Martial Law in South Korea (Cancelled)!

It’s Christmas Day. A lovely white Christmas, here in South Korea. For one reason or another, I haven’t written any blog entries since the summer. But today, I feel compelled to comment on the recent drama here in the Republic of Korea. I refer to President Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law declaration on 3rd December, which turned out to be the shortest period of martial law in history, as it was cancelled the next day.

It’s Christmas Day. A lovely white Christmas here in South Korea. From up there, where I took this photo, you can just see what must be, bar a few utterly failed states in Africa, the worst country on Earth: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. They’ll be no Christmas Day over there. Just more misery.

For one reason or another, I haven’t written any blog entries since the summer. Mostly, this is because I’ve been busy working on two new book projects and making art in my wonderful new studio. I’ll write more about these soon.

But I feel compelled to comment on the recent drama here in the Republic of Korea. I refer to President Yoon Suk-yeol’s martial law declaration on 3rd December, which turned out to be the shortest period of martial law in history, as it was cancelled the next day. But it’s certainly been a wake-up call about how vulnerable democracy is, but also how robustly it can protect itself.

*

Martial law officially involves the armed forces stepping in when civilian authorities have stopped functioning, as in the case of war, insurrection, or natural disaster. In democracies it is usually used in times of war, or in relation to a specific threat or crisis within the nation, in which case it’s not imposed across unilaterally. But the ROK’s relationship with martial law is unique, in that the nation was founded in 1948 under martial law due to the communist threat both from the DPRK and from within the ROK itself. Then the Korean War began, lasting from 1950 to 1953. In May 1961 there was an army coup, which brought General Park Chung-hee to power and began another long period of martial law. When Park was assassinated in 1979, a brief moment of non-military rule began, but this was stamped out that same year by the military, and another eight year period of martial law began, including the brutal suppression of the Gwangju uprising in 1980. In 1988 the first democratically elected President of the ROK was Roh Tae-woon heralded a period in which, until the 3rd December, there has never been martial law. A lot has changed in the republic of Korea since the 1980s, but this seems to have been missed by President Yoon.

The most important difference is that the ROK is now a working democracy. Another is that it is a powerful world economy. And another is that despite the threats of the DPRK, including nuclear threats, the two Korea’s are now living in totally unequal worlds, a situation that’s been acknowledged by the DPRK leadership’s decision to stop pretending they want a re-unified Korean peninsula. They recently even blew up on their side the roads that traverse the DMZ., effectively announcing their status as a prison-nation. Kim has also sent a large quantity of munitions to Russia, and several thousand of his elite forces are currently being put in the meat grinder in Ukraine. The DPRK is therefore as unlikely now to invade the South as at any time.

*

Here are some choicer extracts from President Yoon’s statement announcing martial law.

He begins by accusing his rivals, the Democratic Party, of the very thing he is about to attempt:

This is a clear anti-state act of conspiring to incite rebellion by trampling on the constitutional order of the free Republic of Korea and disrupting legitimate state institutions established by the Constitution and the law.

The lives of the people are of no concern, and state affairs are in a paralyzed state solely due to impeachments, special prosecutors, and the opposition party leader's shield (against prosecution).

Now, it’s true that Yoon has been a lame duck President for some time because his party lost out big time in local elections, and the winning Democratic Party has been blocking more or less all Yoon’s attempts at legislative reform. His wife is being investigated for accepting expensive gifts (bribes), and his popularity has plummeted. Yoon must have felt very frustrated. But this is hardly grounds for martial law. Therefore, like the military rulers of the pre-democratic Republic, Yoon sought to justify his actions by evoking the imminent threat from the DPRK:

Dear fellow citizens, I am declaring a state of emergency martial law to protect the free Republic of Korea from the threats of the North Korean communist forces, to eradicate the shameless pro-North anti-state forces that plunder the freedom and happiness of our people and to safeguard the free constitutional order.

And here’s the best bit of all, from towards the end of Yoon’s short statement:

Due to the declaration of martial law, there may be some inconveniences for the good citizens who have believed in and followed the constitutional values of a free democracy, but we will strive to minimize such inconveniences.

