A small ray of North Korean hope

Some photographs presented on the BBC’s news website documenting the recent mass spectacle in Pyongyang have compelled me anew to comment on the utter madness of the North Korean state, which, I hasten to add, begins just a few miles north of where I write these words.

I suppose living so close to possibly the most dysfunctionally functional state in the world is a sobering experience. Basically, it helps me remember that humanity is far weirder than I can imagine.

One picture especially caught my eye. The picture above. And now look at this detail::

I wonder if this is an ‘emperor’s new clothes’ picture. Note the little girl staring at the camera. What is she thinking? is it too much to hope that she is seeing through the madness of the adults? Probably. After all, the system starts the process of mind control very early. But even so. This seems unscripted. I couldn’t help feeling that the little girl is shattering the surface of the collective delusion. And does that mean that the photographer is colluding? Even though this is an official picture aimed at consolidating the official narrative, can we see here a subtly resistant action? Doubtful. Because that would be much too dangerous. But nevertheless……

I was also given adequate evidence that the BBC and the system it serves, and within which I live, is also pretty damn nutty. Look at this:

A stupid advertisement lodged between stupid images. Perhaps we are just as mad in our way as these North Koreans…….

The First Pictures of Roses. Part II

This is the oldest pictorial evidence of humanity’s love of roses. A fragment of fresco dating to the Bronze Age, painted by an artist working within the Minoan civilization in Crete (2000-1500BCE). It was discovered by the British archeologist Sir Arthur Evans, who began his excavations at Knossos in 1899. In this photo, you can see the roses top and bottom left.

Fresco technique involves the painting of colour pigments without a binding agent on still wet lime plaster, so that the paint is absorbed into the plaster and thereby fixed and protected from fading. The darker parts in the picture are hypothetical restorations not the original fresco, which can be made out in the more weathered and rough areas of the image. Due to the overzealous and botanically ignorant restorers hired by Evans, some of the extant images of roses got turned into six petalled flowers and were re-coloured yellowish pink. As a result, they have been variously named as Rosa persica, (which is a yellow rose),Rosa ricardii, or Rosa canina.

Fortunately, towards the lower left-hand side the restorers left one area unmodified, and in a faded area of the design we can name out the vague form of a rose with five overlapping petals in pale pink, which has been more convincingly named a Rosa pulverulenta, a wild rose that is still growing in western and central Crete.

Here is a detail:

And here is Rosa pulverulenta:

As you can see, this rose is indeed quite similar to Rosa canina, the Dog Rose:

Just what the Minoans thought of the rose we will never know. But during the Bronze Age in the Fertile Triangle (which today includes Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, the northeast and Nile valley regions of Egypt, the southeastern region of Turkey, and the western part of Iran), relatively complex societies developed which prospered through the use of advanced irrigation agriculture, and where there evolved a culture of flowers. Along with the domestication of cereal plants and animals, it seems roses were also cultivated, perhaps for the medicinal properties of the hips, to serve as hedges (the thorns kept out animals), or maybe just because they looked beautiful. The interest in domesticating the rose then spread westwards deeper into the Mediterranean region to encompass the Minoan civilization and the Mycenaeans of the Greek mainland. But along with practical and aesthetic uses, the symbolic value of the rose also spread. This will be the subject of my next post.

By Any Other Name. A Cultural History of the Rose. Published soon!

As I mentioned in a post a while ago, my new book is called By Any Other Name. A Cultural History of the Rose. It will published in October by Oneworld!

This is from the promotional blurb:

The rose is bursting with meaning: over the centuries it has come to represent love and sensuality, deceit, death and the mystical unknown. Today the rose enjoys unrivalled popularity across the globe, ever present at life's seminal moments.

Grown in the Middle East two thousand years ago for its pleasing scent and medicinal properties, it has attached itself to us, its needy host and servant, to become one of the most adored flowers across cultures. The rose is well-versed at enchanting human hearts – no longer selected by nature, but by us. From Shakespeare's sonnets to Bulgaria's Rose Valley to the thriving rose trade in Africa and the Far East, via museums, high fashion, Victorian England and Belle Epoque France, we meet an astonishing array of species and hybrids of remarkably different provenance.

This is the story of a hardy, thorny flower and how, by beauty and charm, it came to seduce the worl

Take a look at my previous posts on roses, and in my posts over the next couple of months I will focus on the book and its subject, writing about some of the contents of the book, mostly my favourite stories about the rose.

For today, I would like to mention the endpapers, which are designed by my partner, Chang Eungbok. Here is a picture:

Eungbok used images from P.J. Redouté’s famous book Le Roses. Known as the “Raphael of flowers’, Redouté’s botanical paintings remain to this day unsurpassed. They combine botanically accuracy and high aesthetic value. Redouté was master draughtsman to the court of Marie-Antoinette before the French Revolution, and seems to have been of a harmlessly apolitical disposition, because he soon found himself similarly employed by Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife, Empress Joséphine, whose love of roses, was largely responsible for launching the nineteenth century’s vogue for growing roses. After Napoleon’s defeat and the Restoration in 1815, Redouté found gainful employ again with the crème de la creme, which was now Marie-Amelie de Bourbon, the queen of King Louis-Philippe. Between 1817 and 1824, using mostly the roses in the gardens of Joséphine’s former Château at Malmaison as his models, Redouté embarked on Les Roses, which was eventually published in 30 fascicles of usually six plates, each with a commentary by the naturalist Claude-Antoine Thory. Regrettably, the originals were destroyed in a fire in the Library of the Louvre in 1837, but numerous printed first editions have survived.

Your an see lots of Chang Eungbok’s work on her website: www.monocollection.com

From ‘developing’ to ‘developed’

Development, South Korean style.

Recently (July 2nd), the Republic of Korea was elevated from the status of ‘developing’ to ‘developed’ nation by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which reclassified it from Group A (Asian and African countries) to Group B (developed economies). This is quite an upgrade. It’s the first since the agency’s formation in 1964. As the website KOREA.net explains: ‘UNCTAD is an intergovernmental agency with the purpose of industrializing developing economies and boosting their participation in international trade. Group A of the organization comprises mostly developing economies in Asia and Africa; Group B developed economies; Group C Latin American and Caribbean States; and Group D Russia and Eastern European nations.’

The South Koreans are understandably very proud of themselves. This is an unparalleled achievement. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953 the Republic’s gross domestic product - the total value of goods produced and services provided in a country during one year - has leapt 31,000 fold! One could say that the concept of ‘development’ is the nation’s mantra, which is enshrined in the commonly used phrase ‘dynamic Korea’.

So what does development look like on the ground, so to speak? Everywhere you go in South Korea (except the remote mountainous regions) you see construction work going on – for massive elevated superhighways and high-speed rail links, or whole new cities comprised of clusters of giant apartment towers. Even here where I live, near the DMZ, where, because of proximity to the frontier, infrastructural, commercial and residential transformations are restricted, some kind of building work is constantly going on. For example, recently a construction company began slicing into a wooded hillside near us, first uprooting the silver birch trees growing there and then carting away tons of soil in convoys of heavy-load trucks (mostly made by Volvo, so it seems) in order to create a terraced slope upon which, apparently, they will be building hanok-style housing. Hanoks are the traditional one-storey wooden houses of Korea, almost none of which have survived from more than one hundred years ago, not just because of accidental fires or the destruction of warfare but because of the nation’s commitment to a specific model of development. For the past seventy years the hanok has symbolized the ‘undeveloped’. In fact, one could not imagine a greater contrast in housing than between a hanok and an apartment tower, between old-style Korean living accommodation and the contemporary. This alone indicates that for South Koreans development is also Westernization.

a traditional Korean hanok.

