Immune System. East and West

In relation to Covid I’ve been hearing a lot about our ’immune system’. Don’t worry about face masks or vaccines. if you want to protect yourself against Covid just boost make sure you your immune system! What might a cross-cultural analysis of this notion have to say about cultural difference?

Covid certainly isn’t going away. Friends and colleagues both here in Korea and in the UK recently have been or are currently unwell with the virus. I’ve had it twice. Will I make the hat-trick? So, although we are now acting as if the pandemic is over, it’s not. We’ve just normalized it, now we know the virus doesn’t represent an existential threat to our society. In the meantime, I’ve been hearing a lot about our ’immune system’. Don’t worry about face masks or vaccines. if you want to protect yourself against Covid just boost your immune system!

Wikipedia says: ‘The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinters, distinguishing them from the organism's own healthy tissue.’’

It seems to me that in the context of Covid (or any other potentially pandemic causing pathogen) we are wrong to just limit a useful notion of ‘immune system’ to the individual biological organism. Although, as the definition demonstrates, the term obviously relates in a very concrete way to our own bodies and refers to a system that where the hair follicles and skin create a boundary between us and the outside world, we would surely do well to recognize how our distinct corporeal body is inevitably connected to the wider environment, both human and non-human. So, really, we should be conceiving of the ‘immune system’ in systemic terms, that is, as referring to a network of which our own individual biological immune system is just one integral part.

But whenever people say ‘boosting the immune system’ they only seem to mean their own. As if they exist in a bubble. I would wager Westerners are more prone to this very limited notion than Koreans and other East Asians, or people who live in more collectively rather than individualistically oriented societies.

One way of understanding how this might be true is to consider the distinction made by the philosopher Charles Taylor (whom I’ve mentioned on more than one occasion) between the ‘buffered self’ and a ‘porous self’. Taylor limits himself only to the historical analysis of Europeans, arguing that there has been a shift from the pre-modern ‘porous self’ who is conceived as being interrelated with others and the world, to the modern ‘buffered self’, which has more autonomy, and acts as if a separate and discrete individual entity.. A cross-cultural version of this is suggested by another philosopher, Thomas Kasulis, who argues that there are two ways of being in the world – what he calls the ‘analytical’ and integral’ (West), the other the ‘holistic’ and ‘intimate’ (East Asian). These terms emphasize the difference between the idea of an autonomous, individualized conception of the self, and one that is more interdependently conceived. Obviously, these self-representations are not rigidly culturally distinct. In our globalized world they are converging and blurring to produce new ways of being. In Korea, its clear that the individualistic ‘buffered’ ‘integrated’ self is fast superseding the more traditional, and Confucian, ‘porous’ self, or perhaps blending to become something between ‘porous’ and ‘buffered’. A ‘filtered self’, perhaps?

I’ve already discussed in my blog how this this distinction impacted on attitudes to face masks. It might aslo help explain variations in ideas about ‘immunity’. An ‘integral’ self would limit the idea to the physical or biological body, while the ‘intimate’ self would more readily extend any notion of ‘immunity’ to the transpersonal. If you consider that your ‘immune system’ extends to the social body, not just your own body, then it would be ridiculous to only talk about making sure you take exercise, eat citrus fruits, spinach, almonds, papaya, and green tea, and get enough vitamin A, C, D, and E, and selenium and zinc. These are important, of course, but you wouldn’t stop at concerns that are limited to what lies within the boundary of your own body. When you thought of ensuring effective immunity you would want to make sure you were linking your own immunity to that of others by, for example, wearing a mask and getting vaccinated..

NOTES

The image in today’s post is from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320101

The Wiklipedia quote is from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immune_system

I refer to:

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2018)

Thomas Kasulis, Intimacy and Integrity. Philosophy and Cultural Difference (University of Hawaii Press, 2002)

The Public and Private

In this post, I want to go back to something I promised not to mention again: face masks. I apologize for breaking my promise but hope you will find what I have to say adds something interesting to my on-going exploration of cultural differences between the West and Korea. These reflections come after having spent the past month and a half in Europe.

After my stay in my house in France I was in London for ten days. The main purpose of my visit was to install an exhibition I helped curate and in which I exhibited. It’s called TRANSFER and is at the Korean Cultural Centre UK until April 15th. The picture at the head of this post is of me at the Opening. If you’d like more information, here is a link: https://kccuk.org.uk/en/programmes/partnership-programme/transfer/

But in this post, I want to go back to something I promised not to mention again: face masks. I apologize for breaking my promise but hope you will find what I have to say adds something interesting to my on-going exploration of cultural differences between the West and Korea.

*

It’s always a massive culture shock to be back in Europe after months in Korea, especially since the pandemic. Now that Covid-19 is far less threatening, life in Europe looks like it’s trying to go back to the familiar old pre-pandemic ways. In Korea, however, we are not permitted to forget so easily the virus’ continued presence in our midst.

