‘Flood the Zone with Shit and Howling’. Lessons from North Korea

Sometimes, I’m grateful to North Korea for helping me to see more clearly what’s happening in the world more generally. In this case, their ‘noise-bombing’ and balloon sending has helped me understand President Trump.

A balloon from North Korea carrying garbage and excrement lying in a South Korean rice field in the Spring of 2024.

These days, a deliberately unsettling medley of sounds are being blasted across the DMZ by North Korea. It’s what’s known as ‘noise bombing’, a nasty aural dimension of psychological warfare. The sounds mostly consist of deep apocalyptic droning, wailing sirens, and on occasion, screaming women and howling wolves. We can sometimes hear some of the sounds in our village - it depends how strong the wind is blowing from the north - but so far, I’ve only been able to detect the droning and sirens. South Korea sends its own ‘noise bombs’ towards the North - K-Pop music and other good news about living in a free country. Before, when the North noise-bombed the South they also used patriotic music and loud-speaker announcements about how their country is a workers’ paradise.

This new unsettling development signals a change in strategy in which the North no longer uses ‘noise-bombing’ as propaganda in the obvious sense. The change parallels another new strategy: sending helium balloons across the border which now are not filled with DPRK propaganda, as before, but with garbage and human and animal excrement. So far, none have come down near our village, so I have only seen them in the news media. This is ostensibly a response to actions originating in the South - balloons sent by North Korean defector groups and Christian organizations which contain propaganda. In fact, it’s an illegal activity in the South, but nevertheless continues to be a regular occurrence..

Both the howling and the shit are a reflection of Kim Jong-un’s declaration that North Korea’s goal is no longer a re-united Korea, and that the South is now an implacable enemy to be ultimately destroyed. This has, of course, been the truth since the Korean War, but until last year the North persisted in maintaining the fiction of reunification as an inclusive aspect of their much bigger fiction – that of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as a whole. This fiction included the assumption that the people in the Republic of Korea were oppressed and just waiting to be liberated by the North. Now the North has re-written or erased part of the official narrative, evidently because it no longer serves any practical purpose, and can be discarded without threatening the status quo in the North. as I noted in my previous post, there are obvious reasons for the change in relationship. Almost no one in the North is old enough to remember when there was just one Korea, and who perhaps have relatives living in the South. The new leadership under Kim Jong-un is much too young to know anything except two Koreas, and have no sentimental attachment to the South. But I also think something more momentous is going on.

*

Communication theorists refer to what they term ‘information noise’: an external input into a communication channel between a sender and a receiver that potentially obscures or makes incomprehensible the signal,or the message. In other words, an increase in ‘noise’ results in a decrease in determinable meaning. There are various categories of such ‘noise’. The North Korean variety in the ‘noise bombing’ is ‘physical noise’, that is, a disturbance or interference coming from an external source that obscures or obstructs the signal. In the case of the balloons, it’s ‘semantic noise’, an interference in the common background or knowledge that makes sharing ideas possible..

But North Korea has weaponized this ‘physical’ and ‘semantic noise’, and by so doing turned it into a kind of information. Paradoxically, the very targeted noisiness of the ‘noise’ becomes a message. It signals that North Korea now assumes there is the total absence of a shared, common cultural background or store of knowledge, and so it is impossible and pointless to freight ‘noise bombing’ with any information in the form of communicable ideas.

The North consciously intends through their latest aggression to show what they think of the South’s propaganda efforts, and to announce the fact that North Korea has given up trying to communicate a message that the receivers, South Koreans, can understand.. However, I think one can argue that unconsciously the North is finally telling us the truth about their own regime. The shit and howling says quite a lot about the sender, because they an inverted expression of what life is really like in North Korea, a nation where communication is effectively entirely devoid of ‘noise’. Everything is organized so that on all levels – physical, physiological, psychological, semantic, cultural, technical, and organizational – the regime can optimally deliver a pure message without ‘noise.’ This is another way of saying that North Korea is a totalitarian state. In a democratic society there is always bound to be ‘noise’ in any communication, especially in a multi-cultural society with multiple senders of messages - a Babel magnified infinitely by the Internet.

*

Sometimes, I’m grateful to North Korea for helping me to see more clearly what’s happening in the world more generally. In this case, their ‘noise-bombing’ and balloon sending has helped me understand President Trump. During his first presidency, Steve Bannon famously coined the motto ‘flood the zone with shit.’ Well, North Korea have inadvertently taken his advice. They are trying to flood the Demilitarized Zone with ‘shit’ – quite literally in some instances. For Bannon was advocating a strategy of maximum communication ‘noise’. You create so much of it that the real messages are rarely received.

So, what is the real message? It looks more and more likely that the real message refer to a coming coup d’etat. The ‘noise’ makes it possible for the coup to happen in slow-motion, so to speak. Without the usual violence, the messiness of storming the Capitol. When will freedom-loving Americans wake up to this increasingly obvious fact? I certainly hope they don’t copy the Germans after they elected Hitler in 1933.

NOTES

The image is a screenshot from:

https://www.euronews.com/2024/10/24/north-korean-balloon-dumps-rubbish-on-south-korean-presidential-compound-a-second-time

For more on ‘information theory’ see: https://www.soundproofcow.com/4-types-of-noise-in-communication/?srsltid=AfmBOorXhkA_oW2-HHLfmkLeVIe-iBH5uXlu6qjjjqfJxbkmyDQDZgEF

https://www.mosaicprojects.com.au/WhitePapers/WP1066_Communcation_Theory.pdf

Is Kim Jong Un Preparing for War?

I borrow today’s post title from a scary recent article (January 11th) by North Korea experts Robert L. Carlin and Siegfried S. Hecker on the respected website 38 North. In the first paragraph the authors write:: ‘The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950. That may sound overly dramatic, but we believe that, like his grandfather in 1950, Kim Jong Un has made a strategic decision to go to war. We do not know when or how Kim plans to pull the trigger, but the danger is already far beyond the routine warnings in Washington, Seoul and Tokyo about Pyongyang’s “provocations.” In other words, we do not see the war preparation themes in North Korean media appearing since the beginning of last year as typical bluster from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.’

‘Who wants an Americano?’ Ordering coffee, DPRK-style.

Today’s blog title is borrowed from a scary recent article (January 11th) by North Korea experts Robert L. Carlin and Siegfried S. Hecker on the respected website 38 North. In the first paragraph the authors write:

The situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time since early June 1950. That may sound overly dramatic, but we believe that, like his grandfather in 1950, Kim Jong Un has made a strategic decision to go to war. We do not know when or how Kim plans to pull the trigger, but the danger is already far beyond the routine warnings in Washington, Seoul and Tokyo about Pyongyang’s “provocations.” In other words, we do not see the war preparation themes in North Korean media appearing since the beginning of last year as typical bluster from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

A key reason for the heightened concern was the 9th Enlarged Plenum of 8th WPK Central Committee, which met in late 2023 (shown in the photograph above). The Rodong Sinmun, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Workers' Party, reporting on the Plenum, announced the following:

For a long period spanning not just ten years but more than half a century, the idea, line and policies for national reunification laid down by our Party and the DPRK government have always roused absolute support and approval of the whole nation and sympathy of the world as they are most just, reasonable and fair. But none of them has brought about a proper fruition and the north-south relations have repeated the vicious cycle of contact and suspension, dialogue and confrontation.

If there is a common point among the "policies toward the north" and "unification policies" pursued by the successive south Korean rulers, it is the "collapse of the DPRK’s regime" and "unification by absorption". And it is clearly proved by the fact that the keynote of "unification under liberal democracy" has been invariably carried forward although the puppet regime has changed more than ten times so far.

The puppet forces’ sinister ambition to destroy our social system and regime has remained unchanged even a bit whether they advocated "democracy" or disguised themselves as "conservatism", the General Secretary [Kim Jong Un] said, and went on:

The general conclusion drawn by our Party, looking back upon the long-standing north-south relations is that reunification can never be achieved with the ROK authorities that defined the "unification by absorption" and "unification under liberal democracy" as their state policy, which is in sharp contradiction with our line of national reunification based on one nation and one state with two systems.

