestine is, in a weird sense it is actually reassuring on a certain level, in the sense that it is enacting a very familiar kind of struggle over the appropriation of land based on historical precedent, religious justification, and political compromises. With climate change, the conflict between the global and the local will become even more tense. It is transforming the land upon which people dwell, forcing many of them to migrate and causing perpetual conflicts over dwelling rights. We will be seeing lots more violent struggles over land use because of the pressures of climate change, but they won’t be rooted in evident history like the one in Israel/Palestine.

As Bruno Latour writes in Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime, , in order to effectively confront climate change we need “to be able to succeed in carrying out two complementary movements that the ordeal of modernization has made contradictory: attaching oneself to a particular patch of soil on the one hand, having access to the global world on the other. Up to now…. such an operation has been considered impossible: between the two, it is said, one has to choose. It is this apparent contradiction that current history may be bringing to an end.’

NOTES

The Guardian article can be accessed at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/28/north-korea-claims-spy-satellite-has-photographed-white-house-and-pentagon

The Bruno Latour quote is from Down To Earth. Poltics in the New Climatic Regime (Polity, 2018), p.12

A view of the North

I recently visited Ganghwado Jejeokbong Peace Observatory, which is in the northern area of the Civilian Restricted Zone that abuts the DMZ. From the observatory, you can see the Democratic People’s Republic just 2 km way across the estuary.

North Korea seen from the Ganghwa Peace Observatory..

I recently visited Ganghwado Jejeokbong Peace Observatory, which is in the northern area of the Civilian Restricted Zone that abuts the DMZ. From the observatory, you can see the Democratic People’s Republic just 2 km way across the estuary.

The Observatory entrance.

A guide gives a talk in front of a model of the area.

Ganghwa is an island, and not far from where I live. But as you can see from this map it’s necessary to take a sizeable detour via Gimpo due to the restrictions imposed by the DMZ. The blue pointer is the location of the Observatory and the X is where we live. The dotted line is the border. Note how close this is to Seoul!

There was quite a lot of fighting around Ganghwado during the Korean War, but there’s also an interesting back story, linking it to an earlier violent period, and one that serves to put things in a wider historical context.

Determined to force the Korean government to end its isolationism, an armed American merchant schooner named the SS General Sherman sailed for Korea in 1866. The owner was hoping to open Joseon to trade, just as another American, Commodore Perry, had successfully done in Japan in 1853. But the crew outraged the locals, forcibly breaching the promulgation made by the government that forbade any contact with foreigners. The crew where murdered and the ship caught fire and sank after it sailed into the Taedong River which flows through Pyongyang.

In 1871 the so-called United States Expedition to Korea was initiated with the intention of finding out what had happened to the Sherman and to make a show of strength that would force Joseon into ending its ‘closed doors’ policy. The ‘show of strength’ was made predominantly on and around Ganghwa Island. The American stormed the fortresses there, and in the end over 200 Korean Soldiers were killed. But if the United States had hoped this show of military muscle would persuade the Koreans, it totally failed. The governed refused to negotiate and even strengthened the policy of isolation.

But the writing was on the wall. In fact, it was Japan that sealed Joseon’s fate. In 1868 the Meiji government had asked for diplomatic relations with Joseon, which were rejected. Like the United States, Japan then staged in 1875 an armed protest using a warship , and then pressed the kingdom to open its ports. The Treaty of Ganghwa was signed in February 1876. By 1905 Japan had deprived Joseon of its diplomatic sovereignty and made it protectorate. In 1910 it was annexed and became a colony. This tutelage endured until imperial Japan’s defeat in 1945.

American servicemen stand atop one of the forts on Ganghwa Island after its capture. 1871.

Not surprising, the North Korean regime milks the propaganda value of the sinking of the General Sherman, holding rallies in front of a monument dedicated to the killing of Americans and the ship’s sinking. The monument is close to where the USS Pueblo is anchored - the U.S. Navy intelligence ship captured while in the East Sea in January 1968.

*

I have to say North Korea looked rather bucolic from the Ganghwa Observatory. Very unspoilt. Through a telescope you can even zoom in on farmers working in the fields and soldiers on patrol. Perhaps because I’d recently been stuck in horrendous traffic near Seoul and obliged to drive at a snail’s pace along a polluted highways flanked by rank upon rank of ugly tower blocks, I was struck by a huge irony.