The most obvious contrast is, as I already noted (more than once), in the attitude to face masks. Almost no one wears them anymore in Europe, not even on the crowded Metro or Tube, whereas in Korea they are still everywhere. The persistence in masking-up outside was bizarre to me because the Korean government decreed in May 2022 that it was no longer mandatory to wear them outside, and yet the Koreans went on doing so. The only Koreans you saw not wearing masks on the city street were foreigners on visits, and some younger Koreans who, I assumed, were sufficiently ‘Westernized’ to consider breaking ranks with their compatriots. This put me in an interesting cultural dilemma: did I do what my fellow Westerners were doing, or my fellow Koreans? I tended to side with the Koreans out of the belief that one should try to respect the norms of the place one is in. But evidently, the Westerners who went mask-free were not troubled by this obligation, and only wore their masks when they knew it was legally required.

It’s still necessary to wear a mask on public transport. But on my return in early March, I find that many more Koreans are now walking mask-free. In late January, the indoor mask mandate was also finally lifted. But far from jumping at the chance to throw off their masks, Koreans still seem reluctant to comply with this freedom.

Whenever I mentioned the fact that Koreans were voluntarily wearing masks to people during my visit to France and Britain, they said the exact same thing: “Oh, the Koreans are used to wearing mask.” That is, they wore them pre-Covid because of pollution or because they were sensitive to the risk of contagion when they were sick with a cold or flu. This is certainly true. But I can’t help thinking that much deeper factors are involved.

I now see the face mask issue in term of the relationship between the public and private realm – of the relationship between the self as a public and private entity. There seems to be a fundamental difference in the way these two realms relate to each other between Korea and the West.

By ‘private’ self I mean the one that loves and hates, fears and desires. This is a self that is essentially invisible to the world. It is the subject’s consciousness. By ‘public’, I mean the self that one presents to the world, that performs duties within society, the one that is visible to others, and is characterized by specific social signifiers. The level where private and public intersect is what we call ‘identity.’ Here is a typical diagram of how this works:

Historically, a society’s stability rested on the strict policing of the boundary between these two realms, so that people’s identity remained stable, and so did society’s. But with the advent of modernity, the boundary began to become much more flexible or permeable. The ideal of the free private individual seeking their ‘true’ or ‘authentic’ identity supplanted that of subordination to the collective, with the result that the private realm took on more and more public importance. This was especially the case once capitalism moved from its productivist to consumerist phase. When one is a producer, one is primarily a social self, but once one becomes a consumer the private self is increasingly implicated. This is because consumerism is based on desire.

In the West today the public and private are all mixed up – and are becoming ever more so. Here in Korea, by contrast, the division between public and private selves is still much more strictly demarcated, but also under threat.

We are already familiar with the tendency of Westerners to dress in ways that visually mark them out their identity from others – sometimes in extreme ways, especially amongst the young, who are experiencing the tensions between their public and private selves especially strongly. The fashion for tattoos is in this light an attempt to wear your private self on your skin – to share it with the outside (which is maybe one subliminal reason why tattoos are always pixelled out on Korean television). The whole gender fluidity issue in the West can also be discussed in these terms: it’s about people struggling to fit their private selves comfortably within their public selves in a society where the public/private binary is no longer firmly established, where no one is quite sure where on begins and the other ends, or what constitutes one’s identity.

Another dimension relates to multiculturalism. When people began living together who look very different from each other, it was obvious that this visible sign of difference correlated to differences in the hidden private realm. Korea has no such diversity. More or less everyone in Korea is ethnically Korea. They have the same colour hair, the same colour eyes, the same colour skin. Of course, there are differences. Koreans are not clones. But compared to London, Seoul definitely looks mono-ethnic. This makes policing the private/public realms much easier. There are no visceral triggers signalling the ‘irruption’ of identity via the private into the public. Instead, one can go through one’s day without any strong awareness of one’s distinctly divergent status as part of a poly-ethnic society, and instead can comfortably assume one’s unity with others. This also means that it is much easier to consider oneself in terms of a public self – which is ‘public’ precisely because it is like all the other public selves – rather than, as in the West, constantly being reminded that the public realm is made up of private individuals.

*

While I was lying awake unable to sleep because of jet lag back here in Korea, and also suffering from a cold that I caught somewhere in London, it struck me that the willingness of Koreans to wear face masks is subliminally a collective re-instating of the public/private binary in the face of the threat to this boundary due to Westernization. By donning a mask one effaces to a considerable extent the external signs of one’s individuality – the private self visible to the outside world – and makes oneself part of an anonymous homogeneous group. As a Westerner, I find this tendency very unsettling, even ‘inhuman’.

It’s interesting that on Korean current affairs television programmes one often sees members of the public with their faces obfuscated, fogged, or pixelled out, to conform with privacy laws, or ‘portrait rights’, which mean you're not allowed to post or film other people's faces on media without explicit permission. The result can be really rather surreal or comical. Sometimes, it seems that every living thing on the screen is a mass of pulsing pixels. Or the tv cameraman is obliged to shoot at a weird angle so they don’t inadvertently get people in the frame and infringe their privacy.

I think in this context the face mask can be described as functioning as analogue fogging or pixelating. Of course, it is ostensibly intended to safeguard private and public health, but unintentionally, what happens is a radical delimiting within the public sphere of the visual attributes of the private. The mask has become a way of suppressing the expression of individual identity by serving as a wall between the private and the public realm.

The result is social conformity and stability. But I find it hard to believe this can be altogether healthy.