The DPRK claims that as the goal of unification has been made impossible by the United States, and the South is merely its ‘puppet’, there is no point in pursuing it any longer. Since the Plenum, it has therefore formally abandoned unification for the first time. This is the worrying bit for Carlin and Hecker. It does seem to signal a new and dangerous low, especially when seen in the light of recent rapprochement between the two Koreas (and the United States). During the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Inter-Korean relations had been gradually improving, despite occasional hickups. In 2000 there was an Inter-Korean Summmit during which the ‘June 15 South-North Joint Declaration’ was adopted. In 2007 another Inter-Korean Summit adopted the ‘Declaration on the Advancement of South-North Relations, Peace and Prosperity’. One tangible sign of this was the construction of the Gaeseong Industrial Complex, which we can see from a local (fortified) hill on a clear day. There, in a bizarre expansion of capitalist entrepreneurial spirit, South Korean companies were permitted to build factories and warehouse and employ cheap North Korean workers. In 2018 two summits in close succession took place, during which Kim Jong Un crossed the border into South Korea and the President of South Korea, Moon Jae-in, successfully brokered the signing of the ‘Panmunjeon Declaration’. This led to an agreement to facilitate further advancements in inter-Korean relations and to establish permanent peace on the peninisula, which included a pledge by the North to aim towards denuclearization via the dismantling of a nuclear test site. There was also the first North Korea-US summit in Singapore with President Trump, who also visited Panmunjeon.

In retrospect, this whole chain of seemingly auspicious events seems to have been little more than an extended publicity campaign on both sides, or more charitably, a case of wishful thinking on the side of the South and the United States. For it seems clear that the North never intended to fulfill its ostensible pledges, or would only do so if the South and the United States went much further than they reasonably could towards ‘normalizing’ relations. For example, ‘denuclearization’ meant very different things for each side.

Over the past five years, North Korea has scrapped the entire agreement. A sign of the souring of relations was the fact that Gaeseong was closed temporarily by South Korea in early 2016 as a response to North Korean missile tests and then immediately permamently shuttered by the North. It’s now a ghost town. North Korean nuclear tests and its development of long-range missiles has grown apace. North Korea is now ignoring telephone calls from South Korea across the multiple Inter-Korean hotlines, which have been a key channel through which to defuse tension.. Key political changes outside the DPRK have also prompted its sea-change; in the South there is now a much more hawkish President who no longer sees any point in being accommodating to Kim Jong Un like his predecessor, and in the United States, Biden has reversed the (ludicrous) ‘buddy’ diplomacy initiated by Trump..

But it seems, fortunately, that not many other NK watchers agree with Carlin and Hecker’s dire, quasi-apocalyptic, warning. As an article posted on BBC online (23rd January) informs us, other experts note that the country is apparently due to reopen to foreign tourists this month, and has also sold so many shells to Russia it is probably not in a strong position to launch a serious attack. Economically, the DPRK’s is a basket case; in 2022 its economy shrank for a third consecutive year, and the nation is classed as one of the poorest countries on earth (the ROK is the 10th largest global economy). Despite the display of fancy weapons during the numerous military parades, and the firing of of expensive missiles into the sea, the numerically huge North Korean army is poorly equipped and would be no match for the South Koreans and their American allies.

The bombastic rhetoric evident in North Korean media is primarily aimed at the domestic audience, and so obviously shouldn’t be taken at face value. If you read Rodong Sinmum’s report on the Plenum one immediately gets the general idea. Here’s an extract from near the beginning of the very long article:

Thanks to the outstanding leadership of our Party and the indomitable efforts of our people intensely loyal to it, precious ideological and spiritual asset was provided to dynamically promote the development of the state in the new era, a scientific guarantee was established to definitely set the goal and direction of the new year’s struggle and accurately attain them and the mightiness and invincibility of our great state were strikingly proved by entities of the rich country with strong army.

In a nutshell, we achieved epochal successes in providing favorable conditions and a solid springboard for further accelerating the future advance in all aspects of socialist construction and the strengthening of the national power through this year’s struggle, not merely passing the third year of the implementation of the five-year plan that we had planned.

Years after the Eighth Party Congress were recorded with unprecedented miracles and changes, but there had been no year full of eye-opening victories and events like this year.

‘Epochal success’! It’s all total bullshit, of course. The disjunct between what is publicly pronounced by the only newspaper of the DPRK’s Workers’ Party and the grim reality is truly mind-bending, or gut wrenching.

*

Since the end of the Korean War, the term ‘unification’ has always been ambiguous. “Unified’ under which of the diametrically opposite systems? The Korean War began when the North invaded the South with the goal of unifying Korea by force. This has always remained its intention, despite claims to the contrary. Kim Jong Un says as much by protection his regime’s intentions onto the Republic of Korea by claiming its goal is “unification under liberal democracy.” But, actually, he’s right. How else could real unification happen except through political as well as economic union?

No one I’ve talked to in the South over the years – people of all ages – believe unification is a real option. It has long been a fiction neither side really believes in. It’s said that if the North’s regime collapsed and the South took over, like West Germany which absorbed communist East Germany after the end of the Cold War, it would swiftly bankrupt the South. The economic disparity between the two Koreas is far, far greater than between the two Germanys. But so too are the social disparities; South Korea has the fastest broadband connection in the world while North Korea doesn’t even have the Internet (for reasons of social control).

One prosaic reason for the North Korean announcement having less visceral impact than it would once have had is the fact that very few Koreans on either side of the DMZ remember a time when the Korean peninsula actually was united., and if they do, it was because it was a Japanese colony not an independent nation. Many of the graves around where we live are for Koreans born in the North who wanted to buried within sight of their homeland. My wife’s father escaped from Pyeongyang as a young man, fought in the Korean War, married a South Korea and never learned what happened to the family he left behind. Before his death, he tried and failed to find relatives during the family reunions organized since 1985 – the last one was in 2018. These reunions wer part-and-parcel of the thawing of animosity between the two Koreas. For his generation, the loss of ‘unity’ was felt as a very personal level. But Kim Jong Un was born in 1984, and so he has no direct experience of a time when there was one united Korea, nor do most North and South Koreans today.

*

In the United States it is also seems that, most obviously for MAGA supporters and QAnon conspiracy theorists, facts are of little importance in framing public and private discourse,. But at least there are alternative narratives within the reach of every citizen. But in North Korea there is just the one narrative. All any North Korean citizen knows is the fairy story the Party tells. Which is why the punishments for accessing alternative narratives, via South Korean tv show and music, for example, is punished severely, and there is no Internet. Human Rights Watch’s report for 2023 writes:

The North Korean government does not permit freedom of thought, opinion, expression, or information. All media is strictly controlled. Accessing phones, computers, televisions, radios, or media content that is not sanctioned by the government is illegal and considered “anti-socialist behavior” to be severely punished. The government regularly cracks down on those viewing or accessing unsanctioned media. It also jams Chinese mobile phone services at the border, and targets for arrest those communicating with people outside of the country or connecting outsiders to people inside the country.

But the disturbing fact is that even in a country that enshrines freedom of speech in its constitution, people often seem more content when there is only one story to choose from. Anxiety and insecurity (and therefore the potential for change and self-transformation) come when doubt sets in and one questions what one hears and sees. Such doubts are a direct result of encountering alternatives and having to make choices. But the unprecedented access to information made possible thanks to the Internet has not led people to become more open to and comfortable with different narratives. Instead, it often makes them even more insecure. They are overwhelmed by a tsunami of varied and often contradictory narratives, and in defense are inclined to withdraw into ‘siloed’ information zones.. They wrap themselves beneath a comfort blanket comprised only of what conforms to the narrative which makes them feel secure..