‘Inconveniences’! ‘Strive to minimize such inconveniences’! Yoon’s low assessment of the South Korean people is summed up here. Did he really believe they would only experience martial law as an ‘inconvenience’, as if it was nothing more than roadworks slowing down their commute home? What was in Yoon’s deluded mind? He seems to have lost touch with reality, or perhaps its more accurate to say reality got funneled into a very narrow space full of his petty political problems. He lost any sense of the Big Picture.

In the end, I felt very proud of the South Korean people, and most particularly of the army, whose top brass showed themselves to be far more wedded to democracy than the President and his cronies. Huge numbers of South Koreans rallied to democracy and sent the scoundrel packing. Unfortunately, Yoon is still at large. But not for much longer. Several Presidents (5, including the President and former general who led the 1979 coup, Chun Doo-hwan) have been impeached and/or given prison sentences, including death sentences. But all - except Roh Moo-hyun (President from 2003 -2008) who committed suicide - received pardons. Yoon Suk-yeol will therefore in all likelihood soon be the sixth ROK President to go to prison, and maybe will even be given the death penalty if he is found guilty of treason. But history suggests he will also be pardoned.

*

I was also struck by the timing of Yoon’s declaration of martial law, which was almost exactly one month after Trump was elected President (5th November). I can imagine that Trump will try the martial law card in the US in the not too distant future if it seems necessary. In fact, federal and state governments in the USA have declared martial law over 60 times during its history – for example, after Pearl Harbor in 1942 and until the end of World War Two. The last time was limited to a single town in Maryland during in 1963 Civil Rights Movement crisis.

What Yoon’s action exposes is the influence of the trend towards populist and authoritarian leaders which is undermining democracy and emboldening half-baked wannabees like Yoon to accelerate the process. In the case of the ROK, he totally underestimated the sound commitment of his country to democratic government of the kind that has checks and balances put in place to make sure no one person can try to do what Yoon did. He also underestimated the sea change in the minds of South Korea’s military leaders, who refused to be employed as his bully boys.

But I’m wondering if the Constitution of the United States, which is famously buttressed by such checks and balances, is going to be able to take the strain of another Trump Presidency. The US seems so utterly ravaged. To borrow Ezra Pound’s words, it’s almost beginning to look like the US is a ‘botched civilization’.

*

Here’s a glimpse of one of my new ‘LP Paintings’, in which I make monochrome paintings based on the covers of LP’s, preserving only the original typography of the title and artist. In this case, its an LP by Bob Dylan. The title seems timely. I liked the way the sunlight in my studio played over its surface, so I turned it into a New Year’ card.

Murderous keys to history

We who live near to the DMZ like to joke that people in Seoul are more endangered by North Korea than we are, that we’ll watch the missiles flying high over our heads, aiming at targets in the densely populated metropolis. And anyway, as you can see from the photograph at the start of today’s blog, there’s a handy bomb shelter just one hundred meters from our house.

But this shelter probably wouldn’t be much protection against marauding North Korean soldiers if, for some extraordinary reason, all the many South Korean soldiers garrisoned around here took their time arriving to project us. In such propitious circumstances, would the North Koreans wreak in our village such ghastly vengeance on me, my wife, and all my neighbours – the children, pregnant women, elderly, and their pets - as Hamas did in Israel? This is more than just a macabre thought-experiment, because it helps foreground what is specific about the worldview of Hamas.

The bomb shelter in our village near the DMZ.

Recently (November 14), BBC News on-line ran an article headlined ‘South Korea fears Hamas-style attack from the North’. It began: ‘On Sunday, when South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol hosted US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin at his home for dinner, he urged Mr Austin to be vigilant against any type of North Korean attack, including surprise assaults "resembling Hamas-style tactics".’