Image source:

North Korea’s Victory over Covid-19

So, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea did not collapse due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Why?

So, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea did not collapse due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This is what the excellent website 38 North said on August 15 :

‘Despite widespread concern that a COVID-19 outbreak in North Korea would be devastating, given the country’s weak health care system, limited access to medical equipment, supplies and medicines, and widespread malnutrition, Pyongyang appears to have stabilized the recent outbreak in record time with minimal deaths, at least according to the official government narrative. While North Korea seems to have avoided drastic outcomes this time around, its anti-epidemic efforts came at high economic and social costs, and the largely unvaccinated population remains a concern to global efforts to combat this virus. Building the country’s capacity to deal with epidemics and health crises should be part of a global health strategy to prepare for future pandemics.’ (1)

Of course, we are used to not taking anything North Korea says at face value. Officially, they say that on July 29, 2022, the number of what are called euphemistically ‘fever cases’ reached zero. Almost 20 percent of the population fell ill, but the number of deaths was only 74, a case-fatality rate of 0.0016 percent. As all the experts point out, this is impossible. The lowest country for case-fatalities is Bhutan at 0.035 percent. Other countries with vaccination rates above 80 percent, such as Singapore, South Korea and New Zealand, reported 0.1 percent.

But whatever the actual numbers, even the most hawkish critics of North Korea accept that the crisis was handled. The regime did not topple. Life (such as it is) goes on.

So, why? 38 North offers some answers:

‘North Korea’s health care system is founded primarily on preventative medicine, making disease monitoring and prevention the priority. As such, during the COVID-19 outbreak, local doctors and medical students were tasked with visiting 200-300 homes per day to facilitate disease surveillance.

Based on state media reporting about the pandemic responses, it appears that the North Korean government’s stewardship of the response to the outbreak has been effective and efficient. They declared a national emergency immediately after the first confirmed COVID-19 case, ordered a nationwide lockdown, and delivered medicine and food to houses while promoting the production of domestic medicine. State media has also reported the case numbers and provided medical information about COVID-19 daily.

With limited geographic mobility and domestic migration even before the pandemic, North Korean society is set up in a way that makes controlling the transmission of this airborne virus easier than in most countries. In short, North Korea was able to quickly stop community spread through aggressive public health measures, and as such, has not experienced a catastrophic situation. Furthermore, the first reported COVID-19 case was said to have been of the Omicron variant, which while more contagious, is less severe than the original virus or other variants.’

What this prognosis boils down is an interesting fact: the least ‘open’ society in the world proved to be one of the best at dealing with the pandemic, while the most ‘open’ societies proved the worst.

In his book Open. The Story of Human Progress (2020), Johan Norberg writes that ‘openness’ is inextricably tied to globalization: ‘Present day globalization is nothing but the extension of…. cooperation across borders, all over the world, making it possible for far more people than ever to make use o the ideas and work for others, no matter where they are on the planet. This has made the modern global economy possible, which has liberated almost 130,000 people from poverty every day for the last twenty-five years.’ Norberg also notes that ‘when China was most open it led the world in wealth, science and technology, but by shutting its ports and minds to the world five hundred years ago, the planet’s richest country soon became one of the poorest.’ Nowadays, however, China has sufficiently opened up to globalization to become prosperous again.

North Korea is an obvious example of what happens when a country is ‘closed.’ Interestingly, on this level it follows the policy of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897) whose isolation earned Korea the named ‘The Hermit Kingdom’, and also made it a ripe pickings for Japanese colonial ambition in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries. Japan, of course, did ‘open’ up – it was the first of the East Asian nations to do so, and the first to colonize another East Asian country (Korea in 1910) and to defeat a western power (in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05) . In this sense then, North Korea is a reversion to a former societal model, whereas South Korea, who has aggressively joined the ‘open’ global market, is following themodel first pioneered by its neighbor and former colonial master, Japan. It is obvious in pretty much all terms which of the Koreas chose the better path.

*

But the ‘openness’ of globalization is precisely what allowed the pandemic to happen. This is a fact that North Korea’s success highlights. The downside of ‘openness’ is porosity of borders. As Jared Diamond points out in his classic Guns, Germs, and Steel. The Fates of Human Societies (1997): ‘The rapid spread of microbes, and the rapid course of symptoms, mean that everybody in a local human population is quickly infected and soon thereafter is either dead or else recovered and immune. No one is left alive who could still be infected. But since the microbe can’t survive except in the bodies of living people the disease dies out, until a new crop of babies reaches the susceptible age – and until an infectious person arrives from the outside to start a new epidemic.’ (Emphasis added) The classic historical case of this viral invasion is the virtual annihilation of the indigenous peoples of north, central and south America by ‘white’ settlers who brought their infectious diseases with them – diseases for whom they had developed immunity but the indigenous people , having never been exposed to them, had not. Diamond gives several examples. Here’s one that is harrowing in its definitiveness: ‘In the winter of 1902 a dysentery epidemic brought by a sailor on the whaling ship Active killed 51 out of the 56 Sadlermiut Eskimos, a very isolated band of people living on Southampton Island in the Canadian Arctic.’