Amazingly, it seems a fairy story can trump lived reality. Or, lived reality is all too often experienced through the fairy story. This is sobering evidence of the extent to which we humans exist not primarily in relation to the direct input coming ‘bottom up’ from our senses but to our ‘top down’ memories, prior knowledge, and social conditioning.. Understandably, we all crave certainty, and the role played by often uncomfortable, unfamiliar, or complicated facts in furnishing this state is, so it seems, only marginal.

*

And finally, to return to the likelihood of war here on the Korean peninsula, but also, potentially, on a much bigger scale..

As the authors of the 38 North article point out, it’s possible that North Korea will engage in some kind of specific provocation, like when they shelled Yeonpyeong island or sank the ROK navy ship Cheonan in 2010. But as they also write, mad as it may seem, the regime could now be seriously contemplating a tactical nuclear strike. They remind us that ‘North Korea has a large nuclear arsenal, by our estimate of potentially 50 or 60 warheads deliverable on missiles that can reach all of South Korea, virtually all of Japan (including Okinawa) and Guam. If, as we suspect, Kim has convinced himself that after decades of trying, there is no way to engage the United States, his recent words and actions point toward the prospects of a military solution using that arsenal.’

Oh, dear.

Then again, Kim Jong Un and his cronies surely know that a nuclear strike would be signing their own death warrants, even if they have very deep shelters to hide in. They are not a death cult like Hamas and the Jihadists. They do not believe in Paradise. At least, not in one that transcends this world and awaits them when they die a martyr’s death. Kim and Co. already have their ‘paradise’ on Earth. It’s called the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and you can read all about it in the Rodong Sinmun.

NOTES

The image is sourced from: https://m.en.freshnewsasia.com/index.php/en/localnews/44185-2024-01-03-03-18-17.html

The 38 North article can be read at: https://www.38north.org/2024/01/is-kim-jong-un-preparing-for-war/

The BBC article is at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-68052515

The Human Rights Watch data is at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/north-korea

The Rodong Sinmun article, ‘ Report on 9th Enlarged Plenum of 8th WPK Central Committee’, is available at:

The end of the year (or one of them)

Some thoughts on the end of the (or a) year in South Korea, and the bizarre calendar adopted by my neighbors north of the DMZ.

North Korea’s Juche calendar for 2010.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juche_calendar#/media/File:North_Korea_(5015886634).jpg

It's interesting to consider the similarities and differences between South Korean and British attitudes to the Christmas holiday that has just passed. As in my homeland, some Koreans will have celebrated it as a religious occasion, going to church and so on. After all, 28% are now Christian. Nevertheless, I’m sure even the faithful are likely to have embraced the event for what it now truly is: a celebration of consumer capitalism. But one of the great solaces of living here is that Christmas is a far less gaudy obstacle to surmount than it is back home. One has to endure the usual execrable Christmas-themed pop music in all the cafes, but life does not ground to a halt under the weight of Santa and his toy-and-commodity laden sleigh as it does in Great Britain.

*

I’m living in a country when there are two New Year’s day each year.The latter is approaching fast, while the former isn’t until what in the former’s calendar is called February 10th. But last year it was on 22nd January. This is because the traditional Korean calendar is ‘lunisolar’, that is, calculated in relation to the cycles of the moon not the sun.

It used to be that way in Europe too. The shift in the arrangement of time away from the moon to bring it closer to the more regular cycle of the solar year occurred under the Roman Empire in 46BC when it was mandated by Julius Caesar – hence its name, the ‘Julian Calendar’. In 1582, the “Gregorian Calendar’, named after Pope Gregory XIII, was introduced. This is still the one we use today. (The main change was in the spacing of leap years to make the average calendar year 365.2425 days long, which even more closely approximates the 365.2422-day of the ‘solar’ year.) But it wasn’t until as recently 1752 that the beginning of the year was officially moved from March 1st to January 1st.

All this history pertains, of course, to Europe alone, or at least it used to. Pre-globalization, in pre-modern Korea as in the other Chinese influenced countries of East Asia, a lunisolar calendar was traditionally employed called the Dangun calendar. In South Korea, this still remains the basis on which the dates of holidays and commemorative events are calculated, such as the Buddha’s birthday and Chuseok. So, South Koreans essentially live according to two significantly different systems for organizing the passage of time over the course of a year. Like so much else, this reflects the nation’s efforts to absorb Western culture while maintaining ties with indigenous and regional tradition.

*

Also note that the universally agreed-upon conventions for calculating when to begin counting the years is welded solidly to Christianity. It’s 2024 next year because Jesus Christ was born 2024 years ago according to the Gregorian calendar. Hence the fact that the convention is to date events as BC – ‘Before Christ’ – and AD – ‘Anno domini.’ This means that every time we use the normal system for structuring time, we are tacitly placing the Christian religion at the centre of our timekeeping. Critical awareness of this rather obvious bias is why we are now inclined to write BCE – ‘Before the Christian Era’ – and ‘CE’ – “Christian Era.’ But this subtle shift in nomenclature only very marginally decenters Christianity.

Whoever controls the measuring and naming of time, controls society, which is why those in a hurry to change it, also change the calendar. After the French Revolution of 1789 AD (in the Gregorian calendar) a ‘Republican Calendar’ was adopted, the aim of which was to liberate the citizens of France from tutelage to the timekeeping of the royalist Ancien régime and the bane of Christian religion. But such was the chaos of the times that the leadership could never agree when Year 1 actually began, and so it was regularly amended! Once a convention as practical and vital for social interaction as the calendar is deep-rooted it proves impossible to uproot. Imagine the confusion if, say, the critical race theorists or another so-called ‘wokeist’ factions sought to shift the organization of the calendar to better reflect their pressing concerns.

It was in a similar attempt to forge an independent and ideologically controllable timekeeping system that in 1997 North Korea adopted a calendar known as the Juche calendar. Year-numbering begins with the birth of the first leader, Kim Il Sung, which is 1912 in the Gregorian calendar, and so is called Juche 1 in the Juche calendar. This means that by my calculation we’re now living in Juche 123, and soon will be in Juche 124, although not until April 15th, Kim’s birthday. The DPRK, at least officially, has therefore abandoned both the traditional lunisolar and the Western solar calendars. But in practice, there are 3 New Years every year, as North Koreans apparently recognize the Western New Year, the Lunar New Year, and the Juche New Year. This seems rather greedy. But whichever New Year it is they all begin with the same obligation: you must first lay flowers at the bronze statues of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il at Mansudae Grand Monuments in Pyongyang, and statues sited elsewhere throughout the nation.

We can assume with some certainty that the hope for a brighter or better New Year, according to all three calendars, is extremely slim for the children of today’s average North Korean parents, or even those of the elite. However, through adopting a perverse version of historical consciousness that flattens the past to the mere dozens of years since 1912, the regime instills in the people a model of history in which the Kim ‘dynasty’ assumes absolute power over past, present, and future. The goal is to delude them into believing that their children’s better and brighter future is guaranteed – but only if they accept repression by the current regime. For someone to actually believe this brutal canard must require an extraordinary level of cognitive dissonance. But probably only as elevated as the dissonance required for an American to believe Donald Trump should be the next President of the United States!

NOTES

For more on celebrating New Year (or Years) in North Korea, visit: https://www.uritours.com/blog/north-koreans-celebrate-new-years-3-times-in-one-year/

Decay

The picture above was snapped recently while out walking the dog. What you see is a detail of a metal signboard that has been corroded and invaded by ivy tendrils. How long has it undergone this attrition? Difficult to say, but probably not that long. But the only reason it’s there is because it belongs to an abandoned property, and no one has gotten round to removing it. One reason I took the photograph is because It’s unusual to find such beautifully worn surfaces here in South Korea. Everything looks new, that is, without history. Why is this? This questions is especially interesting for me because I really find that such surfaces carrying the random textures of time very poignant and aesthetically pleasing. Koreans, on the whole, don’t seem to have an aesthetic sensibility attuned to enjoying such time-textured surfaces. Why?