We who live near to the DMZ like to joke that people living and working in Seoul are more endangered by North Korea than we are, that we’ll watch the missiles flying high over our heads, aiming at targets in the densely populated metropolis. And anyway, as you can see from the photograph at the start of today’s blog, there’s a handy bomb shelter just one hundred meters from our house. But this shelter probably wouldn’t be much protection against marauding North Korean soldiers if, for some extraordinary reason, all the many South Korean soldiers garrisoned around here took their time arriving to project us. But in such darkly ‘propitious’ circumstances, would the North Koreans set about wreaking in our village such ghastly vengeance on me, my wife, and all my neighbours – the children, pregnant women, elderly, their pets - as Hamas did in Israel? This is more than just a macabre thought-experiment, because it helps foreground what is specific about the worldview of Hamas. These North Korean soldiers will certainly have been conditioned to hate South Koreans (and a British citizen whose nation supported the Republic of Korea during the Korean War and has done so ever since), but will they act with such extreme and calculated savagery as the Hamas militants did in Israel? Will they record their deeds on social media? Does the ‘alternative’ reality which the North Korean soldiers inhabit also put them beyond the rules of war respected by open societies and inscribed in UN charters?

*

Hamas and the North Korean Communist Party are vastly different political organizations, but both are variants of totalizing forms of ideology. Increasingly, however, in Israel/Palestine two rival and implacably hostile totalizing religious ideologies confront each other: Islamic fundamentalism and Zionist settler fundamentalism. These ideologies offer to believers a reality tailored to achieve the illusion of absolute control of time - the past, present, and future – and of space - both physical or profane and sacred. As Hannah Arendt observed in the late 1940s in relation to what she called ‘totalitarianism’, this kind of ideology “differs from a simple opinion in that it claims to possess either the key to history, or the solution for all the ‘riddles of the universe,’ or the intimate knowledge of the hidden universal laws, which are supposed to rule nature and man."

Absolute faith in possessing the ‘key to history’ is what unites the Islamic fundamentalist Hamas and the Zionist settlers with the so-called ‘communist’ system of North Korea. They all share the belief that they have been empowered to see the inescapable future. They believe they possess the secrets of prophecy. Totalism breeds and sustains a mindset founded on the wilful absence of alternatives, on the compulsory, the single-minded, and on autosuggestion, in that the prophesy is apparently self-fulfilling.

Let’s stop for a moment to consider how we - by which I mean those of us lucky to be able to say in public that we are liberal free-thinkers - differ from these fanatics. What do we take for granted when we reflect on the relationship between the past, present, and future?

Unlike members of Hamas, Zionist settlers, or card-carrying members of the North Korean Communist Party, we assume that life is ambiguous and multi-layered. We accept that any potential actions we take respond to meanings that exist on several historical dimensions. More or less articulately, we think about the short- middle- and long-term. The short-term involves the succession of the before and after that constrain our everyday actions, which means any prognosis we might make about the world is bound situationally. The middle-term turns our attention to trends deriving from the course of events into which enter many factors beyond our control or that of our group or ‘tribe’ as acting subjects. This means we take into account transpersonal conditions. On the long-term plane we factor in ‘metahistorical’ duration, that is, certain anthropological constants that resist or elude the historical pressures of change, and so do not respond to immediate political pressures in the present.

The believer caught in the iron grip of a totalizing system does not see the world like this at all. Emboldened by faith in the capacity to prophetically foretell the future, they willingly accept the absence of alternatives and work to conform events to their prior belief-system. This means they reject any view of their situation based on an understanding of short-term succession that constrains everyday actions. They do not see themselves as bound situationally. They also reject middle-term trends. The only transpersonal conditions they believe in are those that conform to the shape of the prophecy. This prophecy also determines the structure of the long-term plane of anthropological constants; in a religious ideology, human destiny is uniquely tied to the demands of a deity, or in non-religious ideologies, in deity-like humans, such as the Kim dynasty in the DPRK who rule by a kind of supra-human ‘divine right’.