An ‘open’ society is bound to be prone to epidemics, while a ‘closed’ one is more likely to be able to control them. But it is also much more dangerously vulnerable if (indeed, when) the closed gate is breached. This vulnerability explains why a ‘closed’ society will desperately fight to keep the gate closed. But it also explains why they are doomed to fail.

Living in societies that value ‘openness’ is not just about markets, however. It’s also about ‘openness’ to worldviews, beliefs and behaviour, and this means a society will also be vulnerable to cultural ‘infection’. An ‘open’ society is perpetually being ‘infected’ by alien worldviews, and this inevitably causes tensions, and possibly conflicts. But as time goes by, the people of an ‘open’ society develop ‘immunity’ to these novel cultural pathogens. This is clearly what has happened as western societies have become more tolerantly multicultural. But the onslaught is continuous, and inevitably unsettling. Meanwhile, in a ’closed’ society like North Korea – in fact North Korea could be described as the archetype of a ‘closed’ society – cultural pathogens are not an immediate danger. They lie safely beyond the closed gate – in South Korea, America, Japan - but the dangers they potentially pose can be used to install fear in the populace.

Interestingly, the North Koreans claim that the Covid-19 virus entered their land via ‘alien objects’ found on a hillside. They elaborated by saying that these ‘objects’ came via balloons from Korea (the South Koreans have banned the sending of propaganda via balloons across the DMZ, but it still happens). Much more likely is that the disease entered via illegal trading with China.

In other words, total closure of a society is impossible. It always has been, as humans are hard-wired to trade. Where societies are concerned, there’s no such thing as totally water-tight barrel. They will always be leaky. Which is why an ‘open’ society is an inevitable advance on a ‘closed’ one. But this is especially true in an era of technologies that allow for ease and speed of travel. In earlier times, when people could only travel by foot, horse, horse and cart, or by sail across the oceans, being ’closed’ seemed a viable option. Today it obviously is not.

So, even though North Korea stamped put Covid-19 with remarkable success, it is surely still doomed.

Image source: https://www.ft.com/content/4f82c57b-fb10-4945-b6ab-df9445c57715

Masks….Yet Again.

I spent the summer in France, and it was quite a shock to suddenly be somewhere in which wearing facemasks was no longer mandatory in public places, as it still very much is in Korea. I am also back in the classroom teaching students face-to-face, or mask-to-mask. I am finding it a terribly demoralizing experience. The masks of my student make it difficult to recognize them, but even more awful, completely erases one of the most important markers through which I can receive signals of a student’s active engagement with my teaching – their mouths. This post incloves some more reflections on cultural difference as revealed through the protocols of wearing facemasks.

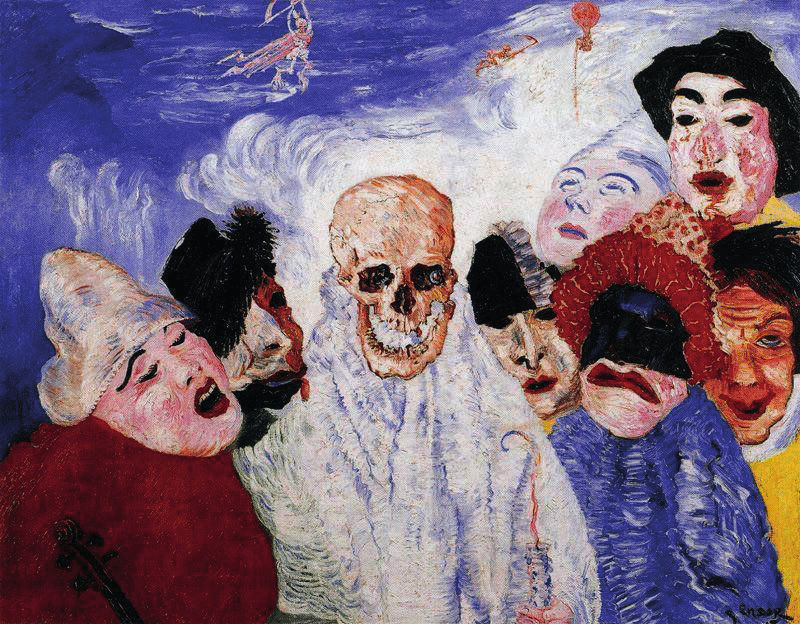

James Ensor, Death and the Masks (1897). Source: https://www.artforum.com/print/previews/201007/james-ensor-26245I apologize for once again writing about damn face-masks. But as I mentioned a couple of posts ago, I spent the summer in France, and it was quite a shock to suddenly be somewhere in which wearing face-masks was no longer mandatory in public places - as they still very much are in Korea. I am also back in the classroom teaching students face-to-face, or rather, mask-to-mask, and I’m finding it a terribly demoralizing experience. The mask makes it difficult to recognize my students, but even more awful, completely erases one of the most important markers through which I receive signals of their active engagement with my teaching: their mouths.

Inevitably, this has got me thinking about the face-mask again as a sign of cultural difference, and why it is that Korean society finds it so much less onerous to wear them than do westerners. Why are the latter willing to take more risks with their own and others’ well-being than Koreans? Why is the calculus of relative pros and cons so different? In particular, I have got thinking about the trade-off between public health safety assessed in terms of viral infectiousness and social solidarity, as exemplified by Korea, and public health safety assessed more (and mostly unconsciously, I think) in terms of psychological well-being, humaneness, and the values associated with sociality and freedom, as exemplified by the west.