But wait. The UNCTAD is concerned only with development in terms of the economy and trade, but obviously the term has other resonances, that go well beyond the economic. So before we start hailing the South’s triumph, here is another recent statistic: The Korea Development Institute announced just two months before the UNCTAD elevated the country to ‘developed nation’ status that South Korea scored 5.85 on a scale of 1 to 10 for the period of 2018 to 2020 on the U.N. World Happiness Index. This score is the third-lowest in the OECD (the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development).

Oh dear. The South Koreans are economically ‘developed’ but not very joyful ,satisfied, content or fulfilled. But it might seem disingenuous of me to mention failure when the Republic of Korea has clearly achieved so much for its citizens, most especially when compared to what the North Korean leadership has done for its people. In 2019 South Korea’s GDP was 2 percent while North Korea’s was 0.4 percent, and the gap has widened even more since then thanks to sanctions and the pandemic. But I wonder what North Koreans would say if they were canvased about happiness. But of course, the rulers of North Korea would never allow any such survey to be made, and if they did it themselves the answer is a forgone conclusion, and anyone stupid enough to report that they were unhappy would almost certainly be bundled off to a labour camp, or worse. But if such a survey did take place, done by external assessors, I suspect the North Koreans would still turn out to be at the very top of the happiness league. Why? Firstly, because of the indoctrination I discussed in my last blog entry. In fact, if you think about it, the entire North Korean propaganda machine is directed towards fabricating an aura of universal (I mean within North Korea) happiness. Take a look at these two North Korean posters. The text in the first translates as ‘Wear traditional Korean clothing, beautiful and gracious’, the second; “Working on Friday is patriotic’ (1):

The worrying thought is that the North Koreans really are ‘happy’, in the sense that the word is forced to have within the ruling ideology. But there is another reason. The Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen notes that people can internalize the deprivations of their circumstances so they don’t desire what they never expect to have. Such an ‘adaptive preference’ would be another way of understanding a North Korean person’s subjective judgment concerning their well-being, and explains how it would be very different from a neutral observer’s perceptions.

But this is also an indication that we should in general be cautious about using subjective opinions of well-being as valid criteria for assessing happiness. Because just what is it? The indicators used for gauging national happiness levels in the UN World Happiness Index are these: GDP per capita, household income, healthy life expectancy, social support, generosity (in the sense of willingness to donate), institutional trust, corruption perception, positive affect/negative affect, freedom to make life choices. These criteria are partly based on the tiny but very wealthy (thanks to oil reserves) nation of Bhutan, which pioneered its own Gross Happiness Index which subsequently become another transcultural indicator. It highlights the following: health, education, use of time, psychological well-being, good governance, cultural diversity and resilience, ecological diversity and resilience, community vitality, and living standards.

Obviously, as the disjunction between South Korea’s development status and happiness status shows, development cannot be reduced to mere economic terms. The trouble is that all to readily it is, and this is because development is the key driving concept behind modernization, and is closely linked to another key concept: ‘progress’. This is what the philosopher John Gray says in Enlightenment’s Wake (1995): ‘The idea of progress….is the modern conception of human social development as occurring in successive discrete stages, not everywhere the same, but having in common the property of converging on a single form of life, a universal civilization, rational and cosmopolitan.’ Gray is a prominent critic from within the West (he is British) of what he sees as the calamitous consequences of this universalizing ‘Enlightenment project’, which has been foisted on the rest of the world by the West. Gray writes: ‘My starting-point is the failures of the Enlightenment project in our time, and their implications for liberal thought. The failures to which I refer are in part historical and political rather than theoretical or philosophical: I mean the confounding of Enlightenment expectations of the evanescence of particularistic allegiances, national and religious, and of the progressive levelling down, or marginalization, of cultural difference in human affairs.

A fundamental error of the ‘Enlightenment project’ was to assume that the progress it celebrated would be limitless, and also to link it excessively to economic growth. Now we know that this could be a fatal error for which the generations to come will pay the price. Development must be sustainable and based on much more than purely upward economic growth. Sen offers one way forward in his Capability Approach to development, which stresses the relationship between development and ethics by focusing on the individual’s capability for achieving the kind of life they have reason to value. This is different from thinking in terms of subjective well-being or having access to the means for pursuing the good life. As the Encyclopaedia of Philosophy puts it, in Sen’s theory, ‘[a] person’s capability to live a good life is defined in terms of the set of valuable ‘beings and doings’ like being in good health or having loving relationships with others to which they have real access.’ In other words, the idea is to place development within a tangible and specific context based on the pre-eminence of sustainability. It thereby counters the slash-and-burn development concept behind the ‘Enlightenment projects ideal of progress.

North Korea hitched itself up to an especially disastrous legacy of this Enlightenment project - communism. It got shipwrecked precisely due to the forces of Gray indicates. In fact, one could argue that North Korea is an exemplary example of ‘particularistic allegiances’. It is also the mirror image of South Korea’s version of development., and one could fruitfully analyze the two Koreas in terms of how they chose antithetical criteria for defining the idea of development. For example, while the South adopted an essentially economic model of development founded on global commerce, which was borrowed from Western capitalism, the North chose first the communist alternative, and then what it calls ‘juche’, the ideal of self-reliance, in the sense of development understood as autonomy and independence. Development for the North Korean state is therefore defined as remaining separate and distinct from the rest of the world, and on being dependent solely on its own strength under the guidance of a godlike leader. But I wonder how many more South Korean hillsides will be carted away in trucks to construct more housing as part of the relentless drive to develop? I imagine a speeded-up movie of South Korean’s development over the past seventy years would look like an earthquake of truly terrible proportions.

(1) For more North Korean posters see: https://library.ucsd.edu/news-events/north-korean-poster-collection/

Brainwashed!

North Korean schoolchildren.

According to Google’s English dictionary, the term ‘brainwashing’ means ‘the process of pressuring someone into adopting radically different beliefs by using systematic and often forcible means.’ It dates from the early days of Chinese communism and the period of the Korean War (1950-53). On March 11, 1951 the New York Times reported: ‘In totalitarian countries the term “brainwashing” has been coined to describe what happens when resistance fighters are transformed into meek collaborators.’ But the word gained popular currency largely as a result of the experience of American Prisoners of War held by the Chinese during the Korean War, and in a previous post I mentioned the theory of ‘totalism’ developed by the American psychologist Robert Jay Lifton, a consequence of interviewing former American PoWs who experienced Chinese ‘re-education’ practices. But Lifton used the more neutral-sounding term ‘thought reform’ rather than ‘brainwashing.’

I recently came across this document, which is available on-line: a report commissioned in 1955 by the US Office of the Secretary of Defence, POW. The Fight Continues After the Battle. It directly addressed the experience of GI’s taken prisoner. On the topic of brainwashing or ‘thaught reform’ it stated:

When plunged into a Communist indoctrination mill, the average American POW was under a serious handicap. Enemy political officers forced him to read Marxian literature. He was compelled to participate in debates. He had to tell what he knew about American politics and American history. And many times the Chinese or Korean instructors knew more about these subjects than he did. This brainstorming caught many American prisoners off guard. To most of them it came as a complete surprise and they were unprepared. Lectures, study groups, discussion groups, a blizzard of propaganda and hurricanes of violent oratory were all a part of the enemy technique.

A large number of American POWs did not know what the Communist program was all about. Some were confused by it. Self-seekers accepted it as an easy out. A few may have believed the business. They signed peace petitions and peddled Communist literature. It was not an inspiring spectacle. It set loyal groups against cooperative groups and broke up camp organization and discipline. It made fools of some men and tools of others. And it provided the enemy with stooges for propaganda shows.

Ignorance lay behind much of this trouble. A great many servicemen were teen-agers. At home they had thought of politics as dry editorials or uninteresting speeches, dull as ditchwater.