But, of course, there is a fundamental difference between the ideology of Hamas and Zionism on the one side, and the DPRK on the other: the influence of monotheistic religion. But while the religiously centered worldviews of Hamas and Zionism share these common roots in religious tradition, Hamas is far more radical. Like other Islamic fundamentalist movements, such as ISIS, Hamas believes in violent jihad – Holy War. Followers consider that the teachings of Islam contained in the sacred texts legitimize, indeed glorify, attacks on non-believers, and that the only just future goal is the global establishment of the Islamic caliphate. As such, all means justify the achievement of this single future. In fact, there is no limit to the actions permissible in the present in order to reach this desired end, which also entails the greatest of rewards for those who take up jihad: a believer who dies during jihad is cast as a martyr who goes directly to paradise – Jannah. The ‘infidels’ they slay, meanwhile, have been rewarded with what God wants for them: eternal damnation in Hell - Jahannam.

*

As many commentators on the left indicate, the state of Israel is in danger of becoming what they call an ‘apartheid’ nation governed by Zionist totalizing ideology. But for the time being, at least, it remains a democracy within which, during the vengeful assault on Gaza, attempts are credibly (and often futilely) made to act according to the rules of war. In his ‘Making Sense’ podcast Sam Harris proposes we try a sobering thought-experiment. We know that Islamic fundamentalists are willing to use their own people – other Muslims – as human shields. In some senses, this is precisely what Hamas is doing now in Gaza. What if Israel tried the same tactic? What if their soldiers rested their gun barrels on the shoulders of Israeli children or set up a command post under a hospital? What would Hamas fighters do? The answer is as obvious as it is terrifying: all the Israelis would be massacred. However dreadfully compromised Israel’s position is today, it’s leadership – even the extremist Zionists - still find using human shields to be beyond the ethical pale. Hamas and other Islamic fundamentalist movements do not.

Back in the late 1940s, Hannah Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism was limited to political ideologies. In that period, religion really did seem to have lost its influence over politics. But since the end of the Cold War it has become obvious that religion definitely remains a significant and divisive force. This is a fact that commentators on the left seem reluctant to acknowledge. But now we are being forced to recognize the limits of the secular mindset in understanding glabal conflicts. Treating the struggle in Israel/Palestine as primarily about ‘decolonization’, about an ‘apartheid’ behemoth crushing a defenseless and displaced people, is to apply an optic that is dangerously narrowly secular and Western. For example, the slur ‘apartheid’, derives from the racist and secular system imposed for a period by whites on blacks in South Africa. Historically, that system did not entail religiously motivated racism or establish itself on a global and radically exclusionary vision of society. Its a critical template that seems viable to a secular culture, but it fails to recognize the significance of the religious dimension to the conflict.

As Sam Harris emphasizes, it is almost impossible for secular Westerners to grasp just how different this worldview of the jihadist or Islamic fundamentalist is, and how totally the true believer embraces its core tenets. Harris notes that especially we liberals on the left often bend over backwards to try to rationally analyze these people’s beliefs and actions according to the narrow humanist criteria bequeathed to us by Western humanist sociology and anthropology. What we fail to understand is how totally their worldview is at odds with and premised on the total rejection of our own worldview.

This is why calling the brutal assault by Israel on Gaza ‘genocide’ fails to describe that is taking place. ‘Genocide’ is defined as the deliberate killing of large numbers of people of an ethic or national group. Israel isn’t deliberately killing Palestinian civilians in Gaza. But there is no doubt that its thirst for revenge has made it insensitive to the costs its revenge entails, and blind to the seemingly obvious fact that violence will always be met by more violence.

The situation in Israel/Palestine is so tragically complex that making any kind of valid prognosis on the basis of the short-term is almost impossible – for example, a political solution is essential but, right now, it looks impossible. The mass protests against Israel taking place worldwide - including in Seoul - are mired in seeing the crisis only in the short-term view. But things look bleak on the mid-term level; so many interpersonal and impersonal agents are involved – not just the Israelis and Palestinians and their intertwined histories. And if we attempt to rise above the bloody fray and take in the long-term view, what do we see? Unfortunately, nothing very encouraging. Just the tragic truth that eventually implacable rivals who are trapped in the spiral of revenge lose the will to fight and learn to co-exist in peace.