The picture above was snapped recently while out walking the dog. What you see is a detail of a metal signboard that has been corroded by the weather and invaded by ivy tendrils. How long has the signboard undergone this attrition? Difficult to say, but probably not that long, and the only reason it’s still there is because it belongs to an abandoned property and so no one has gotten round to removing it.

One reason I took the photograph is because It’s unusual to find such time-worn surfaces here in South Korea. Everything looks new, that is, without a history. Why is this? This question is especially interesting to me because I find surfaces like this that carry the random textures of time very poignant and aesthetically pleasing. But Koreans, on the whole, don’t seem to have a sensibility attuned to enjoying such surfaces. Why?

Koreans seem to have a different sense of time, or of how quickly the ‘past’ becomes the ‘old’. In this context, the word ‘old’ implies the moribund, redundant, diminished, and lacking in economic value. In short, there’s nothing appealing about being ‘old’. Is this why almost all Koreans dye their hair black as they age? As grey hair is a primary signifier of being ‘old’, it’s not something a society bent on the ‘’young’ and the ‘new’ wants to display. In fact, one could say that Koreans strive very hard to erase any signs of age – both in themselves and their built environments. The lifespan of a new building is deemed to be around thirty years. I will never forget the day ten years go when some young acquaintances of my wife said they lived in an ‘old’ apartment. When I asked when it was built, they said, in the 1980s! Koreans always buy new cars regularly. Vintage clothes and second-hand goods in general are not appealing. They don’t want something ‘used’ or, as the current euphemism has it, ‘pre-loved’ (ugh!)

One reason for the animus against the past is that for Koreans it is perceived as traumatic. The first half of the twentieth century was a disaster for their country. The Korea of the second half of the century experienced rapid economic progress, but while this economic development brought immense benefits, it also, in a sense, inadvertently consolidated what Japanese colonial rule had begun: the severing of modern Korea from its rich and unique past.

Where I come from, old weathered surfaces are common. We live surrounded by tangible traces of the past in our built environments, with stones and bricks which endure for centuries. Our ‘modernization front’, as the Swiss philosopher Bruno Latour describes it, advanced much more slowly than here in Korea. The Industrial Revolution was, by comparison, an ‘Industrial Evolution’. It began tentatively in the mid-eighteenth century in England, and so the replacement of the ‘old’ by the ‘new’, the superseding of what was deemed obsolete and redundant, occurred over a much longer period of time and has been far less total. Korea’s economic ‘miracle’ only goes back three generations. It also occurred in what was virtually a tabula rasa – a ruined country decimated by colonial rule and war. After 1953 and the cessation of fighting, there literally wasn’t much ‘old’ Korea left standing.

The westernizing modernization that South Korea embarked upon is premised on the idea that history has a single and developmental direction heading from the past through the present to the future. Consequently, the people of the present must escape the pull of the past on the journey to the future. As Bruno Latour writes in a context that assumes a western reader but which when read here seems to speak directly to the South Korean situation:

What had to be abandoned in order to modernize was the Local…….It is a Local through contrast. An anti-Global. …Once these two poles have been identified, we can trace a pioneering frontier of modernization. This is the line drawn by the injunction to modernize, an injunction that prepared us for every sacrifice: for leaving our native province, abandoning our traditions, breaking with our habits, if we want to ‘get ahead,’ to participate in the general movement of development, and, finally, to profit from the world.

For a nation bent on modernization, the Local is equated with the ignorant, the antiquated, the redundant, the valueless. With failure. In this sense, we can perceive the worn surface pictured above as a sign of the Local that is abandoned because it carries the stain of an archaic past that must be erased as society moves forward into the better future. And, in a rapidly modernizing country like South Korea, ‘the archaic past’ can be very recent history - just a few years ago.

But this doesn’t of course mean that modern-day Korea has no past. What it means, however, is that this past can only exist as pre-packaged and scrubbed clean heritage. ‘Old’ historical buidlings are often modern recreations, like Gyeonbokgung Palace in Seoul, which is a kind of ‘zombie’ palace, in that it has all been recently rebuilt and therefore seems lifeless – although people love to go there dressed up in rented pretend hanbok costumes and use it as a backdrop for their selfies. In my experince, historical buidlings in Korea mostly lack aura - by which I mean, a distinctive atmosphere or quality that seems to surround and is generared by them. But this might just be because I’m not Korean. Or, it might be because aura isn’t something that can be consciously produced or manufactured. In relation to built structures, it’s a kind of spatial resonance that is associated with the time-worn, the random, the unproductive, the neglected.

The contemporary Korean animus against the ‘old’ is rather surprising, however, insofar as South Korean society still also clings to the conventions of Confucian age-hierarchy, which means different forms of language are necessary when talking ‘up’ to older people and ‘down’ to younger. It’s normal for Koreans to say in English that someone is a ‘junior’ or a ‘senior’ in relation to them, which sounds odd to westerners. One of the first questions a Korean will ask you is your year of birth; this is so they know if you’re a ‘senior’ or a ‘junior.’ They also venerate their ancestors. And yet…..

*

How to have a living relationship with the past? One way is to consciously live with it’s traces. Without them, how can one exist in anything but a shallow present? This might have been sufficient when the future seemed to be a golden invitation. Today, it is not. So, we end up stranded in a present divested of both the appeal of the Local and the Global.

Bruno Latour’s discussion in the book from which I have quoted, unfolds within what he terms the ‘new climatic regime’, by which he means the crisis caused by humanly-engineered climate change. Latour argues that the old binary of the ‘attractors’ Local and Global which dominated the modern period (and determined South Korea’s modern identity) cannot permit us to confront the challenges of the Anthropocene. Instead, these poles need to be linked to a third, which Latour calls the ‘Terrestrial.’ By this, he means the ‘attractor’ of Planet Earth itself.

It seems to me that living surrounded by time-textured and humanly-made surfaces is one important part of being Terrestrially-minded. These traces remind us of our finitude. Ultimately, they are memento mori. They show us that everything decays and passes away.

NOTES

My quotes come from: Bruno Latour, Down to Earth. Politics in the New Climatic Regime, translated by Catherine Porter (Polity Press, 2018)

Mimicking America

Today is Halloween, and here in South Korea young people will be celebrating. But why?

Today is Halloween, and here in South Korea young people will be celebrating. I snapped this rather sad-looking photograph recently at our nearby ‘dog café’ which has installed the typical Halloween merchandise for its clientele, who come from the apartment towers of greater Seoul to give their dogs a run-around in a safe countryside setting, complete with piped K-pop music, a swimming pool (for the dogs), and comfy chairs and cups of coffee (for the humans).

This time last year, there was tragedy in Seoul when huge numbers of people gathered to have fun on Halloween and 151 were crushed to death in a narrow alley in Itaewon. This year, there won’t be any tragedy there, because people will steer clear of the area and the police will be much more vigilant. But in this post I want to ask a simple question: ‘What the Hell are South Koreans doing celebrating Halloween?”

Let’s start with some history. What is Halloween? The History Channel explains:

The tradition originated with the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, when people would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off ghosts. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as a time to honor all saints. Soon, All Saints Day incorporated some of the traditions of Samhain. The evening before was known as All Hallows Eve, and later Halloween. Over time, Halloween evolved into a day of activities like trick-or-treating, carving jack-o-lanterns, festive gatherings, donning costumes and eating treats.

And this is what the website of an (American) company called Gourmet Gift Basket informs us about Halloween’s metamorphosis into a modern-day (and for Gourmet Gift Baskets, very lucrative) event:

American colonists are responsible for initially bringing Halloween to the United States. Most of the colonists were English Puritans who celebrated Samhain before traveling to their new Country. Although the Celtic religious traditions had long been replaced by Christianity, many of the old practices remained. Influenced by a variety of cultures, the Halloween traditions in the American Colonies began to meld and change.