Ecologically speaking, North Korea’s carbon footprint is tiny compared to its competitor to the south. Carbon dioxide emissions are estimated to be about 56.38 million metric tons in 2021 in North Korea. Its GHG emissions peaked in the early 1990s, and according to UN statistics, have declined by roughly 70% since 1993. As a result, North Korean CO2 emissions account for only 0.15% of global emissions. In 2020, the greenhouse gases emitted in South Korea totalled 656.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. An average person produces 13.5 tons of greenhouse gases per year.

What does this suggest? Is a totalitarian regime that brutally curbs the freedom of its populace, and due to basic energy shortages is obliged to turn off the lights at night, the kind of state best styled to ensure we reach the target of Net Zero in 2030? Is North Korea a role-model for balancing greenhouse gases going into the atmosphere by removing them from the atmosphere?

Of course not! What the view from the observatory does not show us the fact that North Korea is suffering total environmental collapse. An obvious sign of this is the contrast between the densely wooded hills in the South and the barren one’s you can see across the DMZ.

The following is an account of a visit made by Western scientists back in 2013 when it was still possible to go there:

‘When ecologist Margaret Palmer visited North Korea, she didn’t know what to expect, but what she saw was beyond belief. From river’s edge to the tops of hills, the entire landscape was lifeless and barren. Villages were little more than hastily constructed shantytowns where residents wore camouflage netting, presumably in preparation for a foreign invasion they feared to be imminent. Emaciated looking farmers tilled the earth with plows pulled by oxen and trudged through half-frozen streams to collect nutrient-rich sediments for their fields. “We went to a national park where we saw maybe one or two birds, but other than that you don’t see any wildlife,” Palmer says.

“The landscape is just basically dead,” adds Dutch soil scientist Joris van der Kamp. “It’s a difficult condition to live in, to survive.”

Palmer and Van der Kamp were part of an international delegation of scientists invited by the government of North Korea and funded by the American Association for the Advancement of Science to attend a recent conference on ecological restoration in the long-isolated country. Through site visits and presentations by North Korean scientists they witnessed a barren landscape that is teetering on collapse, ravaged by decades of environmental degradation.

“There are no branches of trees on the ground,” Van der Kamp says. “Everything is collected for food or fuel or animal food, almost nothing is left for the soil. We saw people mining clay material from the rivers in areas that had been polished by ice and warming their hands along the roadside by small fires from the small amounts of organic bits they could find.

Since 2013 things have only gotten worse., North Korea has seen its longest drought and rainy seasons in over a century. Kim Jong Un and his cronies make appropriate noises, calling for immediate steps to counteract the impact of climate change. But it’s hopeless. After all, they spend all their money on armaments.

Which is to all just to say that appearances can be deceptive. I hate the way South Korea’s race to become a modern ‘developed’ capitalist nation has devastated the country’s environment, brutally slicing it up with highways and herding people into tower block ghettos. But I’m certainly glad I live here rather than across that 2 km stretch of water that laps against Ganghwa island.

NOTES

The archive photo from 1871 is from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_expedition_to_Korea#/media/File:Ganghwa_3-edit.jpg

The quote is from: ‘Inside North Korea's Environmental Collapse. Scientists who recently visited the hermit nation report the situation is dire’, by Philip McKenna. Nova. March 7, 2013, available at:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/inside-north-koreas-environmental-collapse/

‘A Nation of Racist Dwarfs’

