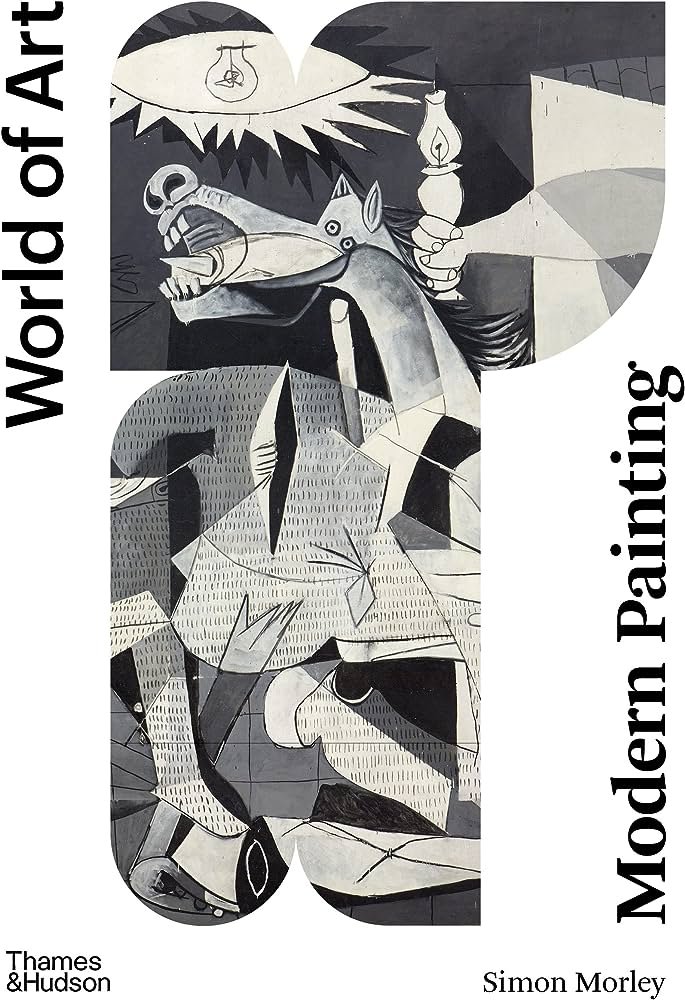

Just published ‘Modern Painting’!

My new book is just published by Thames & Hudson.

I’m back in Korea, and finally over jetlag. Waiting for me when I got home were the author copies of my new book: Modern painting. A Concise History. It’s published by Thames & Hudson as part of their World of Art Series, and is available now in the UK and in October from Amazon.com.

Here is s a sneak preview of the Preface:

It may come as a surprise that the predecessor to the present book in the renowned World of Art series is Sir Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting, first published in 1959, revised by Read in 1968, and finally reprinted with an additional concluding chapter by Caroline Tisdall and William Feaver in 1974. Read’s history assumes without question the importance of painting, or at least some forms of painting, as a vitally ‘modern’ art medium. One of the reasons for the delay in the appearance of a new survey in the World of Art series is that around the time Read published his book, and certainly when it was revised, painting’s status fell into question. The experimental impetus driving art forward, the desire to innovate, seemed to have ended up producing blank canvases, or near enough. At the same time, painting as a medium was condemned by the artistic avant- garde as outdated and too much of a commercial product. Instead, various conceptual practices that were anything but paintings took centre stage. But times have changed. Within contemporary art, paintings in many, many styles have secured valued places alongside a host of other practices that embrace radically expanded ideas about art.

Read began his history with the French artist Paul Cézanne – that is, in the late nineteenth century. This new volume starts about one hundred years earlier, with the emergence of Romanticism in European art. Read’s choice was primarily motivated by the fact that for him the honour of being called a modern painter was only to be awarded to those who made certain kinds of paintings. He argued that it was not enough for an artist to ‘belong to the history of art in our time’ in order to be described as ‘modern’ in the specific way he defined it. His narrative drew a line between late nineteenth-century Post- Impressionism and what came before, as well as a line around types of painting associated with less innovative styles that did not reject the conventions of optical realism forged in the Renaissance. Read saw ‘modern’ art as being geared towards challenging these conventions and dedicated to perpetual innovation – with one style trumping and making redundant what came before as art moved inexorably towards what Read described as the goal of ‘making visible’ rather than ‘reflecting’ the visible (which is what he assumed realistic painters did). In stylistic terms this boiled down to either abstract art and the repudiation of any obvious reference to the visible world, or the dreamlike imagery associated with Surrealism.

This new concise history tells a more inclusive story than Read’s, one that places painting in a broader stylistic, historical, geographical, and gender and ethnic frame. It is structured as a loose timeline. Where it seemed interesting to do so, I have quoted the words of the artists themselves, but I have avoided quoting from critics, theorists and art historians. At the end of the book there is an Appendix in the form of a series of questions that the reader might like to ask of the artists and the ideas discussed, but also of the text itself. This is followed by a Further Reading section for those that want to dig deeper.

