Blue jeans are still subversive (if you live in North Korea)!

More zany news from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Blue jeans are still subversive! Recent evidence of this is the censoring of a British television series about gardening that’s been pirated by the North Koreans to show on state television.

More zany news from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Blue jeans are still subversive over there! Recent evidence of this is the censoring of a British television series about gardening that’s been pirated by the North Koreans to show on state television. The host of ‘Garden Secrets’ is Alan Titchmarsh, who is something of a household name in the UK, and definitely harmless in every way. But when he’s seen wearing jeans, the DPRK censors do that bizarre digital blurring-out effect. This is what it looks like:

For a while a few weeks ago, the BBC had fun reporting the absurdity of this procedure. As the news item put it: “Jeans are seen as a symbol of western imperialism in the secretive state and as such are banned.” Alan Titchmarsh was on record as saying: "It's taken me to reach the age of 74 to be regarded in the same sort of breath as Elvis Presley, Tom Jones, Rod Stewart. You know, wearing trousers that are generally considered by those of us of a sensitive disposition to be rather too tight".

The subliminal message behind the story is clear: those North Koreans are definitely deranged and we (the Brits) are not. In fact, one of the perennial cultural roles of ‘exotic’ places located beyond the British Isles, especially those very far beyond, is to serve as sources of amusement and self-satisfaction for us Brits. The underlying message is usually that the only people with any common sense are us. Elsewhere, people are want to believe in the most silly nonsense, and to behave in ways that are perverse, indecent, childish, dangerous, etc. etc. In this way, the British status quo gets normalized as what’s ‘normal.’ As the public announcement says these days on the UK’s public transport system: ‘If you see something that doesn’t look right, call xxxxxx. See it. Say it. Sorted.’ Evidently, we are all supposed to automatically and unequivocally know what looks ‘right’ is. But how? Because we are habituated to a certain way of thinking and doing things. And for that to be possible, we need to be reminded regularly of the extra-ordinary. Which is where foreigners come in handy.