In the New World, All Hallow’s Eve became a time for “play parties”, which were private parties thrown to celebrate the harvest. Many dressed in costume and told scary stories. These first Halloween parties helped shape the history of Halloween into the celebrations we have today!

In the mid-1800s, Irish immigrants came to the United States, bringing their Halloween traditions with them. This included dressing up in costumes, asking their neighbors for food and money, and pulling pranks in the evening on Halloween. Americans started doing the same thing, which eventually turned into what we now know as trick-or-treating. However, it wasn’t until recently that treats became more common than tricks.

For Example, In the 1920s, rowdy pranks had become expensive and costly, especially in major cities. Over time, cities and towns began organizing tame, family-oriented Halloween celebrations, which eventually helped reduce the number of reported pranks. Once candy companies began releasing special Halloween-themed candies, our modern idea of “trick-or-treating” was born.

Halloween, as we know it today, is one of our oldest holidays. It wasn’t always celebrated in the United States, but it has become an important and fun part of our culture. So, we can’t think of a better way to celebrate than by sending Halloween gifts. Because at GourmetGiftBaskets.com, it’s what we do best!

I remember as a child in England in the 1960s also enjoying Halloween. But we didn’t do the ‘trick-or-treat’ thing. We used to play ‘Murder in the Dark’, a game with a fabulous name but whose rules I can no longer remember. I seem to recall knowing that Halloween wasn’t something that we traditionally celebrated in England. I certainly didn’t know back then it originated from Ireland (even though my mother’s family were Irish immigrants); in fact, I didn’t realize it had Celtic roots until I started researching this post. Back then, I vaguely sensed Halloween was an American import, which is closer to the truth: despite the ‘Celtic’ gloss, Halloween is obviously an overwhelmingly American thing, and this is why young South Koreans also celebrate it.

Halloween is, one could say, a bizarre dimension of the pervasive and hugely successful cultural imperialism of the United States of America.

Actually, this is one of the reasons why living in Korea has been relatively easy for me, a Westerner. As a Brit growing up in Eastbourne, a small seaside town on the south coast, I discovered I shared this imperializing experience with my future Korean wife who was growing up in northern Seoul.

When I was sixteen, I brought a pale blue sweatshirt with the logo of the University of California on it. Why? Because it was cool. It symbolized something glamorous.. I took to wearing Levi jeans, which I had to make a pilgrimage to a shop in the nearby and more cosmopolitan town of Brighton to purchase (I still wear Levi’s – in fact, by very good fortune there’s a Levi’s store in the nearby Lotte Outlet shopping complex!). Back then, I listened mostly to American music (although we Brits had our fair share of pop stars) and watched mostly American tv and movies. But to call this influence ‘cultural imperialism’, as my left-leaning and inherently anti-American adult mindset encourages me to do, fails to confront the fact that what I’m referring to is more like a ‘romance.’ If I’ve been colonized, it’s because I wanted to be colonized.

For the British, this romance began during World War Two (when the American GI’s were ‘over paid, over sexed, and over here’) and was propelled by a bullish Yankee dollar and overwhelming American confidence in their nation’s destiny to be guardian of the ‘free world.’ For my wife and South Koreans, the romance began after World War Two and went into turbo-drive after the Korean War. Nowadays, South Korea is by far the most Americanized East Asian country.

So, what is so ‘romantic’ about America? David Hockney, the British Pop artist emigrated to California in 1964 and later wrote: ‘Within a week of arriving….in this strange big city, not knowing a soul, I’d passed the driving test, bought a car, driven to Las Vegas and won some money, got myself a studio, started painting all in a week. And I thought: it’s just how I imagined it would be.” ‘Just as I imagined it would be.” I know what Hockney means! New York City was ‘just as I imagined’ when I moved there in 1983 (I stayed for three years). America was so familiar because we’d absorbed it through the mass media. We’d absorbed it willingly and easily because it was so appealing. America seemed so free, so unburdened by the past, so unlike staid, repressed, grey England. It is this promise of freedom that we all desire by becoming ‘trainee’ Americans. I recall when I lived in New York having very strongly the sensation that everything was potentially within my reach, whereas in England it had felt many things were not, due to class, and my small-town background. Being ‘American’ meant nothing less that becoming truly modern and free.

The first thing I noticed when I arrived in Tel Aviv as a very immature eighteen year old going to work on a kibbutz, was a big Coca-Cola sign written in Hebrew script. This still sums up for me the pull and reach of American culture. It seems so easy to translate into every world language. It’s a kind of cultural Esperanto. But how does it succeed in being so democratic? Because it is the lowest-common denominator? American culture is almost synonymous with consumer capitalism and neoliberalism. On a material level, practically everything is American (though not manufactured there): this Apple computer I’m working on, the clothes I wear, the food I often eat (even in Korea), the social media networks I use. But you can’t really be a diligent consumer – or even just a person of the modern world - without also embracing a state of being that we could call ‘Americanness’. In Sapiens. A Brief History of Humankind, the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari writes:

The capitalist-consumerist ethics is revolutionary in another respect. Most previous ethical systems presented people with a pretty tough deal. They were promised paradise, but only if they cultivated compassion and tolerance, overcame craving and anger, and restrained their selfish interested. This was too tough for most……In contrast, most people today successfully live up to the capitalist-consumerist ideal. The new ethic promises on condition that the rich remain greedy and spend their time making more money, and the masses give free rein to their cravings and passions – and buy more and more. This is the first religion in history whose followers actually do what they are asked to do. How, though, do we know that we’ll really get paradise in return? We’ve seen it on television.

Of course, America isn’t paradise. As I grew older, I learned to question the Americanizing imperative. But this often meant focusing on the American ‘nightmare’, on all the ways it patently fails to be the paradise it advertises itself to be: the appalling inequalities in wealth, the racism, the violence, the dysfunctional democratic system, the superpower overreach, et. etc. But this obsession merely reinforces the fact that whatever we might think of the real America, the one that’s implanted in our imaginations – in the global collective imagination – is overwhelmingly compelling because it syncs so perfectly with the socio-economic reality of modern, ‘developed’ societies.

The English writer Martin Amis wrote a book called ‘The Moronic Inferno’, published in 1986. It’s a collection of essays about America that are so entertaining because Amis is simultaneously appalled and enamored by his subject. He wrote: “I got the phrase ‘the moronic inferno’, and much else, from Saul Bellow, who informs me that he got it from [the English writer and artist] Wyndham Lewis. Needless to say, the moronic inferno is not a peculiarly American condition. It is global and perhaps eternal. It is also, of course, primarily a metaphor, a metaphor for human infamy: mass, gross, ever-distracting human infamy.”

There is a steep price to be paid for enjoying this cultural lingua franca. The Japanese philosopher Ueda Shitzuteru calls it the “hypersystemization of the world” - the deadening unifying cultural uniformity imposed by American-stye consumer capitalism, which is “bringing with it a swift and powerful process of homogenization that is superficial and yet thorough-going”. We live, declares Ueda, in a “mono-world which renders meaningless the differences between East and West”. This ‘hypersytemization’, as Amis noted, also has an ominous, apocalyptic dimension because the United States is a superpower equipped with nuclear weapons: ‘Perhaps the title phrase is more resonant, and more prescient, than I imagined. It exactly describes a possible future, one in which the moronic inferno will cease to be a metaphor and will become a reality: the only reality.”

We wince at the crassness of American culture, it’s deep superficiality, but we cannot escape its profound allure. I guess people living under Roman rule might have felt a similar compulsion to mimic Roman manners and ways of thinking - the manners of the rulers. It’s a form of assimilation, but also of being on the right side of history: the winning side. However much China might challenge America economically, it has already been colonized culturally simply by adopting consumerism. There are very few places left one Earth that have not been colonized. One of them lies just a few miles north of where I write this post. However much we might cringe at what America has become – as if the kind and encouraging Uncle Sam has turned into a serial rapist and murderer - there’s still nowhere else that can enchant like the idea of America.