But the report concluded:

The Committee made a thorough investigation of the "brain washing" question. In some cases this time consuming and coercive technique was used to obtain confessions. In these cases American prisoners of war were subjected to mental and physical torture, psychiatric pressures or "Pavlov Dogs" treatment.

Most of the prisoners, however, were not subjected to brain washing, but were given a high-powered indoctrination for propaganda purposes.

However, by this period the term ‘brainwashing’ was already being used in a more general sense to include such ‘high-powered indoctrination for propaganda purposes’, and the distinction the report makes is no longer so easy to sustain. Furthermore, the word was extended in the late 1950s to describe malign psychological influences in general, such as when consumers are duped through salesmanship and advertising into purchasing things they don’t need. This in its turn reflected the growing awareness of the power of the ‘hidden persuaders’ (the name of a bestselling book about advertising by Vance Packard, published in 1957) and the mass media to manipulate not just patterns of consumption but thoughts, attitudes, values and behaviour as a whole.

To bring the issue of brainwashing up to date, here is an extract from the memoir of the North Korean defector Yeonmi Park, In Order To Live: A North Korean Girl’s Journey to Freedom (2016), which I mentioned in previous blog, where she talks about her experience at school in North Korea:

In the classroom every subject we learned — math, science, reading, music — was delivered with a dose of propaganda.

Our Dear Leader Kim Jong Il had mystical powers. His biography said he could control the weather with his thoughts, and that he wrote fifteen hundred books during his three years at Kim Il Sung University. Even when he was a child he was an amazing tactician, and when he played military games, his team always won because he came up with brilliant new strategies every time. That story inspired my classmates in Hyesan to play military games, too. But nobody ever wanted to be on the American imperialist team, because they would always have to lose the battle.

………

In school, we sang a song about Kim Jong Il and how he worked so hard to give our laborers on-the-spot instruction as he traveled around the country, sleeping in his car and eating only small meals of rice balls. “Please, please, Dear Leader, take a good rest for us!” we sang through our tears. “We are all crying for you.”

This worship of the Kims was reinforced in documentaries, movies, and shows broadcast by the single, state-run television station. Whenever the Leaders’ smiling pictures appeared on the screen, stirring sentimental music would build in the background. It made me so emotional every time. North Koreans are raised to venerate our fathers and our elders; it’s part of the culture we inherited from Confucianism. And so in our collective minds, Kim Il Sung was our beloved grandfather and Kim Jong Il was our father.

Once I even dreamed about Kim Jong Il. He was smiling and hugging me and giving me candy. I woke up so happy, and for a long time the memory of that dream was the biggest joy in my life.

Jang Jin Sung, a famous North Korea defector and former poet laureate who worked in North Korea’s propaganda bureau, calls this phenomenon “emotional dictatorship.” In North Korea, it’s not enough for the government to control where you go, what you learn, where you work, and what you say. They need to control you through your emotions, making you a slave to the state by destroying your individuality, and your ability to react to situations based on your own experience of the world.

This dictatorship, both emotional and physical, is reinforced in every aspect of your life. In fact, the indoctrination starts as soon as you learn to talk and are taken on your mother’s back to the inminban meetings everybody in North Korea has to attend at least once a week. You learn that your friends are your “comrades” and that is how you address one another. You are taught to think with one mind.

………

In second grade we were taught simple math, but not the way it is taught in other countries. In North Korea, even arithmetic is a propaganda tool. A typical problem would go like this: “If you kill one American bastard and your comrade kills two, how many dead American bastards do you have?”

But why do I mention ‘brainwashing’ now? Because in today’s The Korea Herald there was an article by J. Bradford Delong, a former deputy assistant US Treasury secretary, and now professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley entitled ‘The summer of disaster.’ The ‘disaster’ Delong has in mind is not ecological. He referred to the COVID-19 pandemic and the devastation wrought by the new delta variant, but above all he was referring to what might be called a ‘cognitive’ disaster: the impact of the brainwashing on large segments of the American population. Delong wrote:

The message being blared by Fox News and most other right-wing outlets goes something like this:

‘Superman-President Donald Trump quarterbacked the incredibly successful Operation warp Speed project, which performed biotech mircales and created a highly effective vaccin against a disease that is just like the flu. But now, the vaccines are untested and unsafe. We should never have worn masks.

The virus is a Chinese bio-weapon funded bt Dr. Fauci, who constantly gave Trump bas advice about this gigantic hoax. The medical establishment is suppressing information about truly useful medications like ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine and hydrogen peroxide.’

As Delong continues:

If this conspiratorial word salad sounds crazy, consider the terrifying fact that around one-quarter of the Americn population apparently believes it (or at least some part of it). One-fifth of Americans think that the US government is using COVID-19 vaccination to implant microchips into their bodies. Tens of millions of Americans have found sufficient reason to un a 1 percent risk of death by refusing an extremely effective, extremely safe, widely available vaccine.

Consider the implications of this successful act of brainwashing. A country where malevolent, cynical media and political operatives can trigger such deep psychological fractures in a significant share of the population us extremely vulnerable to a wide range of threats. What will Americans fall for next?

As the official report into PoWs from 1955 quoted from above noted, the main contributory factor here is also ‘ignorance’, a lack of education, of the capacity for critical thinking. But what Delong emphasises is the extent to which the powerful have a vested interest in keeping people ‘ignorant’, the better to manipulate them. The ‘high-powered indoctrination for propaganda purposes’ described by the 1955 report is very much in operation, and Delong specifically laments the role of the right-wing media.

Obviously, the extent of brainwashing in North Korea is far greater, and far more insidious and deadly, than anything going on in the United States. But Delong’s neat overview of the current cultural polarization there, when seen in juxtaposition with Yeonmi Park’s memoir, should give us pause for thought, and remind us that if we want to get to the roots of brainwashing, or whatever you want to call it, it is necessary to go back well before people become viewers of Fox News or reach voting age. In one way or another, the process of ‘high-powered indoctrination’ is in fact systemic in human society, in the sense that it pervades everyone’s life from the moment of birth, maybe even before, if one takes into account the impact of external influences on the unborn baby. North Korea reveals this to a terrible degree, as Yeonmi Park’s story attests, but we should also turn spotlight around and see what is happening closer to home.

We can see very blatantly the important role played by ‘ignorance’ in determining what people believe in the case of others – North Koreans, Republicans – and easily forget how ‘high-pressure indoctrination’ also goes on in our own lives. Now, I am by no means claiming there is some kind of parity between the trouble Yeonmi Park had at Columbia University - which I mentioned in previous posts - with what she experienced before her escape, although she was indeed led to ask whether she had simply freed herself from one form of especially cruel brainwashing in order to be exposed to another more insidious kind. Park’s confrontation with the ‘high-pressure indoctrination’ of of ‘political correctness’ or ‘wokeism’, or whatever you want to call it, of experiencing a different process that involved being pressured into ‘adopting radically different beliefs by using systematic and often forcible means’, led Park to ask a very basic and tragic question: can we ever be free from these malign pressures to conform? Of course, no one gets sent to a concentration camp for refusing to tow the politically correct line at Columbia. Maybe if they are a professor they will lose their teaching position. But we should surely be alert to the extent to which we are also brainwashed without being aware of it. We should acknowledge that when beliefs are conducive to our own mindset we tend to be blind to where these beliefs came from and what they are doing to us.

*

So, why are we all so susceptible to brainwashing?

Consider the fact that for those who have brought into the narratives described by Park and Delong that for them this is reality.

In The Ego-Tunnel. The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self (2009) the neurophilosopher Thomas Metzinger sums up what we now know about the human mind:

Modern neuroscience has demonstrated that the content of our conscious experience is not only an internal construct but also an extremely selective way of representing information. This is why it is a tunnel: What we see and hear, or what we feel and smell and taste, is only a small fraction of what actually exists out there. Our conscious model of reality is a low-dimensional projection of the inconceivably richer physical reality surrounding and sustaining us. Our sensory organs are limited: They evolved for reasons of survival, not for depicting the enormous wealth and richness of reality in all its unfathomable depth. Therefore, the on-going process of conscious experience is not so much an image of reality as a tunnel through reality.