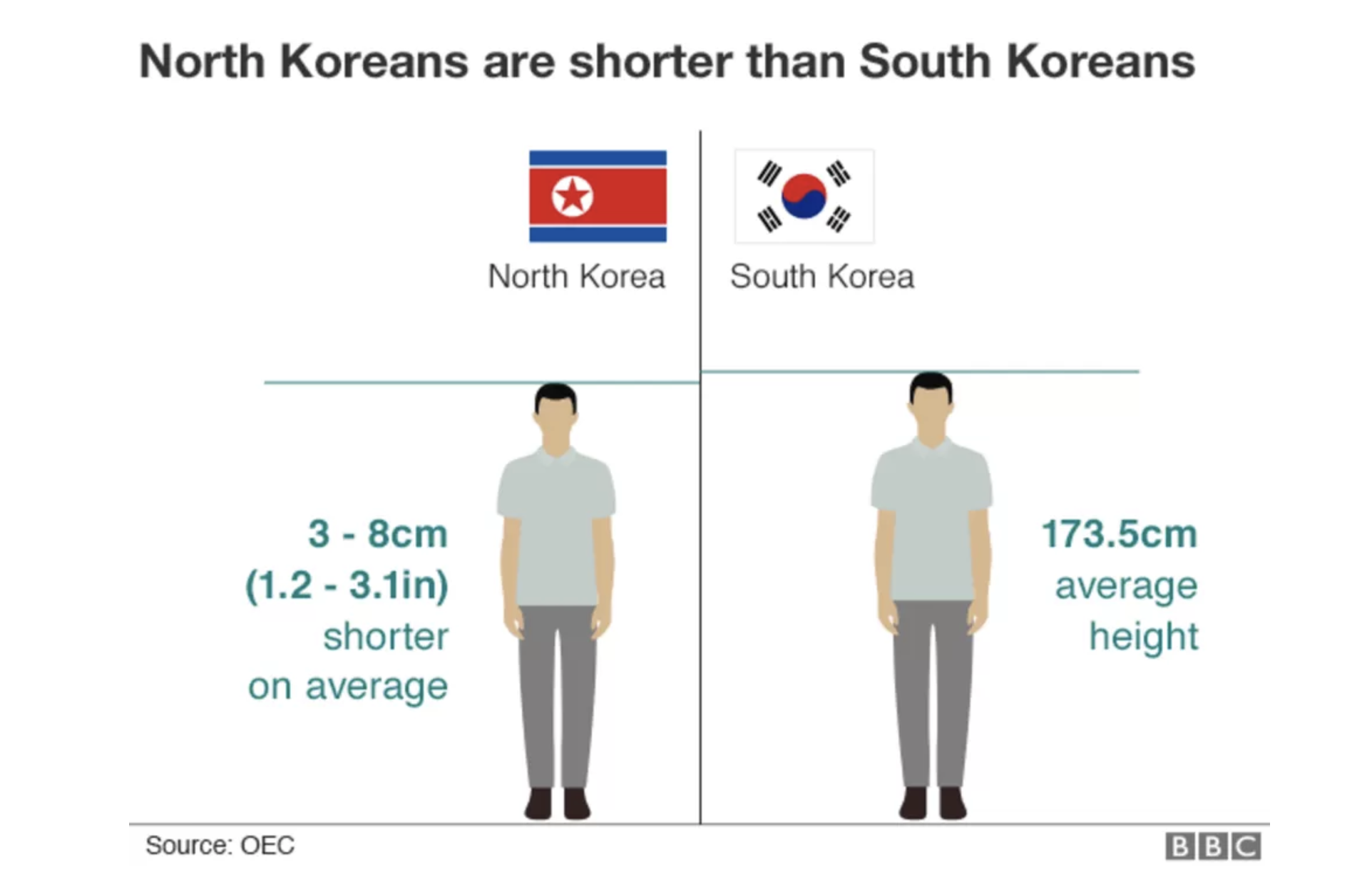

The title of today’s post is lifted from Christopher Hitchens’ essay from 2010 which I mentioned in my previous blog. Catchy isn’t it? And not a little racist, which is rather rich in that The Hitch makes a special point of describing North Korean as racist and xenophobic. He writes with authority that “a North Korean is on average six inches shorter than a South Korean”. But it’s not true! well, he was exaggerating. Find out how much.

The title of today’s post is lifted from Christopher Hitchens’ essay from 2010 which I mentioned in my previous blog. Catchy isn’t it? And not a little racist, which is rather rich in that The Hitch makes a special point of describing North Korean as racist and xenophobic. He writes with authority that “a North Korean is on average six inches shorter than a South Korean”, and goes on to invite us “to imagine how much surplus value has been wrung out of such a slave, and for how long, in order to feed and sustain the militarized crime family that completely owns both the country and its people.”

This data is shocking because while North Koreans got shorter, South Koreans got taller. But six inches (15.24 centimeters)? Are North Koreans (Hitchens doesn’t specify if he refers to a male or female) really that much shorter? The simple answer is no.