NOTES

The quote from Gourmet Baskets is from: https://www.gourmetgiftbaskets.com/Blog/post/history-halloween-united-states.

The quote from the History Channel is from: https://www.history.com/topics/halloween/history-of-halloween

The David Hockey quote is from: https://www.thedavidhockneyfoundation.org/chronology/1964

Martin Amis’ book can be purchased at: https://www.amazon.com/Moronic-Inferno-Other-Visits-America/dp/0140127194

Yuval Noah Harari’s book can be purchased at: https://www.amazon.com/Sapiens-Humankind-Yuval-Noah-Harari/dp/0062316117

MBTI. Some more thoughts

Some more thoughts on the MBTI craze in Korea, and its relationship to modernization in general.

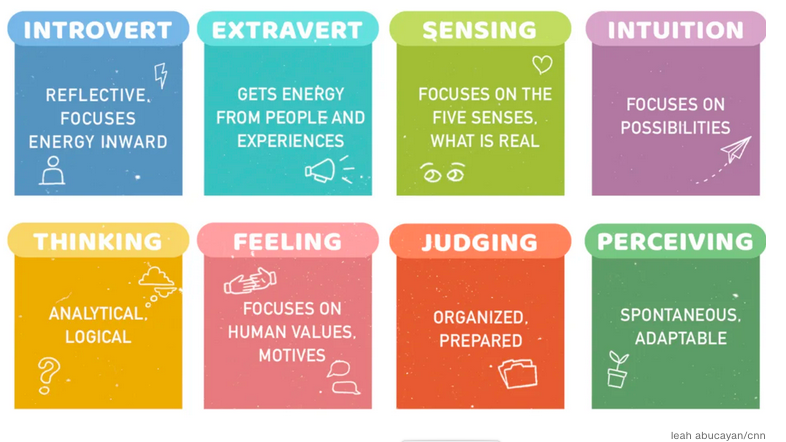

A screen-grab from the website ‘16Personalities’ - one of the most popular in South Korea for learning about MBTI.

In the previous post I discussed young Korean people’s enthusiasm for MBTI personality profiling and argued that one of the reasons why MBTI has become so popular here is that it provides the possibility of organizing the messy reality of human identity in an efficient manner that draws attention only to positive character traits.

In this post I want to dwell on the word ‘efficiency’ and its role in Korean society. I think there’s no doubt that visitors to the Republic of Korea are likely to be struck by the feeling that this country is highly efficient. I don’t think I’ve ever waited for a subway or mainline train because it’s late. The country has the fastest broadband internet connection. When Koreans decide to emulate something foreign they always seem to do it with greater efficiency.

The contrast between the contemporary inefficiency of Western European societies (the ‘Wild West’, as I like to call it nowadays) and the ROK’s obvious efficiency was especially striking during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the recognition has stayed with me even after things are moving back to some kind of ‘normal’.

This ‘efficiency’ is all the more striking because in the early days of contact with the West and the initiation of modernization first under the Japanese, and then under the watchful eyes of the military government between the 1960s and 1980s, it was precisely the nation’s inefficiency that was criticized – both by foreigners and by Korean modernizers. Ahn Sang-ho (1878 – 1938), a prominent politician and independence activist under Japanese colonial rule, one of the first Koreans to emigrate to the United States who then in 1926 returned to Korea and engaged in anti-Japanese activism for which he was imprisoned - an experience that led to the ill health that caused his death - deplored Koreans’ parochialism, depravity, laziness, and dependence.

Ahn called for a radical reform of social behaviour through education and self-cultivation, but the spirit of modernization he admired in the West, which had led to the exponential expansion of the West’s wealth, power and influence, and the establishment of a democratic political system, was also fundamentally driven by what the German sociologist Max Weber (1864 – 1920) termed ‘bureaucratization’. This involved the organization of Western society around functional, formal, rational systems with well-defined rules and procedures. It required hierarchy, specialization, training, impartiality and managerial loyalty. A society moved through rationalization towards greater efficiency and effectiveness, and this in its turn meant that the citizens would reap the benefits in terms of greater security and wealth. But Weber warned that excessive reliance on and adherence to rules and regulations also inhibited initiative and growth. The tendency is for a managerial-bureaucratic society to treat people as machines rather than individuals. In other words, the system is de-humanizing. There is the danger that emotions and feelings are not incorporated into the way a bureaucratic society is run. The impersonal approach to the organization of a society shunts these dimensions of human existence to the margins, dismissing them as obstacles to social efficiency. For Weber, the systematic ‘dis-enchantment’ of the world was the price of rationalization. Technological expertise replaced priestly vision, and rationality and efficiency replaced mystery and magic.

Is it too much to say that in its avid desire to join the ranks of modernized nations, the ROK adopted a version of the Western bureaucratic model, one that from the 1970s onwards proved to meld very effectively with elements of pre-modern Confucianism, such as social hierarchy and the sense of the community as a collective rather than made up of individuals? Is it too much to suggest that young Korean’s weakness for MBTI today is a side-effect of the excessively bureaucratic version of capitalist modernization adopted by the ROK, manifested on the level of questions pertaining to personal identity?

Another screen-grab from 16Personalities.

*

In the previous post I mentioned the cultural theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, members of the so-called Frankfurt School and exponents of ‘critical theory’ – critical’ being the key word. For these left-leaning German Jews, writing in the wake of Hitler’s rise in Germany and Stalinism in the Soviet Union, its seemed that modernization in general was fundamentally unhinged. They believed the seemingly ‘open’ and democratic United States was simply more insidiously ‘fascistic’ than the obvious culprits. Capitalist modernity was synonymous with the degradation of human life to a level where the experience of alienation from the world and from each other was pervasive. Building on the social theory of Weber and others, they diagnosed modern society as having shrugged off one metaphysical system for another – religion for rationality.

In the more recent writings of the Frankfurt School sociologist Hartmut Rosa, which I have also mentioned in an earlier post, the uncompromisingly bleak prognosis of Adorno and Horkheimer cedes to a more nuanced perspective on the price of modernization. Alienation is still the norm, but Rosa stresses that modernization is also unique in seeking multiple remedies for alienation. One such remedy is art. Others include pop music and getting drunk or high - anything that can perhaps deliver the antithesis of alienation, which Rosa calls the experience of ‘resonance’. This benign world-relating to which Rosa refers is fugitive, structureless, and inherently invisible. “[R]esonance is not an echo, but a responsive relationship, requiring that both sides speak with their own voice”, Rosa writes in Resonance. A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World (2019). It is precisely because of the anti-structural properties of resonance that it is so highly valued and desired, because ultimately what is at stake is our profound yearning for a relationship to the world that is without hierarchy, divisions, and boundaries, in which we feel a deep sense of sharing, intimacy and harmony, and where all people and things are equal. Rosa’s choice of the term ‘resonance’ is largely determined by its anti-structural nature, and indicates that benign relationships with the world involve responsiveness on both sides – of the subject and the world. For Rosa argues that “resonance appears not as something that first develops between a self-conscious subject and a ‘premade’ world, but as the event through which both commence”. The experience of resonance can therefore only potentially occur when there is “a relation between two bodies that are at once open enough for a relationship while at the same time remaining sufficiently stable and closed so as to ‘sound’ at their own frequency or ‘speak with their own voice’.”