This means that essentially we exist in a ‘world simulation created by our brains,’ as Metzinger puts it. What does this ‘world simulation’ aim at?Because our minds have a limited capacity to process information we attempt to adopt strategies that simplify complex problems, and we are forever trying to conserve cognitive energy. This extends to all kinds of situations involving cognitive engagement. The dominant need at any time becomes the foreground ‘figure’, and the other needs recede, at least temporarily, into the background. For example, a person may be thinking about a particular relationship, which is then ‘figure’, but as soon as the focus is shifted to thoughts about a job, the job becomes ‘figure’. Needs move in and out of the ‘figure - ground’ fields. After a need is met it recedes into the ‘ground’, and the most pressing need in the new gestalt then emerges from the ‘ground’ as a new ‘figure’. In this way a particular need emerges, is met, and then directs a person's behavior. Normal, lucid consciousness is pre-disposed to accept a ‘ready-made’ gestalt, and generally, familiar configurations win out over the novel because cognitive value is understood to lie in repeatability and reliability. A ‘horizon’ of meaning limits what we can see, and what we can think.

In simple terms, this process aims to minimize fear and maximize hope. The Republican mindset is based on the awareness that hope is fundamental to the meaningful life, and after their own fashion the fellow traveller has generated a ‘world simulation’ conducive to the expectation of a positive outcome. But obviously, hope can all too easily be founded on delusions, over-confidence, over-simplifications, errors of judgment, and moral, practical, personal and collective failure. A consoling narrative replaces the anxiety induced by random facts by the comfort of a coherent pattern, offering a solution to complex and intractable problems through flattening them into a clear narrative. The story requires only the most tenuous connection to actual facts in order to endure, and the hope it fosters is above all about assuaging anxiety and fear in the present, not about working towards credibly achievable goals in the future. The - to us - obviously delusional beliefs of many Republicans is ample evidence that hope does not need to be founded on a sound, reasoned assessment of the possibilities of a positive outcome. But they are an especially obvious and worrying indication that nowadays it is becoming extremely difficult to feel hopeful through rational appeal to the facts in the ways that the ‘reality-based’ community considers essential.

I mentioned ‘ignorance’ in relation to Republicans in a previous post, but perhaps a more apposite and neutral word to describe the dynamics of brainwashing is not so much ‘ignorance’ as ‘narrative.’ For those of us located outside the compelling aura of the stories described by Park and Delong it is easy to mock the naivety of the true believer. But aren’t we all in more or less in thrall to basically the same curious psychological deformation? Our mindset is usually based on a highly selective appraisal of available information, and on the very human capacity to overlook anything that risks challenging or contradicting the particular narrative of hope in which we have invested.

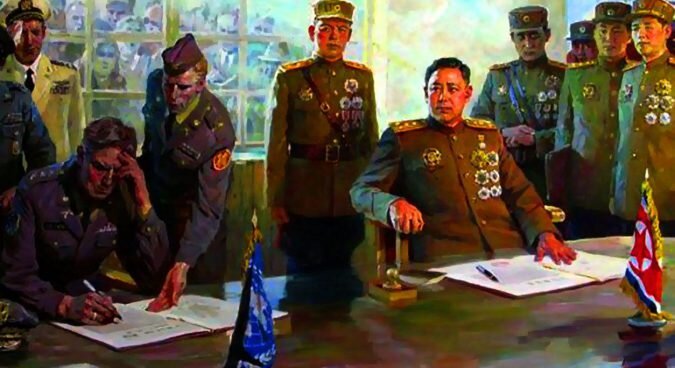

68th Anniversary of the end of the Korean War

The signing of the armistice to end hostilities in Korea, 27th July 1953.

The official North Korean version of the Armistice signing, as painted by a North Korean artist working in the mandatory ‘socialist realist’ style copied from the Soviet Union. Looks like victory, doesn’t it?

Today, 27th July, is the sixty-eighth anniversary of the end of the Korean War, which didn’t officially end at all. Only an armistice was signed sixty-eight years ago. So technically, the war is still going on, only in suspended animation. That’s definitely sometimes how it feels here, next to the DMZ. It’s as if both sides have been holding their breath ever since 1953, meanwhile building defenses and going about their other business. As is obvious, ‘business’ has on the whole been better for the Korea south of the DMZ than the one north of it.

The War lasted from 25th June 1950 to 27th July 1953. Less than two months after the North Korean invasion, their army controlled most of the Korean peninsula, and the Republic of Korea and US forces defended only a perimeter around the south-eastern port of Pusan. But in autumn 1950, the U.S.-led United Nations counteroffensive pushed back the North Korean army all the way up to near the Chinese border. It was at this point that the recently triumphant Chinese Communist party came to its neighbor’s aid by sending thousands of ‘volunteers’ to fight. The Chinese counteroffensive devastated the UN advance, and retook Seoul. After that, the War became a bloody stalemate lasting another two and a half years..

But the key player was Josef Stalin. Research in Soviet archives done during the brief period in the early 1990s when Yeltsin let scholars and journalist consult them, and before Putin slammed the door shut again, show conclusively that by early 1952 Stalin, who had green-lighted his protege, Kim Il Sung’s, invasion, had already decided the war couldn’t be won, but also that it couldn’t afford to be lost either. Peace had to be delayed in order to divert attention., and he deliberately made sure that the Armistice negotiations out for over more than two years, making the Chinese and North Koreans comply with his strategy. In fact, the North Koreans themselves didn’t seem to have much say in how the war was waged. Everything was decided by Stalin, and by Mao, after China joined the conflict.

A platoon from the 1st Battalion, The Black Watch, pose for the camera before going out on patrol in 1952.

Stalin was looking at the bigger picture. He wanted to keep the US and her allies pinned down in East Asia in order to give the communist powers in Europe the chance to re-arm and consolidate themselves. The war was essentially a ‘diversion’. Korea became a place where he could distract the US and her allies, using huge amounts of Chinese manpower and a few of his own MIG15 pilots. Ironically, it was North Korea, Soviet’s ally, that took the brunt of it all: the end of the War, 80% of all its buildings were destroyed. The phrase ‘bombing back to the Stone Age’ should first be applied to North Korea. But Mao also benefited. He lost an a lot of ‘volunteers’ in the fighting, but was flexing his muscles. The Korean War gave the new ‘emperor’ of China an opportunity to scare his neighbours, especially Nationalist Formosa, or Taiwan, as it now is known. He also got to modernise his army. At the end of the War, the Chinese military was infinitely more effective than at the start.

Up there, beyond the DMZ, they say they won the War. It’s called the Fatherland Liberation War. They also say that the South invaded the North. Which means that one must assume that the people of North Korea are today celebrating a war which they believe was an invasion that they repulsed and that became a heroic and triumphant war of liberation. The truth, of course, is very different. But not simply the opposite of the rhetoric deployed by the government of North Korea. In some senses, the South did coax the North into conflict. The period from spring 1948, when the two Koreas officially came into existence up to the outbreak of hostilities was characterized in the the South by widescale persecution of anyone who showed sympathy for the DPRK. On Jeju island, which lies off the south coast of the peninsula as its now known as ‘Honeymoon island’, between April 1948 and May 1949, somewhere between 14,000 and 30,000 people (10% of Jeju's population) were killed, and 40,000 fled to Japan. In some ways, this was the true beginning of the Korean War.