By now, I’ve read several psychological and medical reports about face-masks. I’ve found that while the physical health benefits are pretty much agreed on there is less consensus concerning their potential psychological toll. Are children being permanently or even temporarily mentally affected in negative ways by having to wear masks? To what extent is people’s capacity for empathy being temporarily or permanently obstructed? Are we being turned into abnormal or even sociopathologically solipsistic automatons?

My classroom of masked students is bad enough, but it is hard to conjure up a more visually graphic image of psychological social alienation than a subway carriage of Koreans bent over their smartphones and wearing masks (see my post from May 24th, 2022 for another take on the effect of smartphones in such situations). It also seems an especially powerful image of baleful subjugation and conformity. I can’t help but see the combination of face-mask and smartphone as constituting a socially and politically useful way of pacifying people, and also without any obvious coercion, as they are ‘self-medicating’ by apparent choice. The passengers are tranquilizing themselves by drastically narrowing their potential interactions with the immediate environment.

This is, to be sure, an environment that possesses a great number of visual, aural, olfactory and tactile stimuli that are likely to make any half-normal person feel uncomfortable, bored, or downright threatened, and that are not in any stretch of the imagination attractive, pleasant or benign. The mask aids and abets the healthy quest for secure environmental buffering. It is an excellent means of hiding oneself from the gaze of a disagreeable world. I don’t just mean the gaze of other people, but more metaphorically, the ‘gaze’ of one’s surroundings - the call to us made by these surroundings. of spaces with which we are actively connected and with which we instinctively expect to be able to respond resonantly.

The face-mask is a way of ensuring that one remains distant, detached, and disengaged. But in the subway the masking of the face is combined with the lowering of the head and the directing of the gaze towards a small illuminated rectangular screen. As I have discussed in a previous past, this dramatically limits access to the expansiveness of the visual field which the human eye has evolved to see. It produces a kind of tunnel vision, and, as the term in popular usage implies, involves a narrowing and impoverishing of vision. But the smartphone makes this seemingly detrimental action alluring because it substitutes the unpredictable, threatening, ugly, actual surroundings for surroundings over which one has complete control, that via the magic of the Internet offer potentially resonant relationships to the world rather than alienating ones. This is a very attractive trade-off, and no wonder everyone is eager to make it. We transports ourselves from the disagreeable place where our bodies are located in real time and space to another space replete with much more appealing stimuli.

A subway system anywhere in the world is never going to be a very appealing and enlivening environment, especially in the rush-hour. It’s inherently awful, really. No one in their right mind would choose to be there. But of course, we all ride the subway because we need to get to work or want to meet our friends. Like so much of modern city life, the environment through which we habitually move is an inherently alienating one. Not so much a concrete jungle as a concrete desert. The casting down of the gaze and the focusing of attention on a small illuminated screen, plus the concealing of the nose and mouth behind a mask are therefore highly efficient ways of blocking or buffering contact with one’s immediate surroundings and achieving a relatively robust form of autonomy and control. But obviously, these benefits come at a dreadfully high price.

*

I used the word ‘buffering’ above in knowing reference to the writings of the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, who juxtaposes the terms ‘buffered’ self with ‘porous’ self in order to make a basic distinction between the modern and pre-modern conceptions of identity within European society. The ‘porous’ self is an earlier model of human relationship to the world that characterized Europe prior to the seventeenth century. What Taylor describes as the uniquely modern ‘secular’ world is precisely a world in which relationship are no longer founded on ‘porosity’ of self but on the benefits accrued from the bounded of ‘buffered’ relationship of the self to the world.

Here is what Taylor says about the latter in A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007) : “As a bounded self I can see the boundary as a buffer, such that things beyond don’t need to ‘get to me’, to use the contemporary expression….This self can see itself as invulnerable, as a matter of the meaning of things for it.’ (p.38) A ‘buffered’ mode of existence “can form the ambition of disengaging from whatever is beyond the boundary, and of giving its own autonomous order to its life. The absence of fear can not just be enjoyed, but seen as an opportunity for self-control or self-direction.” (38-9) Thus, the ‘buffered’ self is characterized by a stance of disengagement from the world which is adopted because it accrues a “sense of freedom, control, invulnerability, and hence dignity”(285). Taylor notes that much of the value associated with this ‘buffered’ disengagement from the world has derived from the way in which it mirrors on the level of personal existence “the most prestigious and impressive epistemic activity of modern civilization, vz., natural science” (p.285), that is to say, the rational or objective point of view.

By contrast, there is the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. Here, “the boundary between agents and forces is fuzzy……[T]he boundary between mind and world is porous” (39). The relationship to the world is also what Taylor calls “enchanted”, by which he means that because there is no firm boundary between self and world, one feels intimately affected by the world in ways that continuously open one up to uncontrollable an mysterious forces. There is no clear distinction between the subjective and the objective, the interior world and the exterior.