Rosa sees all people in developed countries as living lives mainly of alienation, and considers this to be primarily because modernity is inherently about aggressive control. As Rosa puts it in his most recent work to be translated into English, The Uncontrollability of the World (2020): “Modernity has lost its ability to be called, to be reached” becausewithin in it “[w]e are structurally compelled (from without) and culturally driven (from within) to turn the world into a point of aggression. It appears to us as something to be known, exploited, attained, appropriated, mastered, and controlled. And often this is not just about bringing things – segments of world – within reach, but about making them faster, easier, cheaper, more efficient, less resistant, more reliably controlled.” Rosa sees four dimensions to modernity’s obsession with guaranteeing maximum control which thwart the possibility of achieving resonance: the world is made visible and therefore knowable by “expanding our knowledge of what is there”, the world is made physically reachable or accessible, manageable, and the world is made useful. As a result, the price of achieving a historically unprecedented degree of control is that the modern subject exists mostly in a condition of profound alienation, inwardly disconnected from other people and from the world.

It seems to me that the contemporary Republic of Korea is especially prone to this rage for control, and that the craze for MBTI is one manifestation of this overwhelming tendency which is an intrinsic part of the modernization process through which the ROK has gone at breakneck speed. As Rosa writes: “Modernity stands at risk of no longer hearing the world and, for this very reason, losing its sense of itself.”

In a future post I will consider how MBTI can also be understood within a broader Korean historical and cultural context that predates Westernization. I will also explore how in the West the alientation of which Rosa writes plays out in terms of a lack of the very secure identity sign-posts that MBTI provides Koreans, and is causing so much trouble. Perhaps the South Koreans may be recognizing something important we in the West are not…...

References

The image at the beginning of today’s blog is from: https://www.16personalities.com/country-profiles/republic-of-korea

Max Weber’s ideal type of bureaucracy was described in Economy and Society, published in 1921.

Hartmut Rosa’s books are Resonance. A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, translated by James C. Wagner, and published by Polity Press in 2019, and The Uncontrollability of the World, also translated by James C. Wagner, and published by Polity Press in 2020..

Korea goes crazy for MBTI

Last week in class, one of my students mentioned how Koreans her age (the so-called MZ Generation) are seriously into MBTI – the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator personality assessment test. As I soon discovered on trawling the Internet, MBTI is practically an obsession amongst the young here in Korea. Why?

Last week in class, one of my students mentioned how Koreans her age (the so-called MZ Generation) are seriously into MBTI – the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator personality assessment test. As I soon discovered on trawling the Internet, MBTI is practically an obsession amongst the young here in Korea.

So, what is MBTI? It was devised in 1943 in the United States by a mother-daugher team, Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs-Myers. They were inspired by Carl Jung’s analytic psychology, but neither had professional training in psychology. This didn’t stop their personality assessment questionnaire taking off. It appealed to anyone who wanted simple answers to very complex questions, a clear map to the wilderness of the human mind. MBTI was therefore appealing to huge corporations and confused teenagers.

These are the basics personalities you can choose from:

The eight basic types combine to produce 16 composites, ranging from ISFP (Introvert-Sensing-Feeling-Perceiving) which make you kind, spontaneous, and accommodating, to ENTJ (Extravert-INtuitive-Thinking-Judging), which means you are confident, innovative, and logical. Of the latter, the website Truity, which has the by-line ‘Understand who you truly are’, says that it ‘indicates a person who is energized by time spent with others (Extraverted), who focuses on ideas and concepts rather than facts and details (iNtuitive), who makes decisions based on logic and reason (Thinking) and who prefers to be planned and organized rather than spontaneous and flexible (Judging). ENTJs are sometimes referred to as Commander personalities because of their innate drive to lead others.’

Here is the full menu:

If only it was so damn simple! Jung must be turning in his grave. He is on record as saying that MBTI profoundly misunderstood his analysis of personality. First of all, the assumption of MBTI is that you have a stable, fixed personality that is fully accessible to conscious self-reflection, that we are objective in our appraisal of our own personality traits. Secondly, you will note that according to Myers-Briggs, everyone’s personality is basically comprised of positive traits. This is very far from the thinking of the man who urged us to descend deep into the murky darkness of our consciousness, where we must face our ‘shadow’. As Jung wrote: ‘Unfortunately, there can be no doubt that man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself to wants to be.’ It is also obviously very different from the prognosis of Jung’s mentor and then rival, Sigmund Freud, concerning human nature (think, Oedipus Complex, the ID, and the Death Instinct).

MBTI is a sanitized, feel-good bowdlerization of very complex modern, but now dated, insights into the human psyche. In fact, if it wasn’t such an influential test, one might dismiss it as innocent fun, like astrology. And now, eighty years after it was first devised, and on the other side of the world, MBTI has been especially adopted by South Koreans. They are far and away the most avid adopters of the test, and the MBTI categories are routinely used in formal and informal social situations, and as a dating tool. Why?

There are several obvious reasons. Above all, perhaps, there is the influence of Korea’s collectivist social structure. This inclines individuals to seek to identify themselves not as independent, unique, selves but as members of clearly defined groups. In other words, as I noted in a previous post, when considering their identity, Koreans tend to struggle to associate their private self with a publicly recognizable self. But MBTI facilitates this by providing sixteen clear personality types. As Sarah Chea writes in the Korea JoongAng Daily: ‘Koreans tend to easily feel anxious when they think they don’t belong to any groups, so they push themselves to be involved so they can belong somewhere. They like to feel the sense of community from being with others in the same group, and feel relief when they feel they are not alone.’

Then there is the fact that Covid-19 pandemic accentuated people’s sense of isolation, making young Koreans even more desirous of connecting with others through explicit shared criteria concerning identity. Social media made this possible, but also required radical simplification. It’s much, much easier to say ‘I’m ESFJ’ than to struggle with the vague and shifting reality of one’s personality. But only, of course, if one is confident whoever is reading knows what you mean. MBTI therefore also serves to establish clear in-group/out-group boundaries not just within the 16 different personality types but in relation to assessing people in terms of those who have adopted the MBTI vision as a whole and those who have not.

This desire to share one’s personality with others is surely motivated by the need to feel less alone, but also by the fact that we now live in a culture in which self-realization is highly valued. The era we are now living through has radically altered how we think about ourselves, making the private self a ‘bankable’ commodity. But as the philosopher Han Byung-Chul notes, the deepest problem for people in the developed world is excessively positive attitudes which lead to a pervasive failure to manage negative experiences. This is surely another reason why MBTI is appealing. It allows us to gesture towards the interiority required of the fully contemporary identity while seeing ourselves only in relation to positive personality traits.

If we look at MBTI historically, we can recognize that it was born during a period in the United States when there was a drive towards the instrumentalization and rationalization of society in the service of the bureaucratic thinking central to a managerial capitalism, and tied to the immediate need to optimize efficiency for the war effort. As noted by the Frankfurt School thinkers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer – who when Myers and Briggs-Myers devised MBTI were living in the United States in exile from Nazi Germany – instrumental reason privileges the objective at the expense of the subjective, and obscures the fact that so-called ‘reason’ is always a mix of the rational and the irrational, the subjective and the objective. As a result, the objective is viewed as unchanging, eternal, and universal.

This is precisely what MBTI does in relation to personality and identity. Which means Koreans are placing the need for ‘efficiency ‘ in relation to achieving their ends above all other possible motives and desires. They are coping with the hyper-novelty, stresses and strains of accelerated modernization and westernization in their country by resorting to a blatant example of objective, instrumental reason, deployed in relation to the intimate and vulnerable region of their inner experiences - their personalities where, in reality, subjective experience reigns. This will surely inhibit any genuine exploration of identity. As Jung wrote: ‘The darkness which clings to every personality is the door into the unconscious and the gateway of dreams.’

By channeling the desire to present one’s private self in public without risk, through sanitized publicly accessible categories, MBTI is certainly a useful tool of social conformity. It is a million miles away from the profound crisis of identity evident in the West’s preoccupation with gender dysphoria. So, perhaps I am being too negative. In this cultural light, perhaps MBTI is a valid means of ensuring social stability.

Or perhaps most young Koreans think of MBTI as just a fun way of referring to each other, a game, and take it all with a big pinch of salt.