They are defintely shorter, but not nearly so much as Hitchens specifies. In 2002, the South Korean Research Institute of Standard and Science used United Nations survey data collected inside North Korea, and found that pre-school children raised in North Korea were up to 13 cm (5.1 inches) shorter and up to 7 kg lighter than children brought up in South Korea. Commentators put this down to the famine of the 1990s, which left one in every three children in North Korea chronically malnourished or 'stunted'. In 2006, the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention surveyed the physical condition of 1,075 North Korean defectors ranging in age from 20 to 39, and found that the average height of North Korean males was 165.6 centimeters (5 feet 5 inches), and North Korean females 154.9 centimeters (5 feet 1 inches). By comparison, an average South Korean man was 172.5 centimeters (5 feet six inches) tall and a woman 159.1 centimeters (5 feet 2.5 inches). The cause was clear: North Korea suffered from food shortages and the collapse of its public health and medical care system. In an essay from 2009 Professor Daniel Schwekendiek from Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul stated that North Korean adult men are, on average, between 3 to 8cm (1.2 to 3.1 inches) shorter than their South Korean counterparts. This is also the data on the BBC website (illustrated above) which says South Korean men are an average of 173.5 centimeters tall, and North Koreans are 3 to 8 centimeters shorter. But the most recent data I could find, at Wisevoter.com, puts the North Korean at 175 cm and a South Korean at 176cm. Just one centimeter apart! So, I really don’t know what the exact difference is!

So Hitchens was definitely exaggerating. But nevertheless, the height difference between North and South Korea is real and can only be put down to one thing: the political systems. In effect, the Korean peninsula is a tragic experiment in the impact on culture of biology.

This is what is called ‘epigenetic change’, which refers to environmental factors that impact on the human genome. The DNA sequence does not change but the organism's observable traits are modified. These epigenetic factors are typically described as external agents like heavy metals, pesticides, diesel exhaust, tobacco smoke, hormones, radioactivity, viruses and bacteria, or lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, stress, and sleep. One can also add political systems whose policies directly impact on what, how, when, and which people eat, what kind of medical care they receive, and what environmental agents people are or are not exposed to.

All these factors influence the expression of some genes, both positively and negatively. In the case of North Korea, mostly negatively. The variation of hieght is therefore graphic evidence on the most basic level of the regime’s abject failure. Maybe North Koreans are not ‘racist dwarfs’, but they certainly have paid a terrible physical price so that a vile clique can cling onto power.

To put the Korean statistics in perspective, here is some more data: an adult man in the UK is 178 cm average height, in the USA is 178 cm, and in France is 179cm (yes! taller on average that the Brits, which was shocking news to me, at least). The tallest human males in the world are Dutchmen at 184cm - an average 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) bigger than North Koreans.

*

Over the past two hundred years almost everyone in the world has been getting taller thanks to a better diet and medical care. As in Europe before the modern period, during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) Koreans adults were significantly shorter on average than today’s Koreans - Northern and Southern. According to the first nationwide study into the height of Koreans, including Joseon era Koreans, average heights of both male have increased by 12.9 centimeters (5 inches) and female adults by 11.6 centimeters (4.5 inches) over the past century.

But just as on the Korean peninsular today, history also shows that the trajectory is not always continuously upwards. Here’s something interesting I found while surfing for this post at OSU.edu: Northern European men had actually lost an average of 6.3 centimeters (2.5 inches) of height by the 1700s , and this loss that was not fully recovered until the first half of the 20th century!

A variety of factors contributed to the drop – and subsequent regain – in average height during the last millennium. These factors include climate change; the growth of cities and the resulting spread of communicable diseases; changes in political structures; and changes in agricultural production.

"Average height is a good way to measure the availability and consumption of basic necessities such as food, clothing, shelter, medical care and exposure to disease," [Richard] Steckel said. "Height is also sensitive to the degree of inequality between populations."

"These brief periods of warming disguised the long-term trend of cooler temperatures, so people were less likely to move to warmer regions and were more likely to stick with traditional farming methods that ultimately failed," he said. "Climate change was likely to have imposed serious economic and health costs on northern Europeans, which in turn may have caused a downward trend in average height."

Urbanization and the growth of trade gained considerable momentum in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Both brought people together, which encouraged the spread of disease. And global exploration and trade led to the worldwide diffusion of many diseases into previously isolated areas.

"Height studies for the late 18th and early 19th centuries show that large cities were particularly hazardous for health," Steckel said. "Urban centers were reservoirs for the spread of communicable diseases."