*

Which brings me back to the chances of us, here near the DMZ, being gruesomely tortured before being killed, Hamas-style, by marauding North Korean soldiers. One thing for certain, the North Korean invaders wouldn’t be sharing their vile actions on WhatsApp and Facebook using our phones, for the simple reason that they won’t know how to use the technology, and anyway, no one back home could answer their calls. But to end on a less facetious note; the ideology within which the North Korean soldiers live and breathe may be repellent to the values of the open society, but it does not glorify sadistic violence against religious non-believers and those of us who have rejected religion entirely. Jihadist violent antipathy to the world makes the so-called Juche ideology of the DPRK seem relatively – I stress ‘relatively’ - anodyne. It is familiar, and not so hard to encompass within our own Western worldview. Jihadism, by contrast, is wholly other. But more than that: it is a self-consciously adopted position premised on the destruction of its own other, which is not just we liberals but anyone who doesn’t share their extreme interpretation of Islam. Co-existence is therefore not an option. This is why a ceasefire isn’t a viable option.

North Korean soldiers do not believe that when they commit atrocities and then die fighting that they will be rewarded for their crimes by going straight to Paradise. That any children they murder, because they are innocent in Allah’s eyes have been fast-tracked to paradise, and that I and everyone else they get their murderous hands on, will roast for ever in Hell. This, I suppose, is some kind of cold comfort.

NOTES

The BBC article can be read at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-67411657

The Hannah Arendt quotation is from The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951).

Sam Harris’ excellent Making Sense podcast on this subject can be heard at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oFBm8nQ2aBo

I draw for my discussion of short- mid- and long-term thinking about time and history on Reinhart Koselleck’s The Practice of Conceptual History. Timing History, Spacing Concepts, translated by Todd Samuel Presner and Others (Stanford University Press, 2002) Chapter 8.

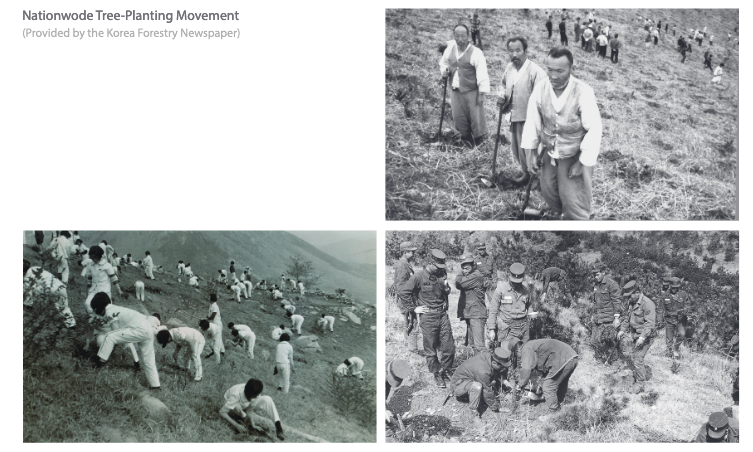

The South Korean tree-planting ‘miracle’

One of the most inspiring, and also least known, reforestation programmes took place here in the Republic of Korea.

As a result of the recognition of the role of trees in controlling climate change, at the recent COP27 more than 25 countries agreed to hold each other accountable for a pledge to end deforestation by 2030. The talk was not just about ‘net-zero’ but about ‘nature-positive’.But arresting deforestation must also be matched by ambitious global programmes of reforestation. One of the most inspiring, and also least known, took place here in the Republic of Korea. As in many other places, the degradation of forests on the Korean peninsula was already a problem as long ago as the eighteenth century, but it had reached crisis proportions by the period of Japanese colonization (1910 – 1945). The Korean War (1950 – 1953) destroyed almost half of the remaining forested land, and by the 1960s deforestation had become a serious problem, not just in relation a lack of lumber and firewood but because the erosion control provided by trees had also been destroyed, and heavy rainfalls during the summer monsoon season regularly caused major damage.Regions of South Korea before the reforestation campaign.