SOURCES:

The MBTI tables are from: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/22/asia/south-korea-mbti-personality-test-dating-briggs-myers-intl-hnk-dst/index.html

Truity quote: https://www.truity.com/personality-type/ENTJ

Korea JoongAng Daily quote: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2022/04/16/why/korea-mbti-blood-types/20220416070206510.html

Han Byung-Chul’s views can be found, for example, in The Burnout Society (Stanford University Press, 2013)

Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s ideas concerning ‘instrumental reason’ can be found in Critique of Instrumental Reason (Verso, 2013)

Carl Jung’s writings are voluminous. A good place to start is Modern Man in Search of A Soul (1936) which is available in a new edition from Routledge. The Amazon blurb is telling: ‘One of his most famous books, it perfectly captures the feelings of confusion that many sense today. Generation X might be a recent concept, but Jung spotted its forerunner over half a century ago. For anyone seeking meaning in today's world, Modern Man in Search of a Soul is a must.’

The Bully (Part 2)

Three bullies from the same Korean family.

There are two versions of ‘modern Korea’. One is ruled by the most autocratic dictatorship today - which makes Putinism look very amateurish - while the other has just elected a new President coming from the political party that had previously been in opposition. Two radically different systems developed, starting with the same circumstances and the same people. One Korea seems to have used Nineteen Eighty-Four as its guidebook, while the other started out with an authoritarian regime but evolved into an American-style liberal democracy. This situation has nothing to do with intrinsic ‘Korean’ proclivities. How can it? The same ethnic and historically extremely homogeneous people have gone very separate ways, like identical twins separated at birth.

One explanation of this bizarre and tragic siutuation is to see Korea not in isolation but as holistically connected to everything else going on in the world, and so to more or less random factors. Specifically, in 1945 Korea had the misfortune of being a colony of the defeated Japanese, and so was carved up by the two victorious forces: the Soviets and the Americans and allies. As a result of the Cold War an Iron Curtain descended across the 38 Parallel. Two nations were created. War ensued. No definitive conclusion to the war was achieved – neither side was wholly vanquished - and so the two rivals Koreas remain to this day. And so here I am, writing my blog near to where the Iron Curtain still remains drawn and looks like staying into the foreseeable future.

But chance factors also extend down from the macro to the micro level. Yes. Korea became a pawn in the Great Power’s struggle for world hegemony. But what happened was also due to individual players on the ground. Specifically, Korean leaders and their entourages. The first President of the Republic of Korea, Sygman Rhee, the American choice, was no friend to liberal democracy. Ostensibly in order to protect the Republic from North Korean aggression (In 1968, for example, North Korean commandos almost succeeded in assassination Park, making their incursion to within a few hundred meters of the presidential Blue House in central Seoul), the South Korean leader, the former army General Park Chung-hee (who had taken control of the state in 1960), suspended the constitution in 1972 declared martial law, and wrote a new constitution that gave him much increased executive power for life. The new constitution would remain in force until Park’s assassination (by his own bodyguard, not the North Koreans) during a military coup 1979, whereupon the military extended its powers of repression even further. In 1980, there was a popular uprising in the south-eastern city of Gwangju which was brutally put down, and most of the 1980s passed under authoritarian rule. However, finally, after the amendment to the constitution in 1987, a democratic presidential election was held for the first time, and since then, elections have been peacefully held every five years.

Why was this possible? Critics will say the United States engineered the semblance of liberal democracy, making South Korea into a compliant a vassal state. But this can’t be true. The level of genuine democracy here cannot be imposed either from outside or above, by fiat. That much we know from history. It must grow from within and below. Which isn’t to say, like some apologist for democracy, that democracy is somehow inevitable. Is certainly is not. Which is one very good reason why democracy needs to be well defended. North of the DMZ, a very different political situation occurred. Things froze into totalitarian place, and this was largely due to the odious bully Josef Stalin and the equally odious bully Kim Il sung and his two progeny. The bullies are certainly there in the Republic of Korea. But the Republic of Korea, like other liberal democracies, devised ways to hem them in, limit the damage they can do.

Steven Pinker marshals plenty of compelling evidence in books such as the better Angels of Our Nature (2011) and Enlightenment Now (2018) to show that history can be read as a narrative in which societies have become increasingly buttressed against the inevitably of zero-sum thinking by creating checks and balances to diminish the chances of a bully getting so much power that he or she can enslave us. This has happened at all levels of society, especially over the past fifty years.

At my grammar school for example, which i mentioned in my previous post on bullies. In the mid-1970s the headmaster of Eastbourne Grammar School changed, and the new headmaster arrived with an updated education philosophy in which the aim was no longer to instil the necessary body of learning through intimidating, and, more profoundly, did not see life as a zero-sum game. There was now enough for everyone. Admittedly, by this time I was sixteen, so I was no longer at the bottom of the bullying pecking-order. But I’m sure what I perceived was generally felt - even by the even-year-old squirts who made up the First Year. The ethos at my school went very quickly from the terroristic to the consensual. You could say it went from totalitarian state to liberal democracy in less than five years. That is no trivial change, and was largely down to the revolution is how people thought about society that happened in the sixties. Obviously, bullying did not disappear. But it was no longer institutionalized, and so could do less harm.

This same process has occurred on the level of nation-states. Look at Donald Trump. He’s almost a caricature of the bully. When he was a reality tv star doing The Apprentice, that was basically his role. And, yes, the show as a hit, because, yes, we enjoy watching bullies at work – as long as they’re bullying someone else. The zero-sum psychology is something like this: if I’m watching someone else getting bullies, then it’s not me. But when he was President of the United States, Trump the Bully - who was largely elected because he was a bully - found he was unable to do what he needs to do as a bully, which is intimidate the vulnerable and keep all the pie for himself. The United States Constitution got in his way. What does this tell us? Yes. I know. The United States is very far from perfect, but it has a political system that is obviously more able to stop bullies than, say, Russia’s. Indeed, all liberal democracies have this in-built capacity. This is real progress, and we should be able to celebrate.

Which leads me back to the point I’ve been making in previous posts: in our eagerness to show how far our liberal democracies are from perfection, we progressives spend a lot of energy exposing their imperfections. In fact, this is precisely one of the main reasons why liberal democracy is the least bad political system: it makes room for criticism and opposition. It knows that if you don’t have freedom of speech and diversity of opinion, you don’t have the ability to stop the bullies. We can’t get rid of them entirely, because they are an aspect of being human. But we can make them less able to freely bully, to bully without consequences. The deeper problem is how to ween us of our primitive admiration for bullies.

To do that, we would have to address a very deep predisposition.

A few years back I was disgusted to discover that my Korean wife’s sister-in-law, who lives in the USA, had voted for Trump. When I asked her why, she replied it was because he was “strong.”

If we want to get rid of the cult of the bully, our acceptance of being bullied, and our collusion with bullies, we will have to change the whole idea of what human ‘strength’ is.

Not easy!

Credits:

Kim photos: https://www.freepressjournal.in/world/kim-jong-un-kim-jong-il-kim-il-sung-why-are-all-north-korean-leaders-named-ki

From ‘developing’ to ‘developed’

Development, South Korean style.

Recently (July 2nd), the Republic of Korea was elevated from the status of ‘developing’ to ‘developed’ nation by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which reclassified it from Group A (Asian and African countries) to Group B (developed economies). This is quite an upgrade. It’s the first since the agency’s formation in 1964. As the website KOREA.net explains: ‘UNCTAD is an intergovernmental agency with the purpose of industrializing developing economies and boosting their participation in international trade. Group A of the organization comprises mostly developing economies in Asia and Africa; Group B developed economies; Group C Latin American and Caribbean States; and Group D Russia and Eastern European nations.’

The South Koreans are understandably very proud of themselves. This is an unparalleled achievement. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953 the Republic’s gross domestic product - the total value of goods produced and services provided in a country during one year - has leapt 31,000 fold! One could say that the concept of ‘development’ is the nation’s mantra, which is enshrined in the commonly used phrase ‘dynamic Korea’.