Inequality in Europe grew considerably during the 16th century and stayed high until the 20th century – the rich grew richer from soaring land rents while the poor paid higher prices for food, housing and land.

"In poor countries, or among the poor in moderate-income nations, large numbers of people are biologically stressed or deprived, which can lead to stunted growth," Steckel said. "It's plausible that growing inequality could have increased stress in ways that reduced average heights in the centuries immediately following the Middle Ages."

Political changes and strife also brought people together as well as put demand on resources.

"Wars decreased population density, which could be credited with improving health, but at a large cost of disrupting production and spreading disease," Steckel said. "Also, urbanization and inequality put increasing pressure on resources, which may have helped lead to a smaller stature."

Exactly why average height began to increase during the 18th and 19th centuries isn't completely clear, but Steckel surmises that climate change as well as improvements in agriculture helped.

"Increased height may have been due partly to the retreat of the Little Ice Age, which would have contributed to higher yields in agriculture. Also, improvements in agricultural productivity that began in the 18th century made food more plentiful to more people.

And here to finish are some famous people’s heights:

Bonaparte = 168cm.

Hitler = 174 cm.

Kim Jong-eun = 168.9 cm.

Putin = 169cm.

Trump = 184cm.

Interestingly, Hitchens (who died in 2011) was 175 cm tall,. That is, the same height as an average North Korean male today.

NOTES

The image at the start of this post is from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41228181

Christopher Hitchens article is at: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2010/02/kim-jong-il-s-regime-is-even-weirder-and-more-despicable-than-you-thought.html

Daniel Schwekendiek essay is at: ttps://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-biosocial-science/article/abs/height-and-weight-differences-between-north-and-south-korea/2EED5360F62997E3007425258C04A45A

The epigentics diagram is from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41440-019-0248-0

The data about Joseon era average heights is from: https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20120131000667

The quotation about average heights in Europe over the past three hundred years is at: https://news.osu.edu/men-from-early-middle-ages-were-nearly-as-tall-as-modern-people/

My list of famous people’s heights is from: https://www.celebheights.com/s/Kim-Jong-Un-49758.html

Wisevoter.com data is at: https://wisevoter.com/country-rankings/average-height-by-country/

‘North Korea: ‘a phenomenon of the very extreme and pathological right.’

The title of the post is a quotation from the British writer Christopher Hitchens, who wrote about the North Korean system in an article written in 2010. Hitchens began by recounting a visit to North Korea and how his minder had expressed racist views in such a way that it was obvious that such views were central to what, for him, was a quite normal and acceptable worldview. I think about how to understand this dreadful ideology within a wider context.

This photograph (not taken by me, although I’ve been there) shows North Korean border guards strutting their stuff just a few miles from where I’m writing this post, at Panmunjom, the only place where the DMZ narrows and the two Koreas meet. The title of today’s post is a quotation from the British writer Christopher Hitchens, who in 2010 wrote about the North Korean system in a much commented upon article. Hitchens began by recounting a visit to North Korea and how his minder had expressed racist views in such a way that it was obvious that these views were central to what for him was a quite normal and acceptable worldview. But his article was specifically motivated by reading the then recently published book by B. R. Myers entitled ‘The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters’. As Hitchens wrote, Myers described “the Kim Jong-il system as a phenomenon of the very extreme and pathological right. It is based on totalitarian ‘military first’ mobilization, is maintained by slave labour, and instills an ideology of the most unapologetic racism and xenophobia.“

Since then, under Kim Jong-Ill’s successor, his son Kim Jong Un, things have only gotten worse in the DPRK, and many analysts would agree with Myers’ general prognosis. For example, it seems obvious that to persist in describing the country as ‘communist’ is very misleading, not least because the DPRK itself doesn’t use the word anymore! Ideologically, it prefers to refers to ‘Juche’ thought, which is usually translated as ‘self-reliance’ and is intended to be a specifically North Korean ideology - the one Myers’ set about describing. But it is interesting to consider how the term ‘communist’ was initially adopted and then discarded in the DPRK.