*

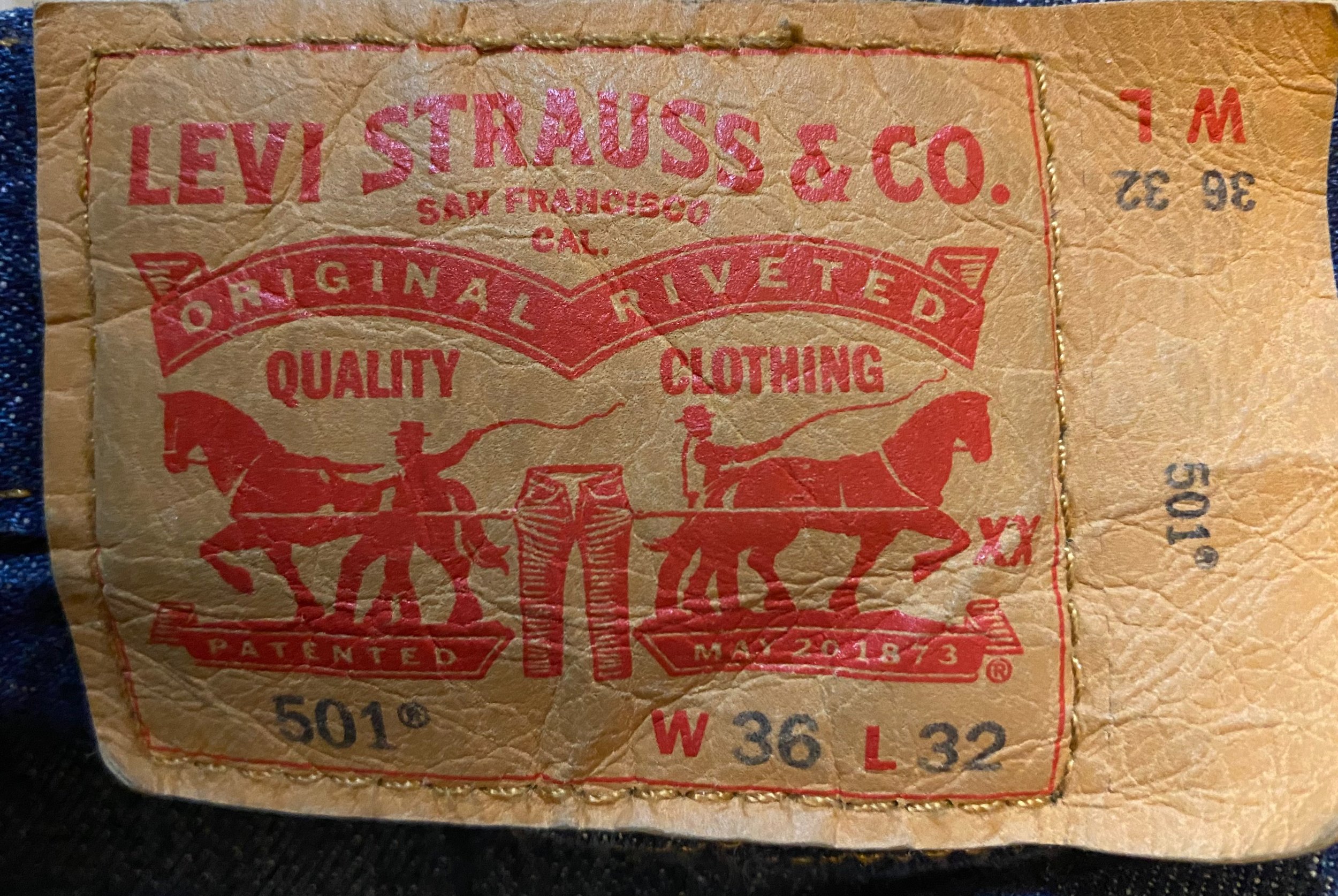

As you almost certainly know, denim jeans were designed in the second half of the nineteenth century in the United States as work wear. The inventor is usually credited as the German immigrant Levi Strauss, who moved to San Francisco during the ‘gold rush’ and patented the innovative design feature of riveted denim in 1873.

By the time I was ready to wear jeans in the late 1960s there were basically three brands on offer: Levis, Wrangler, and Lee, which were all American. As I became fashion conscious in my late teens in the mid-seventies, I decided for some reason (maybe it was something to do with Jack Kerouac and the Beats) that I could only wear Levi 501’s, the original, button fly, shrink-to-fit design (zippers were a standard feature by the mid-1950s). But there was nowhere in my hometown that sold these classic jeans, and so I would make a pilgrimage to nearby Brighton, where there was one shop that reliably stocked them. Once back home, I’d put the cherished (and rather expensive) item on, then lie in the bath watching the indigo dye turn the water blue as the jeans molded themselves nicely to the form of my lower torso and legs (or that was the goal, anyway).

And as they did, it was as if by an act of magical anointing I became part of the great success story. I became part of the American Dream. For while jeans are certainly cheap, comfortable, and hard-wearing, much more was being worn by my younger self than just blue cotton denim. By this time, jeans were a very powerful cultural signifier. What had started out in the west and mid-west of America as hardy workwear for cowboys, lumberjacks, farmers, and construction workers, by mid-twentieth century had morphed into a style icon sought by the young throughout the ‘free’ world. Like Coca-Cola, hamburgers and hotdogs, pop music, and rebellious and sexy youth, jeans came to represent a freer, happier way of life based on the American Dream.

First of all, American GI’s on service overseas – in Germany and during the Korean War and the Vietnam War in the East – wore them on leave, and they became a potent symbol of the new causal look of the Pax Americana. But at the same time, 1950s movies starring Marlon Brando and James Dean made jeans look attractively rebellious, and on Marilyn Monroe they looked sexy. So, jeans became increasingly a symbol of youth rebellion and anti-establishment attitudes. Many US schools in this period banned jeans from being worn by students. By the sixities jeans were what pop stars wore, and anti-Vietnam War protesters, and they were established as one of the most recognizable signifiers of non-conformity, if not of outright depravity. When I put on my blue Levi 501’s, aged sixteen in the provincial England of the mid-1970s, I was unconsciously identifying with the dominant version of ‘success’ within my society.