From 1962-1987 the Republic of Korea’s National Reforestation Programme was responsible for remedying this dire situation through organizing the systematic planting of huge numbers of seedlings sourced from government-owned nurseries, forest co-ops, and locally grown in villages. My wife, Eungbok, tells me that every year in springtime during her high school years she would head for the hills with her classmates on designated tree planting duties. The results are plain to see by looking at photographs of the same landscape as it was prior to the Programme and then today. South Korea is a reforestation success story. Before and after.

This means, however, there are almost no old-growth forests in Korea. All the species of tree around where we live are no more than about forty of fifty years old. Also, the reforestation campaign made some mistakes: it relied too heavily on planting rapidly growing coniferous trees, and reliance on a limited number of tree species made the new forests susceptible to pests and disease, something that subsequent global reforestation programmes have learned from. And unfortunately, despite this amazing feat of forestation South Korea remains a major importer of timber, including from countries most heavily implicated in illegal logging.NOTESFor today’s post I referred to Lessons learned from the Republic of Korea’s National Reforestation Programme, published by the Korea Forest Service. https://www.cbd.int/ecorestoration/doc/Korean-Study_Final-Version-20150106.pdf. The images accompanying this post are from this source.

Authority v Liberty. The curious case of South Korea

What kind of cosset do you want?

In my last post, I mentioned the censorship I have experienced in relation to the Chinese translation of my book, Seven Keys to Modern Art. Last week, in my class here in Korea with mainland Chinese students I brought it up with as much subtlety as possible. In the class, I discussed sociological approaches to modern art. As I am using Seven Keys as a textbook, and between them the ten Chinese and one Korean students have the Korean, English, and Chinese versions, they could compare editions. I pointed out the gap in the Chinese version between Barbara Kruger and Bill Viola, which is where Xu Bing should be. He’s gone because in my discussion in the book I refer to his shocked response to the repression in Tiananmen Square, which is still very much taboo in mainland China.

The students seemed very surprised. But also understandably rather tight-lipped about the omission.

I taught them the word ‘censorship’.

*

In the same class I showed the diagram above. It’s a rather good way of tracking the difference between China and the West, but also the unique position of the Republic of Korea. The West lies at the bottom right: ‘Individual Liberty’. China is up at the top right: ‘Collective Authority’. Hence the censorship. South Korea is somewhere in between. It’s an experiment in ‘Collective Authority plus Individual Liberty’.

The way in which these societies dealt with Covid helps to illustrate the differences. With its ‘zero tolerance’ attitude, China applied from the start its ‘Collective Authority’ model to the crisis. The West, by contrast, adopted an ‘Individual Liberty’ approach. South Korea dealt with Covid by mixing the two.

At first, ‘Collective Authority’ seemed the best option for everyone. The East Asian countries, being more attuned to this model, were quick to respond by introducing the necessary measures. China went to lockdown. The Western nations panicked, because ‘Individual Liberty’ is so obviously inappropriate in such a crisis, and they too went for lockdowns as an extreme recourse. South Korea managed to avoid lockdown, by contrast, but also any extreme spread of the virus. This is because with its unusual blend of ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ it was able to steer a middle course, epitomised by the skilful tracking of cases and the strict implementation of individual quarantines.

But with the evolution of the virus into the Omicron variant, ‘Individual Liberty’ has proven, rather surprisingly, in the long run a more robust social structure for dealing with the pandemic. China is now castrating itself by still pursuing the impossible goal of zero covid, even imposing lockdown once again in Wuhan, where the whole thing started. Only a society founded on ‘Collective Authority’ could work this way, that is, could be so rigid and maladaptive. Meanwhile, South Korea has segued to a situation in which the pandemic is confidently under control but in which people are still wearing facemask, because of the ‘Collective Authority’ component of this society. But it seems to me that the West has careened too fast away from the disagreeable experience of imposed ‘Collective Authority’ back towards a dangerous level of maskless ‘Individual Liberty’.