In today’s ‘Korea Herald’ it was announced that a conference of Korean War veterans will be held in Pyongyang, despite the Covid-29 epidemic, of which, so they officially say, there are zero cases. No one outside North Korea believes this, but one of the problems with consistently lying is that even if you decide to tell the truth no one will believe you. Perhaps the draconian measures they’ve taken have indeed kept out the virus. But at what price? Meanwhile, the economy is imploding and the people are starving to death. Yesterday in the same newspaper it was reported that more foreigners have left the country because of the severe restrictions, which means there are now hardly any non-North Koreans remaining in the DPRK. Sometimes I fear that a Jonestown-style mass suicide is in the offing. It isn’t so implausible. After all, the people are so wholly enmeshed within the bizarre alternative reality manufactured by the Party that they may very well willingly follow orders that require them to make the ultimate sacrifice.

42%

The lie that hides the truth.

The UN recently reported that 42% of North Koreans are undernourished. One in five North Korean children suffer from malnutrition. This puts the DPRK on par with places like Somalia, the Central African Republic, Haiti and Yemen. What makes the DPRK different from these other nations, however, is that just across the border there is another nation that only seventy years ago began with the exact same people, the exact same history, the exact same geography, the exact same material advantages and disadvantages, and yet today has the tenth largest GDP in the world!

How to make sense of such a tragic anomaly?

First of all, historically, it wasn’t exactly such a level playing field, but not in the way you might expect. For during the Japanese colonial period (1910 – 1945) the focus was on the industrialization of the north of the peninsula more than the south. Furthermore, the northern part has more natural resources, such as coal. In other words, from the moment of the establishment of the DPRK and the ROK in 1948, and after the Korean War (1950 -53) - and despite the devastation wrought by the UN carpet-bombing of the DPRK - it was the DPRK who was more economically advanced that the ROK until the 1980s. This, however, was not simply because of innate infrastructural and material advantages. The DPRK also benefited greatly from the patronage of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries. Meanwhile, the ROK got similar benefits from its close alliance with the United States. The crunch came in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union, at which point the DPRK the sudden withdrawal of material support threw the DPRK into an economic crisis, exacerbated by adverse weather conditions in the 1990s which led to a famine in which perhaps as many as 3.5 million people died.

This news about the numbers of undernourished in North Korea makes one see the power of ideology over life. Ideology does not only determine what we think and how we behave, but also directly impacts on our bodies. The average North Korean kid is stunted in growth. The average height of a North Korean adult is between 3. 8 cm (1.2 – 3.1 inches) shorter than their South Korean neighbours! This means that the same gene pool, the same ethnic group has within a very short period been physically manipulated by the social system under which people live. This is true of both Koreas, because South Koreans are now taller than seventy years ago due to the change in their diet.

An image of the Pyongyang subway from Oliver Wainwright’s book Inside North Korea. The lucky 58%.

But the situation in North Korea is more complex than the statistics suggest. While 42% are undernourished, these citizens are almost entirely in the countryside, and not in the capital Pyongyang, where the regime ensures that residents have a higher standard of living in return for loyalty. For only those who have proved themselves complaint and obedient are permitted to live in there..

In a previous post I mentioned Yeonmi Park, who escaped from North Korea. As a child living near the Chinese border, she endured the famine of the 1990s, and she graphically conveys the experience of malnourishment, which reduces life to a daily struggle to simply find enough to eat. Hunger effectively crushes any other dimension of human existence.

Park reminds us that pretty much all our thoughts are luxuries, in the sense that they are surpluses to the basic survival instinct. If I think of my own life, one in which I have never felt undernourished, I can see that the society in which I live and the social status I have within it, has permitted me to spend a very indulgent life, one in which I have been able to enjoy freedom of speech, and to explore at leisure the ‘meaning of life’, love and affection, travel, art-making, writing, mentorship of students. My life, in short, has been one of enormous privileges that I more or less take for granted.

As Yeonmi Park noted, outside Pyongyang keeping people hungry is a useful weapon, as it also keeps them too weak to protest. Therefore, the mechanisms of power employed by the ruling Party functions on the level of both the mind and the body. Brainwashing, on the one hand, and undernourishment on the other. This is not to say that the Party actively encourages food shortages and famines. But they clearly do not see it as an overwhelming obligation to make sure everyone under their control has enough to eat, because what is deemed of paramount importance is not individual citizen’s survival but the survival of the Party system. As a functionary recently announced, they reject aid from the United States because they observe that many countries ‘have undergone bitter tastes as a result of pinning much hope on the American aid and humanitarian assistance.’ This is true, in that, as they say, ‘there’s no such thing as a free lunch,’ a sadly apt metaphor in this case. But as the US State Department observed: ‘the DPRK has created significant barrier to the delivery of assistance by closing its border and rejecting offers of international aid, while also limiting the personnel responsible for implementing and monitoring existing humanitarian projects’.

The North Korean concept of juche – self-reliance – isn’t intended to mean survival of the fittest. Far from it. The idealization involved in the concept means that the DPRK is said to guarantee succeed by achieving national autonomy, independent development. But as history shows this is an absolutely fatal error of state policy. China and Japan tried it, as did Korea under the Joseon dynasty, which closed its doors to the rest of the world for centuries, and became known as the Hermit Kingdom. These countries all failed in their efforts to resist the forces of globalization spearheaded by the Western powers, and ended up being forcibly driven to sit at the table of world trade and Westernizing modernization. Japan capitulated first, and even copied the imperialistic agenda of the Western powers by annexing Korea in 1910 and Chinese Manchuria. Seen in this light, the DPRK’s stance can be seen as a throwback to before this fatal moment when East Asian countries encountered the West and eventually found that they had no choice but to succumb to their influence.

The different decisions of the leadership in the People’s Republic of China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea are instructive. The Chinese Communist Party eventually saw the writing on the wall, and after the period of Mao, during which an attempt at Chinese self-reliance proved disastrous, chose once again to engage with the rest of the world. The fact they have spectacularly succeeded and maintained and even enhanced their control over China is testimony to the fact that today modernization no longer entails what the historian Niall Ferguson in his book Civilization. The West and the Rest (2011) rather faddishly describes as ‘downloading’ all the West’s ‘killer apps’, which include individualism and democracy, and instead can mean only an obsessive focus on others of these ‘killer apps’ – industrial productivity and consumerism.

Clearly, the DPRK is not ‘downloading’ any of the West’s ‘killer apps.’ By a tragic quirk of history, the Korean peninsula ended up being divided between the Soviet Union and the United States and its allies in 1945, got partition along the 38th Parallel (which is just a few miles north of where I write this post) as a pragmatic solution to an immediate problem, but thereafter tragically condemned one half of the people of the peninsula to a system that, while for a while seemed a viable rival to the West’s ‘killer apps’, remarkably quickly proved a total failure. add to this the continuing dominance of the United Staes over global affairs, and we have this result: 42% of North Koreans are condemned to a life spent foraging for grasshoppers on the mountainsides just to stay alive.

Even more on a North Korean at Columbia University

I can’t resist mentioning one final time the sad experience of Yeonmi Park , the North Korean defector who went on to study at Columbia University and ended up feeling she’d wasted her time.