The North Korean regime was put in place by the Soviet Union, whose forces occupied the northern part of the peninsula at the end of World War Two. The first of the Kim dynasty, the former guerrilla fighter in China Kim Il-sung, was installed by Stalin as a counterpoint to the American candidate in the south, Syngman Rhee. This is an archive photograph from 1946 of people in Pyongyang parading with portraits of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Kim Il Sung:

Subsequently, two rival Koreans came into being in 1948. In 1950, Stalin gave Kim the ‘green light’ to invade the Republic of Korea. By that time, China had also fallen to the Communists. After the failure of the invasion and the stalemate of the Korean War, the DPRK settled into being a client state of the Soviet Union (and to a lesser extent, China) until the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the abandonment of communism in Russia precipitated a humanitarian and ideological crisis in the DPRK. But by that time the country had already moved to established its own distinctly ‘Korean’ ideology of Juche. It is this ideology that Hitchens characterised as being on the far ‘right’ politically because its racist and xenophobic traits are not ones that could be associated with the far ‘’left’.

But to what extent is this ‘left’/’right’ polarity an accurate way of analyzing the reality of North Korea over the past thirty years?

*

Following the French Revolution in 1789, when members of the National Assembly divided into supporters of the old order sat to the president's right and those of the revolution to the left, it became customary in the West (and then internationally) to described politics in terms of ‘left’ and ‘right’. In the nineteenth century Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels described ‘communism’ ’as a radical politics of the ‘left’ that recognized the historical inevitability of class war within capitalist societies leading to a revolution after which all property would be publicly owned and each person’s labour paid for according to ability and needs. It was therefore specifically cast as the antithesis to the ‘right-wing’ ideologies of the industrailized capitalist societies in which property was privately owned and labour rewarded unevenly and in relation to entrenched inequalities rooted in class and race. ‘Communism’ thus became the portmanteau term of the twentieth century for ‘leftist’ radical politics directed towards revolution from below, which, after the Bolshevik revolution in Russia 1917, was monopolized by the Soviet Communist Party.

But for post-colonial Korea, ‘communism’ meant something very different. It involved adopting one of the only two route maps towards modernization provided by the globally dominant West. Under the guidance of the United States the Republic of Korea had chosen the capitalist map, while the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea chose the communist one. It should be noted that neither map included democracy in Korea at this initial stage.

In relation to the communist road map, it is important to consider that Korea was also very far from being an industrialized economy against which a Korean ‘proletariat’ (the actually almost non-existent factory workers) - could be seen to be struggling for freedom against their capitalist overlords. In other words, as also, indeed, in Russia in 1917 and China in 1949, the ‘communists’ ostensibly took power in countries that Marx and Engels would have considered economically and socially distant from the ripe and predestined moment of violent revolutionary transition. Nevertheless, the communist road map was the only one handed to the North Koreans by the Soviets. But soon enough, as in Russia and China, ‘communism’ had morphed into a Korean-style totalitarianism of the ‘left’, as opposed to the totalitarianism characteristic of the ‘right’, aka fascism. That, at least, was how the story was told.

We still basically see politics today in terms of the binary ‘left’ and ‘right’, which is why Hitchens could imagine only a choice between seeing North Korea as on the extreme political ‘left’ ‘(communism) or extreme political ‘right’ (fascism) As racism and xenophobia were part of the fascist package, they placed North Korea on the ‘right.’ But this shoehorning into familiar political polarities risks losing sight of significant specific characteristics - but also characteristics of importance more generally beyond North Korea. For it is increasingly obvious that these polarities inherited from the European nineteenth century, never did fit the Korean situation, but also no longer suffice to describe the current political situation more generally - in both the global north and south.

*

Back in the late 1940s some disenchanted former communists wrote a book entitled ‘The God That failed’, edited by the Englishman Richard Crossman (a former communist turned Labour Party Member of Parliament). Subtitled ‘A Confession’, it included the testimonies of, amongst others, the Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler, the French novelist André Gide, and the English poet and critic Stephen Spender. The book was a classic of the early Cold War. I remember that my father, a state school English teacher and life-long socialist and Labour Party voter, owned a copy of the English edition, and I read it as a teenager in the mid-1970s, and it probably helped me steer a moderate ideological course during the awful Thatcher years.

Koestler joined the Communist Party in late 1931 and left in early 1938, and became a very vocal critic. He begins his contribution by writing: “A faith is not acquired by reasoning…..From the psychologist’s point of view, there is little difference between a revolutionary and a traditionalist faith. All true faith is uncompromising, radical, purist”.