In this context, the tragic events in Itaewon, Seoul, over this Halloween weekend can be interpreted as an unfortunate unintended consequence of South Korea unique social blend, or social experiment. Inevitably, ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ exist in uneasy tension. South Koreans tolerate a – to Westerners - very high level of group control, but they are also primed by Western ideals of ‘Individual Liberty’. The result in this particular case was a massive feeling of release amongst the young after the restrictions imposed during the pandemic. But, ironically, their desire for individual liberty expressed itself in a very collective fashion!

Image source: http://factmyth.com/understanding-collectivism-and-individualism/

Getting Acquainted with Nothing

Detail of the flag of the Republic of Korea, featuring the yin-yang symbol.

Nothing can sneak up on us when we least expect it, an uncomfortable fact that has certainly been amplified during the Covid-19 crisis as millions of people have been obliged to self-isolate. In fact, negative feelings of failure, envy and resentment, and experiences of loss, absence, sickness and death seem to shape our lives more than positive feelings and experiences. Despite our desire to hold onto ‘positive’ emotions and thoughts, we often find ourselves trapped in the company of the ‘negative.’

There is a battle raging inside all of us between the internal and external forces moving us forward and helping us grow, and those holding us back and defeating us. Intrinsic to our emotional and intellectual life are conscious or unconscious, willed or unwilled, encounters with ‘nothing’ – with pessimistic, critical, skeptical, apathetic, cynical, violent and destructive attitudes. It can be encountered as a very personal matter which poses deep existential problems, as when we conclude that we live in a meaningless abyss between the nothingness before birth and the nothingness after death.

Such negativity can form the basis for judgments about the meaning of existence as a whole, as when Macbeth says that life is “ full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.” This overwhelmingly negative feeling can become so permanent that only suicide seems to offer a way out. ‘There is this emptiness in me. All the things in the world are not enough to drown out the voice of this emptiness that says: you are nothing’[1], writes the contemporary Chinese-American novelist Yiyun Li, giving new voice to the perennial sense of despair. Acute awareness of existential worthlessness can have specific causes - cruel parenting or the trauma of war - but it can also, as Blaise Pascal observes, simply be the result of someone being “in complete repose, without passions, without occupation, without amusement, without duty’. For at such moments, “Immediately there arises from the bottom of his soul boredom, grief, chagrin, scorn, despair.”[2]

And yet such feelings of existential nothingness can also lead to the recognition that our feeling of groundlessness is an inevitable consequence of being over-dependent on some basic habits of thinking. Buddhist teachings state that all things are without essential and enduring identity, that all existence is interconnected in a chain of co-dependent becoming within a state of constant flux. Therefore, a meditation on one’s own emptiness or nothingness can aid in relinquishing our grasp on the binary oppositions that usually dominate existence, and so be the prelude to an enlightening experience of peaceful mindfulness.

In this sense, exploring how Nothing performs, animates, and transforms can be a potential prelude to a healing process in which the usual segregations in our thinking begin to seem less rigid and therefore less terrorizing. Once we have familiarized ourselves with the negative, we can start to think dialectically: not negative v positive, but rather negative-positive, where we are positioning ourselves in a ‘fuzzy,’ in-between position, one from where we can pivot back and forth between poles.

The Taoist concept of yinyang is an ancient system of dialectical thinking. Buddhism calls itself the ‘middle way,’ because it invites the merging of contradictions, or the mutual conversion of binary opposites. These traditions aim to help us to stay in touch with the undelimited whole. As the Zen monk Hui Neng declares: “ All things are in your essential nature. If you see everyone’s bad and good but do not grasp or reject any of it, and do not become affected by it, your mind is like space – this is called greatness”. [3] The ‘nothing,’ ‘void,’ or ‘emptiness’ of Buddhism isn’t therefore referring to the absence of ‘something,’ and is intended to signal an unconceptualizable connectedness which cannot be grasped, circumscribed or delimited.

[1] Yiyun Li, Dear Friend, from My Life I Write You in Your Life, Random House, 2017

[2] Pascal, Pensées, No. 201

[3] Hui Neng, ‘The Sutra of Hui-Neng, Grand Master of Zen, With Hui-neng’s Commentary on the Diamond Sutra, trans. Thomas Cleary, Boston and London: Shambhala, 1998, 17