In his study, Taylor is limiting his analysis to the western world, but it seems to me that his concept of ‘porous’ and ‘buffered’ selves can be extended to global proportions (with obvious caveats). It seems especially interesting in relation to cultures that have experiences rapid modernization under the aegis of western ways of thinking, and therefore have evolved rapidly from societies based on the ‘porous’ self to ones based on the ‘buffered’ self.

So, back to the Seoul subway carriage. Is it too much to suggest that the uniform behaviour of the Korean passengers of all ages (except the very old, who are not accustomed to smartphones!) can at least in part be understood by recognizing that they are living in a culture that has metamorphosized from one dominated by the pre-modern ‘porous’ self to one increasingly dominated by the benefits accrued by being a bounded, disengaged ‘buffered’ self - a self that makes one a fully-fledged ‘modern’ person? But the speed of change means that the characteristics of the ‘porous’ and the ‘buffered’ self co-exist in unique ways in Korea. For example, the high level of conformity manifest in Korean society is a clear reflection of a core characteristic or the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. As Taylor writes of European culture: “Living in the enchanted, porous world of our ancestors was inherently living socially. It was not just that the spiritual forces which impinged on me often emanated from people around me……Much more fundamental, these forces impinged on us as a society, and were defended against by us as a society……So we’re all in this together.” (42) Taylor’s words made me think of the collective reaction within Korea to Covid-19, and how they contrast to the western response, which was far more based on a ‘buffered’ sense of self in which individual autonomy has priority of the social sense of all being “in this together.” As Taylor adds, as a result of the pressure to subordinate self to group, in a society ruled by a sense of the ‘porous’ self there will be a “great pressure towards orthodoxy.” (42) But in contrast to this impulse, one can also very clearly observe in modern-day Korea other forces that derive from the adoption of the new bounded, ‘buffered’ sense of self, which prioritizes disengagement as a source of self-efficacy. As a result, , in the Seoul subway carriage we find the melding within the same person of characteristics of ‘porosity’ and of ‘buffering’ in relation to the self, of collective behaviour and disengagement.

Has the speed of social transformation been fundamentally traumatizing for Koreans? Are the visible exterior signs (the persistent mask, the obsessive zoning in on the cellphone screen) the manifested signs of an interior mental state that is, in a sense, a kind of mental and social derangement?

“Welcome to the Wild West”

HAPPY NEW LUNAR YEAR! It’s the Year of the Tiger.

This is one of my Book-Paintings. You can see lots more on my artist’s website: www.simonmorley.com

I’ve been silent for a while on this blog after a period when I focused exclusively on a series of posts celebrating the publication of my book ‘By Any Other Name. A Cultural History of the Rose’ because over Christmas and New Year I went back to my homeland, the United Kingdom, and since then (I’m now back in Korea) I’ve been mulling over my rather disturbed and disturbing experience over there. I am referring to the impact of Covid-19, and especially to the culture-shock I felt when experiencing the different responses of people in the UK compared to here in Korea. My book, by the way, is doing well. It’s had some good reviews. The Times Literary Supplement said: “Fascinating material, surveyed with relish and acumen.”

But I want now to get back to more general blogging, and especially to think about the complexities and paradoxes of East-West cultural dialogue once again.

I said I wouldn’t write about face-masks again, but here I go again.

On my second or third night in London, while I lay awake with jetlag, a voice in my head seemed to say: “Welcome the Wild West!” Yes. That’s what it felt like being in the UK. Compared to Korea, things seemed very anarchic, especially in relation to Covid-19 and the threat posed by the new Omicron variant. I was amazed to find that people considered that their responses to the requests for compliance regarding the pandemic - to wear face-mask on public transport or to get vaccinated - were to see them as personal choices rather than social duties. Now, there are many ways of explaining this. One is related to specific political conditions. In the UK (and I think more broadly in the West in general) there seems to be a fundamental loss of trust in the state. This distrust means that people do not believe in what the institutions vested with authority say. They see them as, for example, a patriarchal plot or a way to make more money for the ‘one percent.’ This loss of trust is pervasive. It extends to all levels of social life, from personal relationship to political leadership. The causes are obviously complex, but I think have much to do with a basic flaw in individualistic conception of the self, or in what has been called ‘possessive individualism.’

Now, I know it’s risky making hard-and-fast distinctions between cultures, and I am aware that there is no such thing as fixed cultural identities. However, there is plentiful evidence provided by the responses to the pandemic that confirm that Western societies function very differently from East Asian. Let me try to suggest some ways to understand these differences – albeit differences proposed by Westerners.

The Canadian social psychologist Stephen Heine, for example, discusses how concepts of selfhood are determined by interactions with the cultural environment and ossify into recursive cultural orientations. He describes an East Asian cultural bias towards what he calls the ‘interdependent self’, where individuals are understood to be connected to each other via a network of relationships. This Heine contrasts to the Western model of the ‘autonomous self’, where selfhood is generated in contrast to others. As Heine notes: “In general, across a wide variety of paradigms, there is converging evidence that East Asians view ingroup members as an extension of their selves while maintaining distance from outgroup members. North Americans show a tendency to view themselves as distinct from all other selves, regardless of their relationships to the individual.” The individualistic West confronts the collectivist East. “The resultant self-concept that will emerge from participating in highly individualized North American culture will differ importantly from the self-concept that results from the participation in the Confucian interdependence of East Asian culture”, writes Heine.