I have been reading the German literary critic Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht’s Production of Presence. What Meaning cannot Convey (2004), and came across this discussion of the appropriate role of education today:

If…confrontation with complexity is that which makes academic teaching specific, then - instead of attributing meaning and thereby providing solutions - we should seek to practice our teaching, as much as possible, in the modality of lived experience (Erleben). For good academic teaching is a staging of complexity; it is drawing our students’ attention toward complex phenomena and problems, rather than prescribing how they must deal with them. In other words, good academic teaching should be deictic, rather than interpretative and solution-oriented. But how will such a deictic teaching style not end in silence and, worse perhaps, in a quasi-mystical contemplation and admiration of so much complexity?…..[The answer involves] the never-ending movement, the both joyful and painful movement between losing and regaining intellectual control and orientation - that can occur in the confrontation with (almost?) any cultural object as long as it occurs under conditions of low time pressure, that is, with no ‘solution’ or ‘answer’ immediately expected. (p.127-128)

Well, it seems obvious to me the academics at Columbia, like elsewhere, seem to be trading in complexity for simplicity. They prefer to teach clearly interpreted scenarios not open-ended uncertainty. Under political pressure to narrow the gap between the ‘ivory tower’ of academia, which, as Gumbrecht puts it, functions ‘under conditions of low time pressure’, in other words, under pressure to make themselves ‘useful’ in a time of crisis, academics no longer have faith in the importance of functioning within a social space in which ‘no “solution” or “answer” [is] immediately expected.’ (128)

Gumbrecht goes on to discuss how his assertion parallels that of the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, who characterizes the university as a ‘secondary social system,’ that is, ‘a social system whose function should be the production of complexity - in distinction from and in reaction to most other social systems, which Luhmann saw as being oriented toward the reduction of complexity offered by their environments.’ (129). Gumbrecht also cites a Max Weber essay from 1917, in which Weber urges academic research to be about ‘“unpleasant facts,” counterintuitive insights, and improbable findings’. (129)

This is no longer the role of academia. Too much offense will be caused by willful intellectual peregrination., too much damage to others’ self-esteem.

It also goes without saying that as the Internet is now a principal arena of social discourse, and this medium cannot tolerate complexity of thought, what is also happening is that academia has assimilated itself to the same crude protocols.

in other words, academia is in the process of giving up its role as a ‘secondary social system.’ But what we need - as a matter of life or death - is just such a space dedicated to the exploration of complexity, a space where solutions and answers in the real world are not forthcoming. A space in which Yeonmi Park might have been able to develop here newly and painfully won capacity for critical thinking, and insatiable appetite for freedom of expression.

The First Pictures of Roses. Part I.

Chauvet Cave, south-west France. The painting are c.35,000 years old.

Roses have been around for millions years, but when did they first start attracting human interest as well as bees? When did they become worthy subjects for pictures?

The first recorded paintings were made by Upper Paleolithic humans in the darkness of caves around 40,000 years ago, and they give some idea of what interested Ice Age humans. From the evidence, they drew both abstract signs, often ‘geometric’, and realistic depictions of animals.

But the consensus is that there are no obvious images of plants or trees, or indeed of any landscape features. Why should this be? After all, the survival of these humans absolutely depended on their intimate understanding of the entire biological and geographic environment. These were small groups of nomads that survived by hunting game and gathering plants. They must therefore have been very intimately involved with plants, which they used as foodstuff, tools, and ornaments, and also perhaps as medicine, hallucinogens, and grave offerings.

But there are no obvious pictures of flora, in the way that there are images of fauna. The horses, lions, bison and so on, are not even depicted running along the ground, and move as if existing in some kind of horizonless habitat liberated from the vegetal and geological setting. Paleolithic humans focused their attention intensely on animals, and their paintings display a very accurate knowledge of their form and behaviours.

We also find lion-men (or men-lions) but never tree-men (or men-trees). Ice Age humans didn’t seem to link knowledge of the vegetal world to knowledge of the human social world, but they did make such a connection in relation to the animal world. When one looks at the horses and lions in Chauvet cave – the oldest known cave-paintings in Europe – one has a powerful sense that the animals have been personalized. Humanized. Anthropomorphized.

One possible reason for the absence of realistic pictures of plants is prosaic. In the Ice Age plants were far less bountiful and varied than now. Outside the caves in which Paleolithic humans painted, the vegetal environment was barren. There would have been hardly any trees, for example, and certainly there would have been no roses growing in Europe, where most of the cave-paintings are located, although roses already existed in warmer climes. The Ice Age landscape would have looked rather like the Siberian steppes. Fauna, by contrast, was plentiful and roamed freely across the vast open spaces. In other words, perhaps Paleolithic era plants simply weren’t that interesting to paint. But this doesn’t seem like a convincing explanation.

Evidently, plants were also not very interesting to ‘think’, to use a concept of the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss. If, as psychologist now believe, one of the most significant aspects of the human mind is the capacity to learn from mimicking others – human and non-human - then the origins of art may lie in the desire to contemplate what it was worth mimicking in other animals. Art’s origins lie in mimesis - imitation - in the sense of copying something as an image, but this practice was worthwhile only because of the importance of copying the animals behaviour and desires. Making images allowed humans to transmit messages across time concerning valued animal behaviours, so that they could be better consolidated culturally as modes of imitation. Humans imitated each other, but also horses, lions, etc. to learn who they were as humans through recognizing their similarities and differences from these animals.

This mimicry was also capable of being elaborated. It seems Ice Age people copied, for example, the actions of another some-time biped, the cave bear, who scratched on the wall of the caves they hibernated in. Many human paintings seem to have been deliberately made over such clawing, such as these in Chauvet Cave:

They then extrapolated from the cave bear markings using their far more sophisticated mental capacities which involved thinking across different cognitive domains. In other words, they used their imagination.

But it seems possible that this initial mimicking action in relation to cave-bear scratchings led off in two directions: towards relatively similar forms of graphic marking, that is, to an abstract sign system, and also, much more radically, towards realistic pictures.

Interestingly, one of the aspects of animal life that seems to have especially preoccupied Upper Paleolithic humans was the ability of animals to move. The painters came up with a remarkable vocabulary of visual tricks for mimicking movement in static images, using the irregularities of the cave walls, the play of torch light, and even painted legs and heads as if seen at different moments in time, like time-lapse photography. Their acute responsiveness to movement suggests an obvious interest in something animals have in common with humans, who are relatively slow moving bipeds when compared to the four-legged lions and horses that were a common subject of cave-paintings. The ability to make a static shape mimic not only an animal form but also its movements demonstrates the amazing power of the human imagination to transform something into something else. The human-animal figures, known as therianthropes, for example, clearly suggest that Ice Age humans were able to imagine things that did not exist in the world. This ability to imagine the impossible, the fictional, is surely one of humanity’s most important strengths - in terms of natural selection, a truly unrivaled advantage.

So while animals were significant in relation to affirming the values of human life through the establishment of clear relationships of sameness and difference, plants existed apart, in a realm in which transfers of meanings did not so readily occur. In other words, humans are fauna, not flora. So they lack the same obvious commonalities, which made it easy for humans to mimic other animals.

But let’s consider the abstract signs that are also prevalent in cave-painting sites. There are 32 distinct types of these symbols that were re-used over a period of 30,000 years. Could some be landscape features, and even flora?

Take a look at this example:

It is in El Castillo Cave in Spain. Here you can see what is known in paleoarcheology as a ‘penniform’ (Latin for “feather”) sign in black. It is surrounded by five bell-shaped signs in red. Doesn’t it look like a tree or a typical plant-like morphology?

Here are some more signs in La Paseiga cave in Spain. Could they be seed pods, flowers, or leaves?

In her book ‘The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols’ (2016) Genevieve von Petzinger catalogues the signs she discovered:

How many of these could be signs for plants based on schematic renderings of their morphologies, seed forms, flowers, and leaves?

But not a rose. For, as I mentioned, there would have been no wild roses growing in Ice Age Europe.

What is fascinating about the abstract signs in the caves is that they are a form of graphic communication that is proto-writing. What they share with the realistic images of animals (and rarely, humans) is that they transmit messages across time. But while the messages sent by the animals seem relatively receivable to us, the abstract signs are not.

Even if the abstract signs are plants, what did they mean? It seems clear they weren’t just decorative. Unfortunately, we will probably never know.

In a future post I will consider the arrival of plants as an important subject in the art of the Agricultural Revolution.

NOTES

Genevieve von Petzinger 2016 book is The First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols.