I hope this new history allows the artists and paintings it discusses to be appreciated within a diverse and inclusive intellectual, historical and social framework. I am certain that, especially from the perspective of the new plural centres of the globalized

contemporary artworld, the story told in these pages will still look overtly centred on Europe and North America. But the concept of ‘modern art’ was born in Western Europe, and it is inextricably bound up with the forces of westernizing modernity. Furthermore, there is no escaping the fact that ‘‘art history’ as a genre is in itself a fundamentally western discipline invented for organizing cultural artefacts and their relationships within specific categories across time and space.

Finally, I want to stress that there is no substitute for knowledge by acquaintance. Only by seeing real paintings in museums and galleries will we be able to develop valuable relationships with them. This truth is especially important to recognize nowadays, since we are becoming more and more dependent on experiencing the world via digital media. While the Internet allows easy and free access to an unprecedented number of images of paintings, compensating generously the inevitable difficulties involved in seeing real ones, we should always remember that a photograph of a painting is just that, a small-scale, flat, synthetically coloured, digitally generated reproduction. But, more concerningly, a photograph of a painting on a screen or in a book displaces it into a context in which we experience it sitting down within the kinds of spaces that encourage the more cerebral or intellectual modes of thinking associated with word-based knowledge. Real paintings, by contrast, are meant to be experienced in three-dimensional environments within which we physically move around, and where we are open to more embodied, sensual forms of experience and knowledge.

Follow this link to order the book on Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Modern-Painting-Concise-History-World/dp/0500204896

Authority v Liberty. The curious case of South Korea

What kind of cosset do you want?

In my last post, I mentioned the censorship I have experienced in relation to the Chinese translation of my book, Seven Keys to Modern Art. Last week, in my class here in Korea with mainland Chinese students I brought it up with as much subtlety as possible. In the class, I discussed sociological approaches to modern art. As I am using Seven Keys as a textbook, and between them the ten Chinese and one Korean students have the Korean, English, and Chinese versions, they could compare editions. I pointed out the gap in the Chinese version between Barbara Kruger and Bill Viola, which is where Xu Bing should be. He’s gone because in my discussion in the book I refer to his shocked response to the repression in Tiananmen Square, which is still very much taboo in mainland China.

The students seemed very surprised. But also understandably rather tight-lipped about the omission.

I taught them the word ‘censorship’.

*

In the same class I showed the diagram above. It’s a rather good way of tracking the difference between China and the West, but also the unique position of the Republic of Korea. The West lies at the bottom right: ‘Individual Liberty’. China is up at the top right: ‘Collective Authority’. Hence the censorship. South Korea is somewhere in between. It’s an experiment in ‘Collective Authority plus Individual Liberty’.

The way in which these societies dealt with Covid helps to illustrate the differences. With its ‘zero tolerance’ attitude, China applied from the start its ‘Collective Authority’ model to the crisis. The West, by contrast, adopted an ‘Individual Liberty’ approach. South Korea dealt with Covid by mixing the two.

At first, ‘Collective Authority’ seemed the best option for everyone. The East Asian countries, being more attuned to this model, were quick to respond by introducing the necessary measures. China went to lockdown. The Western nations panicked, because ‘Individual Liberty’ is so obviously inappropriate in such a crisis, and they too went for lockdowns as an extreme recourse. South Korea managed to avoid lockdown, by contrast, but also any extreme spread of the virus. This is because with its unusual blend of ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ it was able to steer a middle course, epitomised by the skilful tracking of cases and the strict implementation of individual quarantines.

But with the evolution of the virus into the Omicron variant, ‘Individual Liberty’ has proven, rather surprisingly, in the long run a more robust social structure for dealing with the pandemic. China is now castrating itself by still pursuing the impossible goal of zero covid, even imposing lockdown once again in Wuhan, where the whole thing started. Only a society founded on ‘Collective Authority’ could work this way, that is, could be so rigid and maladaptive. Meanwhile, South Korea has segued to a situation in which the pandemic is confidently under control but in which people are still wearing facemask, because of the ‘Collective Authority’ component of this society. But it seems to me that the West has careened too fast away from the disagreeable experience of imposed ‘Collective Authority’ back towards a dangerous level of maskless ‘Individual Liberty’.

In this context, the tragic events in Itaewon, Seoul, over this Halloween weekend can be interpreted as an unfortunate unintended consequence of South Korea unique social blend, or social experiment. Inevitably, ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ exist in uneasy tension. South Koreans tolerate a – to Westerners - very high level of group control, but they are also primed by Western ideals of ‘Individual Liberty’. The result in this particular case was a massive feeling of release amongst the young after the restrictions imposed during the pandemic. But, ironically, their desire for individual liberty expressed itself in a very collective fashion!

Image source: http://factmyth.com/understanding-collectivism-and-individualism/