By the late 1980s you could buy ridiculously expensive ‘designer jeans’. This demonstrates how a symbol of rebellion gets easily co-opted or recuperated by what erstwhile rebellious young people even today (the West, anyway) call ‘the System.’ Jeans where you and I come from are definitely not any danger to civic order. Who knows what brand Alan Titchmarsh was wearing when he shot his gardening series. I bet they weren’t Levi 501’s. Then again, maybe they were…

My mum didn’t like blues jeans, either. I mean, back in the sixities and early seventies she didn’t like me to wear them. We lived in a suburb of a small seaside town, and she insisted I didn’t wear jeans when venturing into the centre of town. But eventually she bowed to the heady winds of cultural change that blew through the early 1970s and gave up on the dress restrictions. I never ever, ever thought I’d be able to draw a straight line between my mum’s sartorial code from back then and those of the DPRK today. But this yet more tragic proof that the DPRK is trapped in a time warp. Its animus against blue jeans belongs to the cultural values of the 1950s, not the present day. It quite simply hasn’t been able to progress beyond an ideological construct from the beginning of the Cold War.

But the DPRK is not alone. What the others so-called ‘rogue’ nations - Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan - have in common with the DPRK is precisely the refusal to westernize, to fail to swim with the seemingly inexorable tide of neoliberal global culturalism. To fall for the ‘American Dream” which has been exported to the ‘free’ world.

It’s worth spending a little time to consider just what this ‘dream’ is (or was). One on-line dictionary says it is “the ideal by which equality of opportunity is available to any American, allowing the highest aspirations and goals to be achieved.” But that seems a bit evasive. The website ‘Investopedia’ cuts to the economic chase: “The American Dream is the belief that anyone can attain their own version of success in a society where upward mobility is possible for everyone.”

But that’s narrowing things too much. From an artistic perspective, the American Dream means success equated with reward for the pursuit of extreme freedom of self-expression, willingness to shock and offend, and to push creativity continuously towards the ‘new’. In fact, these radical values were already part of the modern ‘Western European Dream’, but they were embraced and enhanced when they migrated to the ‘New World’, along with the useful additional assets of economic, military, and political power. Which makes one wonder: just what is ‘success’?

A more critical perspective is need. How about one applying a Marxist interpretation? Here’s something I found on the Internet: “When viewed through the lens of Marxism, the ‘American Dream’ is now more accurately described as a widespread fallacy than a meaningful goal to strive toward.” This quote comes from a very interesting source: a text written in 2023 by a pair of Iraqi academics in the course of writing a critique of Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’ (1949). This play is generally recognized as a searing indictment of the narrowly materialistic version of the ‘you-can-make-it’ ethos of the ‘American Dream’. (Just in passing, recall that, improbably, this same Arthur Miller was married to Marilyn Monroe, which means he could admire her figure in denim jeans at his leisure) The Iraqi academics, Ali Khalaf Othman and Fuad Sahu Khalaf, conclude:

What Willy (Loman, the eponymous ‘salesman’ who commits suicide) seemed to forget or really, judging from his actions, lacked even knowing, and I would go as far as saying, most of the world lack in knowing this next information, is that meritocracy, which is the system that is advertised in America, the system that is so alluring it makes America the land of dreams for refugees, because as long as you work hard enough, you can do anything, right? Well, no, not really. Willy found out the hard way, his family found out the hard way, and I hope, actual people can learn from this play and know before they find out the truth behind the American dream, the hard way.

These authors know what they’re talking about. Iraq is definitely a nation that was offered the ‘American Dream’. In fact it was forced upon them down the barrel of a M14. Disaster followed. Afghanistan is another tragic failure of this ‘dream’. Iran stand as the pioneer of such refusal, when in 1978 it had its Islamic revolution. What’s happening in Gaza and in Ukraine are also in their very different ways versions of the same refusal..

I’m wearing Levi 503’s as I write this post. I’ve given up on the original button-fly model, but the 503’s still have the same classic cut but with a zipper fly (much easier to handle as you get older). I purchased my pair (and lots of other Levi’s clothes, as I have become a walking (and somewhat aged) advertisement for this American icon) at the Levi’s store in the Lotte Outlet in Paju Book City, near where we live. It’s just a stone’s throw from the DMZ. I can imagine a North Korean border guard averting his eyes regularly, as across the narrow Han estuary he glimpses through high-powered binoculars South Koreans of all ages passing lewdly by in denim jeans (including Levi’s, but also, no doubt, ones by Armani).