You can watch the author giving a TED talk here: https://www.english-video.net/v/en/2377

More on a North Korean at Columbia University

After I’d posted my previous post, I was mulling over other possible causes of the pervasive hostility to Western civilization of tenured radicals in our universities, and came across this choice quotation from the German novelist Thomas Mann:

Deep in our hearts we felt that the world, our world, could no longer go on as it had. We were familiar with this world of peace and frivolous manners……..A ghastly world that will no longer exist - or will not exist once the storm has passed! Wasn’t it swarming with vermin of the spirit like maggots? Didn’t it seethe and stink of civilization’s decay?

Mann wrote these words in 1914 in an article called ‘Thoughts in Wartime’ in which to the surprise of most of his admirers he declared himself a fervent German nationalist and militarist. Just in case anyone thought this to be a momentary aberration, Mann went on to make his belligerent position even more explicit in Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man (1918).

My attention was drawn to the quotation by Mark Lilla’s essay about Mann in a recent issue of the New York Review of Books (1). I was struck by how Mann’s celebration of the cleansing destructiveness of war chimes with the more extreme ‘Wokeist’ tirades against ‘Western civilization.’ Although the circumstances are very different, there is a link between now and then in the underlying contempt for liberal humanist culture, and the atavistic urge to destroy that seems to pervade radicalism so that something better can rise from the ashes.

As Lilla points out, Mann succumbed to the clichéd opposition between decadent ‘civilization’ and authentic ‘culture,’ defending the virile latter, which is in danger of being destroyed by the ‘effeminate’ pretensions of the former. These old tropes are no longer credible but a new kind of distinction is being made today, which seems to line up both Western ‘civilization’ and ‘culture’ against the same wall ready for the firing squad of identity politics..

All roads lead back to Friedrich Nietzsche. It was Nietzsche who most famously celebrated ‘creative destruction’ for its regenerative energies. The new morality must stand on the ruins of the old. In Thus sake Zarthustra, Nietzsche declared; ‘Whoever must be a creator always annihilates’. It seems certain that, like so many young men in Europe, Mann breathed the heady perfume of the Nietzschean celebration of war that pervades Zarathustra, lapping up in phrases like this: ‘Your enemy you shall seek, your war you shall wage – for your thoughts. And if your thoughts be vanquished, then your honesty should still find cause for triumph in that. You should love peace as a means to new wars – and the short peace more than the long.’

Now, I’m of course not saying that those protesting against the inequities of Western civilization and culture today are baying for war. What I mean is that they too have inherited a powerful strain of the Nietzschean virus. In other words, they recognize the degeneration of the West is such that nothing less than a cultural earthquake will bring about change for the better. Nietzsche was demanding shock therapy because he believed that a better world was possible. His stance was not so much negation for its own sake as an affirmation of what could be. Things as they are must be assailed relentlessly. For Nietzsche, this was partly because he believed challenge and opposition were valuable in their own right as they foster strength. But more importantly, it was because he believed that through destruction the new will be brought into being. In the same way, the advocates of diversity, inclusivity, and equity see affirmation as necessarily requiring negation. The problem is that, just as was the case with Nietzsche, ‘Wokeism’ seems much more eloquent, versatile and persuasive in relation to the task of tearing down than it does in designing the architecture for a better society. Destruction eclipses creation.

For Nietzsche, as for Mann, part of the problem was that the artist had become too politically engaged, and had forgotten the true calling of art, which stands apart from the realities to which politics draws attention. Today, the reign of the politics of identity within the arts has collapsed any faith in their capacity to have value and meaning in themselves apart from in relation to issues of social diversity, inclusivity and equity. It isn’t just that the rarefied ideas of ‘art-for-art’s-sake’ or formalism have been abandoned, it’s that as a set of social practices the arts are no longer considered to have cultural significance on any other level than that of identity politics.

Notes:

Mark Lilla, ‘The Writer Apart’, NYRB, May 13, 2021.

A North Korean at Columbia University

Jordan Peterson talks with Yeonmi Park on his YouTube blog.

As one high-raking North Korean defector put it: “[O]ur General’s life is a continuous series of blessed miracles, incapable of being matched even by all our mortal lifetimes put together.” Because of the total monopoly of the Kim dynasty-centric narrative, every North Korean’s life unfolds within a drastically circumscribed and impoverished reality. The ludicrous fantasies that smother North Korean culture in a stultifying miasma seem obviously nonsensical, but let’s not be too quick to believe that we in the ‘free world’ are not also in danger of our own insidious forms of psychologically flattening indoctrination.

This awkward truth has become especially clear to me recently through watching the Canadian academic, psychologist, and best-selling author Jordan Peterson’s podcasts on YouTube. Peterson is a controversial figure, and many on what he likes to dub the ‘radical left’ disdain him because his comments have been too easily picked up by the so-called ‘alt-right’ and made to sound racist and sexist. As far as I can tell, Peterson is genuinely trying to plough a straight furrow between extremes, appealing to scientifically verifiable data and common sense. But this is not a time to be ploughing such furrows, nor is his conviction that scientific data speaks ‘objectively’ for itself unproblematic, not least because all to often Peterson seems to smuggle in his own strongly subjective opinions under the cover of assertion that ‘the data speaks for itself.’ Maybe he is just doomed to fail, became this is a time of polarization, and however well-meaning his attempts to draw attention to the more extreme consequences of cultural relativism, Peterson cannot avoid being co-opted. For example, it is clear that one of the platforms he has opted for and utilizes obsessively – the YouTube blog – is inherently polarizing, and nuanced positions like his simply cannot be maintained once large audiences engage with them.

Many of the people Paterson interviews tell him stories of how core cultural institutions like the university and the press within which they work have become ideologically entrenched, and are now dominated by the new puritan zealots of what is dubbed ‘Wokeism’ , that is, dominated by people who embrace the sanctity of diversity, inclusivity, and equity above all else, and ironically often pursue these goals with overtly intransigent, aggressively adversarial, and condescending zeal. As an academic working in South Korea, I feel distanced from the culture war raging in the West, and it’s hard for me to believe that what Peterson warns about really is so threatening to the future of the open society. But a recent interview made me really sit up. In it Peterson talked with Yeonmi Park, a young woman (born 1993) who escaped from North Korea and subsequently wrote a book about her experience entitled In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl’s Journey to Freedom (2015)

What Park went through is harrowing. Her life as a child in North Korea was a brutal struggle for survival, but nevertheless she managed to escape to China when she was a teenager. But once she and her mother got there they were immediately enslaved – sold to Chinese farmers who were in need of wives. Eventually, after much more suffering, in which she contemplated suicide, Park arrived in Seoul, and through sheer determination completed her high school education in record time and then went on to university. She talked to Peterson of the importance for her of George Orwell’s book Animal Farm, which made her aware of the extent to which the North Korean system had robbed her not just of freedom but also of possibilities inherent in the very concept of freedom. For Orwell recognized that the surest way to control the minds of people is to control the language they use. If they don’t know how the word ‘freedom’ can be used, what it can mean, then they won’t know that they lack it. For ‘freedom’ is an abstraction that only becomes real through the deployment of tangible analogies and metaphors. If these tangible references are corralled into a controlled and circumscribed narrative, then the abstraction exists only in relation to the key actors within that narrative, which in the case of North Korea is only one: the Kim dynasty narrative. So, freedom as a concept is only understandable in relation to the dominant Kim narrative, where it comes to mean something very different from how we think of it. In this way, and also through the more punitive expedient of keeping people hungry in the provinces, the North Korean system systematically reduces its citizens to ox-life compliance.