Koestler’s analyses still seems spot on, because what we are witnessing today is an overwhelming tendency to adopt a position based not on reason but on ‘faith’, a position that is reassuringly ‘uncompromising, radical, purist”. We can see this trait on both the ostensible ‘left’ and ‘right’, and it suggest another polarity which offers a more accurate diagnosis of our current situation. The characteristics described by Koestler encompasses both extremes within our current ideological situation – ‘Woke’ radical race theory and nationalist populism - putting them not at opposite ends of a political binary of ‘left’ and ‘right’ but rather together within a binary comprised of ‘faith’ rather than ‘reason’ based politics. In this context, it’s not so much a problem of what one believes but whether such belief is ‘faith’ based intransigence – rooted in the desire to hold to the belief uncompromisingly, and so to adopt the most radical and pure possibility - or rooted in a reality that is recognized as inevitably ambiguous and uncertain.

Another work that made an impression on me as a teenager in the late 1970s – courtesy of my History teacher, Mr. Reid – was philosopher Karl Popper’s ‘The Open Society and Its Enemies’. This two-volume study was written during Popper’s exile from the Nazis in New Zealand during the War and published in 1945. Popper’s discussion of the Western history of ‘closed’ societies from Plato to Hegel and Marx was way too sophisticated for my young mind, but his basic argument was one that I did understand, and also one that still seems to resonate. Popper wrote:

This book raises issues that might not be apparent from the table of contents. It sketches some of the difficulties faced by our civilization — a civilization which might be perhaps described as aiming at humanness and reasonableness, at equality and freedom; a civilization which is still in its infancy, as it were, and which continues to grow in spite of the fact that it has been so often betrayed by so many of the intellectual leaders of mankind. It attempts to show that this civilization has not yet fully recovered from the shock of its birth — the transition from the tribal or "enclosed society," with its submission to magical forces, to the 'open society' which sets free the critical powers of man. It attempts to show that the shock of this transition is one of the factors that have made possible the rise of those reactionary movements which have tried, and still try, to overthrow civilization and to return to tribalism.

I recently read a fine book by the author and historian of ideas Johan Norberg called ‘Open. the Story of Human Progress’, which was published in 2020. Norberg credits Popper with defining a central class of values which he wishes to promote as a model for society today. He writes:

Openness created the modern world and propels it forwards, because the more open we are to ideas and innovations from where we don’t expect them, the more progress we will make. the philosopher Karl Popper called it the ‘open society’. It is the society that is open-ended, because it is not a organism, within one unifying idea, collective plan or utopian goal. The government’s role in an open society is to protect the search for better ideas, and people’s freedom to live by their individual plans and pursue their own goals, through a system of rules applied equally to all citizens. It is the government that abstains from ‘picking winners’ in culture, intellectual life, civil society and family life, as well as in business and technology. Instead, it gives everybody the right to experiment with new ideas and methods, and allows them to win if they fill a need, even if it threatens the incumbents. Therefore, the open society can never be finished. It is always a work in progress.

When read in the light of the regime now oppressing North Korea, what Popper and Norberg write provide useful insights. The regime is almost a caricature of the ‘closed’ society. But more broadly, they suggest that we should move on from the binary ‘left’ and ‘right’ and instead see the situation in terms of those who practice politics on the basis of ‘faith’ compared those doing it on the basis of ‘reason.’ Unfortunately, all too often a position based on dogmatic ‘faith’ is the more appealing option, as it means one doesn’t have to qualify one’s beliefs by taking into consideration conflicting attitudes, positions or information. In short, one can dispense with doubt. As Sam Harris puts it, ‘faith’ in this sense means ‘what credulity becomes when it finally achieves escape velocity from the constraints of terrestrial discourse - constraints like reasonableness, internal coherence, civility, and candor.’ Harris was aiming to expose religious faith, but what he says could equally apply to extreme secular ideological faiths, too. Isn’t North Korea a system that has definitely achieved ‘escape velocity from the constraints of terrestrial discourse’?

Ultimately, what we should be striving for is a way of thinking about society that incorporates doubt and that turns away from the temptations offered by any models - religious or secular - that try to banish doubt and install certainty. The terms ‘open’ and ‘closed’ seem to me to be useful titles of more realistic road maps than ‘left’ and ‘right.’

*