I’m in absolutely in no doubt where I’d rather be living: somewhere I can were jeans whenever and whenever I like.

And to end, here’s the label from my current pair of Levi 501’s. Subversive stuff, indeed!

NOTES

The photograph at the top of the post is a screen grab from the BBC News website: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-68664644

The dictionary definition is from: https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/

Investopedia quote is from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/american-dream.asp

The essay on ‘Death of a Salesman’ can be found at: https://www.iasj.net/iasj/download/29d6c8a71ed03d4b

Authority v Liberty. The curious case of South Korea

What kind of cosset do you want?

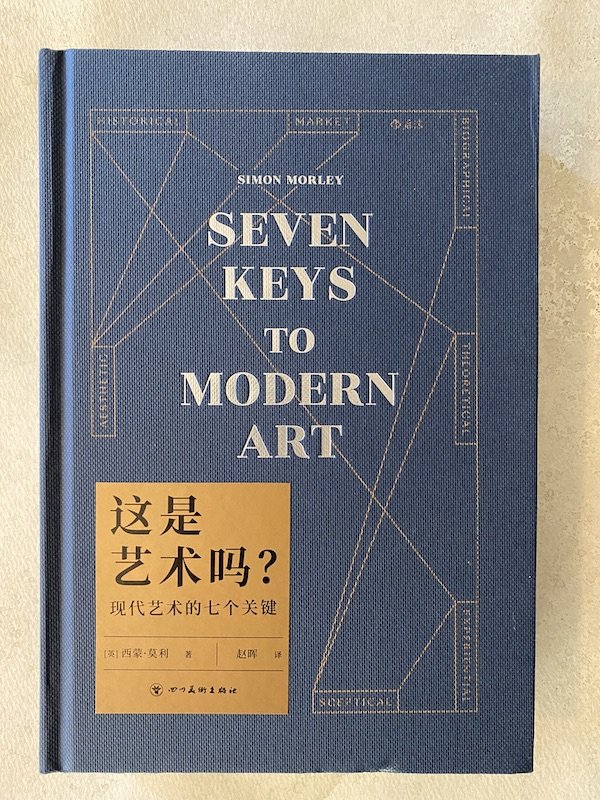

In my last post, I mentioned the censorship I have experienced in relation to the Chinese translation of my book, Seven Keys to Modern Art. Last week, in my class here in Korea with mainland Chinese students I brought it up with as much subtlety as possible. In the class, I discussed sociological approaches to modern art. As I am using Seven Keys as a textbook, and between them the ten Chinese and one Korean students have the Korean, English, and Chinese versions, they could compare editions. I pointed out the gap in the Chinese version between Barbara Kruger and Bill Viola, which is where Xu Bing should be. He’s gone because in my discussion in the book I refer to his shocked response to the repression in Tiananmen Square, which is still very much taboo in mainland China.

The students seemed very surprised. But also understandably rather tight-lipped about the omission.

I taught them the word ‘censorship’.

*

In the same class I showed the diagram above. It’s a rather good way of tracking the difference between China and the West, but also the unique position of the Republic of Korea. The West lies at the bottom right: ‘Individual Liberty’. China is up at the top right: ‘Collective Authority’. Hence the censorship. South Korea is somewhere in between. It’s an experiment in ‘Collective Authority plus Individual Liberty’.

The way in which these societies dealt with Covid helps to illustrate the differences. With its ‘zero tolerance’ attitude, China applied from the start its ‘Collective Authority’ model to the crisis. The West, by contrast, adopted an ‘Individual Liberty’ approach. South Korea dealt with Covid by mixing the two.

At first, ‘Collective Authority’ seemed the best option for everyone. The East Asian countries, being more attuned to this model, were quick to respond by introducing the necessary measures. China went to lockdown. The Western nations panicked, because ‘Individual Liberty’ is so obviously inappropriate in such a crisis, and they too went for lockdowns as an extreme recourse. South Korea managed to avoid lockdown, by contrast, but also any extreme spread of the virus. This is because with its unusual blend of ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ it was able to steer a middle course, epitomised by the skilful tracking of cases and the strict implementation of individual quarantines.