Inspired by Orwell and other such cultural lighthouses in the West, Park ended up enrolling at Columbia University in New York, and it was what she said about her experience there that was an especially surprising and dreadfully demoralizing part of the Peterson interview. For she had concluded that her three years of study were a complete waste of time. Why? Because she found not the support, encouragement, and an invitation to explore the open society but rather a terrible closing down of the intellectual mind. All her humanities’ professors – all – were in such thrall to the political correctness of diversity, inclusivity, equity advocacy that they displayed a pervasively antagonistic attitude to Western society that deeply alienated Park. She mentioned how one female professor chided her for allowing a man to open a door for her, and when Park insisted that she believed he had done so in good faith, the professor insisted that Park was sadly brainwashed by the patriarchy. Park had come to Columbia in order to continue to reap the benefits of cultural emancipation, and instead she found the intellectual elite in the West had lost faith in the very culture of which she had enthusiastically and gratefully placed her own faith as a bone fide life-saver.

You could plainly see in the interview how ashamed Peterson felt about Park’s disappointment. I felt ashamed too. Here was a young women who had gone through hell, and, against impossible odds, and fired by an appetite for freedom and knowledge, had got to study at Columbia. Here was a young woman whose will to survive was fired by faith in an at first inchoate and then copiously corroborated benefits of the broadly humanistic values of the open society, values she had come to believe were universally binding beyond the nightmarish reality of North Korea, only to find that the most coddled intellectual elite of the West, who have had no experience of the deprivations Park was born into, patronizingly informed her that she should realize above all else that the West is systemically racist, sexist, and predicated on the arbitrary exercise of power.

This manic compulsion amongst elite intellectuals to criticize and condemn is being stoked by many factors. I think Yeonmi Park’s disappointment should make us consider what role is being played by the extreme contrast between her own awful early life experience and the lives of the tenured radicals who felt justified in preaching at her. Could it be that these intellectuals feel guilty about their privilege, and that they try to hide the fact by taking up the cause of the oppressed and pushing their critique to an extreme?

Could it also be that their sheltered existence, their good fortune in living in a society that, despite the terrible injustices and inequalities that certainly exist, has been remarkably peaceful in their lifetime, has made them lose any sense of what is at stake in denigrating their culture to the extent they do? In lambasting humanism and baying for revolutionary change they betray the extent to which they lack personal experience of how fragile is the civilization that cossets and protects them. It’s easy to advocate revolution from an armchair one has never been thrown out of.

The phenomenon of cultural polarization also signals the overwhelming tribalism of human sociality, even of its elites. Individual member of a socially integrated group do not want to risk breaking rank on fear of being accused of the unforgiveable, and getting ostracised. Another of Peterson’s interviewees told a very sad story of her suspension with pay from a tenured position at a Canadian university because of what, on the face of it, were very innocuous comments made on her blog that drew ire from a few students as racist and sexist. The fact that the person accused is a female Muslim immigrant from Lebanon should give one pause for thought. It seems that within the present climate, the most dangerous figures are those cast as heretics, that is, those who should be content and grateful to follow the dominant line but refuse to do so.. What was especially disheartening was that none of this woman’s colleagues have publicly come out in her support. What cowardice! In this context, the ‘scapegoating mechanism’, as the cultural critic René Girard, terms it, which I discussed in a previous blog, is also an important causative factor. In times of crisis, groups seek to shift their anxieties onto a nominated ‘guilty’ party, which then carries and carries way their anxiety through being sacrificed. As Girard notes, for the ‘scapegoat mechanism’ to work, the accusers must be totally convinced of their scapegoat’s guilt, who when viewed from outside the dynamics of the mechanism, is seen for what it really is: an innocent sacrifice.

But to understand why no one wants to break ranks we need to delve deeper that just fear of being ostracised or being made a scapegoat. A more systemic or deep structural way of explaining the situation seems to me to be to view Park’s story as an individual instance, a particularly dramatic instance, of a much more generally pervasive and longstanding cultural phenomenon in the West. What I mean is that Park’s life is in a sense a speeded-up version of what the sociologist Max Weber recognized as the central drive of modernity on the level of values and meaning: disenchantment. In a decade, and on a very personal level, Park has gone through what our society as a whole went through over a period of at least two centuries. We can consider her as experiencing on a very personal level in a decade or so the entire Enlightenment ‘project,’ in the sense that she emerged from the darkness of prejudice and superstitious into the light of reason.

But this is not where the heroic ‘project’ ends. The process of disenchantment is like a tidal wave that gathers force as it demolishes traditions and beliefs, and the logic of disenchantment is actually perpetual disenchantment. In other words, continual and relentless critique. It is therefore inevitable that values and beliefs will be continuously overturned. As loyal heirs to modernity in the cultural realm the intellectual elite in the university and elsewhere must therefore continue the struggle of critique, even though it will eventually involve devouring their own children, because this loyalty is to the ‘not yet’, to a deep sense that the world as it is always deficient.

When seen in this light, Park is still intellectually at the stage the intellectuals in the West were at over one hundred years ago. She believes in humanist universalism, just like most of the intellectual elite once did. But for those most unreflectively committed to the ‘project’, this belief was just a way-station, because it was actually premised on the deeper impulse to critique and reject, which was initially directed at the pre-scientific religious worldview and the values of the pre-industrial aristocratic hierarchy. But the logic of disenchantment mandates a process of endless critique., something that was most evident first in Marxism, and then later transmuted into the critical impulse became enshrined in ‘post-structuralism’ or ‘postmodernism’, and now is encapsulated in ‘Wokeism’.

This is the logic of critique as a mode of historical consciousness, and it means that while the hinge of the critique may today be identity and diversity-inclusivity-equity, this is not actually what is really driving the protests. For the underlying motivation is disenchantment as a belief system, a mode consciousness, as guiding principle. In this sense, one could even argue that it really doesn’t matter what is being ‘disenchanted,’ because what is important is the will to disenchant, whose logical end can only be the tabula rasa – the blank slate. Only when there is nothing left to disenchant can the process cease. If this sounds nihilistic, that’s because it is. In this sense, however justifiable the struggle for justice may be it also conceals an underlying nihilistic will to reach a tabula rasa. Wokeism should really be called ‘Blank Slate-ism.’ This is certainly not to deny that obviously justifiable grounds exist for confronting social iniquity, but what I am arguing is that there can be an underlying dynamic to such protests that lies within a deep cultural phenomenon - a historical consciousness - which effectively turns the protest for justice into a cultural Terminator. Yeonmi Park has refused to adopt this next stage in the logic of disenchantment for obvious reasons. She is still in the first flush of a prior disenchantment, having freed herself from North Korean ideology. Will she resist the subsequent stages? Much depends on what kind of intellectual community she choses, who she admires. But it seems fair to say that it won’t be a community consisting of Columbia University professors.

A final reason for the stance adopted by increasing numbers of our intellectual elite is defensive and perversely therapeutic. This is a n age pervaded by an extreme sense of vulnerability caused by a confluence of factors over which we have very little control. Above all, ecological disaster poses a vastly more dangerous threat to humanity than the problems that Wokeism draws attention. When viewed in this context, the controversies over identity politics look like powerfully compelling distractions from a far more fundamental crisis, one which we have really no idea how to confront.

I end today’s post with a quote from Jonathan Lear’s book Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation (2006):

We live at a time of a heightened sense that civilizations are themselves vulnerable. Events around the world –terrorist attacks, violent social upheavals, and even natural catastrophes—have left us with an uncanny sense of menace. We seem to be aware of a shared vulnerability that we cannot quite name. I suspect that this feeling has provoked the widespread intolerance that we see around us today –from all points on the political spectrum. It is as though, without insistence that our outlook is correct, the outlook itself might collapse. Perhaps if we could give a name to our shared sense of vulnerability, we could find better ways to live with it (p.7).

The Korean Dead

In today’s post I want to talk about death. Well, the burial of the dead. Within a square mile of my house there must be over a hundred grave mounds scattered around the hills, some quite elaborate but most very simple. I recently went on a walk and photographed some of the ones I passed.