The American social psychologist Richard E. Nisbett argues that in the West consciousness is construed as non-corporeal, detached and autonomous. ‘”For Westerners,” writes Nisbett, “it is the self who does the acting; for Easterners, action is something that is undertaken in concert with others or that is the consequence of the self operating in a field of forces.” As he continues: “to the Asian the world is a complex place composed of continuous substances, understood in terms of the whole rather than in terms of the parts, and subject more to collective than to personal control.” In this world-view there is an intrinsic overlap between self and world.

Meanwhile, for the Westerner, writes Nesbitt, “the world is a relatively simple place, composed of discrete objects that can be understood without undue attention to context, and highly subject to personal control”. The ‘analytic thought’ prioritized in the West follows patterns organized through visual segregation. It dissects the world “into a limited number of discrete objects having particular attributes that can be categorized in clear ways”. Nisbett details research that shows that Japanese participants in his experiments are more attentive to the whole perceptual field than Americans, who are more drawn to individual foci of attention.

This divergence is also paralleled in the structure of language. East Asian languages like Korean are highly contextual; words typically have multiple meanings. The absence of personal pronouns in Korean adds to its inherent ambiguity, and foregrounds the role played by context in determining meaning. Western languages, in contrast, are more context-free and preoccupied with focal objects as opposed to context. The ‘holistic thought’ characteristic of East Asia, “responds to a much wider array of objects and their relations, and [...] makes fewer sharp distinctions among attributes or categories, [and so] is less well suited to linguistic representation.” Awareness of process predominates over the search for essences or fixed and finite forms. It is therefore non-binary, promoting a ‘both/and’ approach to problem solving.

One way of observing these different world-views at work is to think about how ‘mind’ – the part of the self that thinks, reasons, feels and remembers – is conceptualized. Most Westerners will point to their cerebrum when asked to locate the physical location of this elusive entity, while most East Asians will point to the region of their heart. Etymologically, the meanings of the English word ‘mind’ cluster around the act of remembering and memory, while the French word ‘esprit’ suggests another etymology that brings meaning closer to spirit, energy or liveliness. But s the West developed a more thoroughgoing dualistic view of consciousness within modern rational thought, ‘mind’ has been opposed to ‘body’, which explains why Westerners point where they do. In contrast, the Chinese written character translated into English as ‘mind’ is composed from the ideogram for heart. Since ancient times the heart was understood to be ithe mind’s location, and so the two are interchangeable and inextricable.

Both concepts of ‘mind’ are congruent with the contrasting ‘analytic’ and ‘holistic’ world-views from which they arise. In the former, the self is detached from a world that is viewed as static and compartmentalized, while in the latter, the self is corporeally immersed in the flow of life.

The clear benefits to be gained from both paradigms explain their cultural recursiveness. The Western model has the following broad characteristics: it fosters an intellectual attitude preoccupied with mental activity and values, differentiating intellect and psychology from the somatic dimension. Emphasis is placed on analytic thought, which means experiences are processed by being abstracted, and divided into elemental parts or basic principles. The discursive mode of thinking is valued, in which thoughts proceed to a conclusion through deductive logic, reasoning and objective analysis rather than emotion and intuition, promoting a cognitive style uninfluenced by personal feelings or opinions when considering and representing facts. It thereby ensures grounds for publicly verifiable objective facts freed from affect. This world-view fosters self-consciousness and reflectiveness, and generates the idea of a transcendent realm of pure forms or non-material entities, of a God who is separated from the natural world.

The East Asian world-view, on the other hand, offers the self a greater sense of being united with a trans-personal whole. It fosters awareness of complementarity and intimate connectedness. Furthermore, it is somatically oriented, seeing the self as immersed in a living, bodily and participatory context. Ontologically, there is the notion that the self exists in the midst of things rather than externally. More attention is paid to affect – to pathos as well as logos – as a component of knowledge, and this leads to the acknowledgement of the value of non-verbal understanding. Some important knowledge is construed as essentially ‘esoteric’ or ‘dark’, rather than bright and clear. Epistemologically, this means non-duality or monism. Distinctions between ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ therefore have little value. Metaphysically, it fosters the idea of an immanent spirituality, occurring in the here and now.

Because of the East Asian bias, the self within this cultural matrix tends to be uncomfortable with the analytically cognitive, and with abstractions. As a result, there is an absence of individual, reflective, affect-free critical thought. Because much cognition is understood to happen beyond the scope of language, within the discursive domain there is a tendency to depend on shared tacit knowledge that remains unchallenged and under-articulated subjectively. This means a proclivity towards reliance on the consensus view and shared viewpoint, rather than on individualized and potentially dissenting expression.

A detrimental consequence of the Western recursive paradigms is that the atomization of selfhood into individualistic ‘autonomous’ units isolates the self from the wider community, fostering potential antagonism between the interests of the self and the social realm. When thinking, Westerners tend over-value the medium of verbal language, believing that if they put thoughts and feelings into words, and then act upon them, they are in control. Failure to realize these criteria, which often appear to the self as a critical and antagonistic relationship to the status quo, signifies a lack and a loss of mastery.