But with the evolution of the virus into the Omicron variant, ‘Individual Liberty’ has proven, rather surprisingly, in the long run a more robust social structure for dealing with the pandemic. China is now castrating itself by still pursuing the impossible goal of zero covid, even imposing lockdown once again in Wuhan, where the whole thing started. Only a society founded on ‘Collective Authority’ could work this way, that is, could be so rigid and maladaptive. Meanwhile, South Korea has segued to a situation in which the pandemic is confidently under control but in which people are still wearing facemask, because of the ‘Collective Authority’ component of this society. But it seems to me that the West has careened too fast away from the disagreeable experience of imposed ‘Collective Authority’ back towards a dangerous level of maskless ‘Individual Liberty’.

In this context, the tragic events in Itaewon, Seoul, over this Halloween weekend can be interpreted as an unfortunate unintended consequence of South Korea unique social blend, or social experiment. Inevitably, ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ exist in uneasy tension. South Koreans tolerate a – to Westerners - very high level of group control, but they are also primed by Western ideals of ‘Individual Liberty’. The result in this particular case was a massive feeling of release amongst the young after the restrictions imposed during the pandemic. But, ironically, their desire for individual liberty expressed itself in a very collective fashion!

Image source: http://factmyth.com/understanding-collectivism-and-individualism/

What’s going on in China?

My experience of being censored by the Chinese!

China’s been in the news because of the 20th Party Conference in Beijing at which Premier Xi Jinping guaranteed himself a third term in office. Like me, you must have been confused by the footage of the previous Premier, Hu Jintao being escorted rather forcibly away:

What’s going on? It reminded me of a similar moment in North Korea in 2013 when Jang Song-thaek was similarly very publicly removed from a meeting of the WPK Political Bureau:

Later it was announced that Jang had been executed. Will the same thing happen to Hu? Probably not. The Chinese Communist Party is more subtle. He’ll simply disappear from public view.

This is the way they do it in dictatorships, apparently! It’s important to show who’s boss.

As I noted in a previous post, the philosopher Karl Popper wisely observed that the benefit of democracy is not so much that people get to vote but that leaders get to be removed from power without risk of violence. The contrast to the UK at the moment is striking. We are certainly way more genuinely democratic in this sense than China and North Korea, and our leaders very evidently get removed from power. But our democracy is still obviously very flawed as we are obliged to watch charlatans taking it in turns to become Prime Minister in a risible game of musical chairs.

***

China is especially on my mind because a couple of my books are now in Chinese translations. Seven Keys to Modern Art, and The Simple Truth. The Monochrome in Modern Art. Here they are:

The mainland Chinese version.

The Taiwan Chinese version.

The Taiwan Chinese version of The Simple Truth.

Seven Keys was published by Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House in Beijing, while Seven Keys and The Simple Truth was published by Diancan Art and Collection Ltd. in Taipei, Taiwan. But I have only received copies (and recently) of the mainland Chinese version of Seven Keys, and can find almost nothing about the Taipei edition on English language Google. The Taipei publisher did a couple of weeks ago send me three copies of the recently published Chinese translation of The Simple Truth. But still no sign of their Seven Keys.

The fact that Seven Keys has been published in Chinese in both Taiwan and mainland China may seem a bit odd, and also surprising, because the English edition, published by Thames & Hudson, couldn’t be printed in China because one of the artists I discuss is Xu Bing, whose work is related to the Tienanmen Square protests in 1989. This is a taboo subject in the People’s Republic! So, I assumed at first that Party censorship has become relaxed enough to allow the unexpurgated publication of my book. But of course not! When I looked at the mainland Chinese version more closely I realize that there is now no chapter on Xu Bing!

This is ironic for me, because I am currently teaching (in English) a PHD class here in Korea made up of almost entirely of mainland Chinese students - about ten of them - plus one solitary Korean. I am using Seven Keys as a text book, so the students can choose between using English, two Chinese, or Korean translations. But I hadn't realized until very recently that the mainland Chinese version, which is the one for sale on Amazon (no sign there of the Taiwan version…) and the one several of the Chinese students have opted to purchase, that Xu Bing has been excised.

Image Sources:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/23/xi-jinping-chooses-yes-men-over-economic-growth-politburo-purge-china

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/23/xi-follows-maos-footsteps-puts-himself-at-core-of-chinas-government

https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_northkorea/614727.html