One can see how these fundamental differences in the social construction of consciousness impact on the requirement to wear face-masks or to be vaccinated. Westerners are inherently more likely to consider these issues in terms of individual integrity rather than group intimacy, that is, they will consider the mandates coming from government and underwritten by scientific evidence, which is reinforced by social pressures, primarily in terms of a personal demand to comply, as a request to subordinate one’s preeminent goal of maintaining a zone of personal freedom to an essentially threatening outside. In Korea, by contrast, people on the whole do not see the mandates as impinging in any significant way upon their personal integrity, which is constructed more permeably in relation to others within society.

Which reaction is more efficacious in these worrying circumstances? Almost certainly the Korean. But I have to say that after my initial shock on first being back in the UK I ended up feeling relieved to be in a country where individualism is so stridently policed by individuals. Now I’m back in Korea I can see that the compliant conformity certainly brings a sense of security, but, at least to this individualistic Westerner, it can feel unbearably dispiriting.

References::

Steven J Heine, “Self as Cultural Product: An Examination of East Asian and North American Selves”, Journal of Personality, 69 (6), 2001, pp881–906. http://www 2.psych.ubc.ca/∼heine/ docs/2001asianself.pdf.

Thomas P. Kasulis, Intimacy or Integrity: Philosophy and Cultural Difference (Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. 2002)

Richard E. Nisbett, The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently...and Why (New York: Free Press. 2003)

New Year’s Eve at the DMZ

Here’s what the view looked like across the Han estuary, looking towards North Korea, as the sun set on New Year’s eve, 2020. Over the other side they claim there is no Covid-19. It seems it takes the most authoritarian regime on the planet to beat this damned virus, and the most individualistic to succumb most abjectly to it.

Weird, eh?

Anyway. Happy New Year!

Korean Protestantism and the Virus

Disinfecting a Protestant Church, Seoul.

The news from South Korea concerning the new spike in Covid-19 cases, which can be traced to a Protestant church in Seoul, called Sarang Jeil, comes just five months after another church, Shincheonji, in Daegu, propelled South Korea to unenviable pole position in the pandemic. This coincidence compels me to write something about Christianity in South Korea.

It is probably surprising to most people to learn that South Korea is fast becoming a majority Christian country. When I arrived here for the first time in 2008, I thought Koreans were mostly Buddhist. Some are, but not many. Here are the current statistics: the majority of the population, 51%, claim to be irreligious. Buddhists amount to only 15.5%. Of the Christian denominations, 19.7% are Protestant (mostly Presbyterians, Like Sarang Jeil, or Methodists), and 7.9% are Roman Catholics (like my wife, though lapsed). Shincheonji, although derived in part from Christian beliefs, is considered a cult, or more fairly, a ‘new religion’. There are many in Korea. The most well-known is the Unification Church, or the Moonies, which was founded in South Korea and is now a worldwide movement, with followers especially in the United States. Also, the category ‘irreligious’ doesn’t mean the same thing as it does in the UK, where in fact, only 29.7% claims to be irreligious. Behind the smoke screen of irreligion a good deal of religious activity is going on in South Korea.

Two other important religious infleunces need to be considered. The first is shamanism. This predates all the other religions currently characterizing the syncretistic mix of modern South Korea, and although officially frowned upon, and not an official religious creed, shamanism is still a very significant part of Korea’s deep spiritual consciousness (more on shamanism in a future blog). The other important ‘religion’ is Confucianism’, although for many, Confucianism isn’t so much a religion as an ethical code because it gives no place to a supernatural dimension – which is why so many claim to be ‘irreligious’. However, Confucianism is definitely a religion in the broader sense, as binding the secular dimension to a sacred one, and the sooner we Westerners recognize this fact the sooner we will grasp what it is that underlies much of what happens in East Asian societies, not just Korea – North and South – but also China. I will discuss Shamanism and Confucianism in later posts.

A church like Sarang Jeil is inspired by American-style evangelical Protestantism. I was baptized a Presbyterian – the Church of Scotland – by Sarang Jeil-style Presbyterianism has very little in common with that austere and staid denomination. First of all, it’s far more evangelical and fundamentalist. But a little historical context is first necessary in order to better understand Korean Protestantism.

Koreans identify Protestantism with the heroic struggle for independence from Japanese colonialism, because many of their leaders were Christian, and so they also identify it with proud South Korean nationalism, especially in the face of the anti-religious fevrour of North Korea.. Another key aspect of Korean Protestantism is its relative rejection of the acutely patriarchal system that underlies traditional Korean culture largely as a result of the influence of Confucianism. Women find Protestantism more attractive than both Confucianism and Korean-style Buddhism – which is similar to Zen (more on this, too, in later post).

Koreans also identify evangelical Protestantism with something else that chimes with their cultural background – a powerfully emotional, irrational faith based tied to the infallibility of a charismatic leader. This chimes with an instinctual suspicion Koreans have for the official leadership, who they see has inevitably corrupt and will betray them. During the Joseon Dynasty, it was commonly believed by the peasantry that the ruling elite inevitably abandoned them to fend for themselves when enemies invaded. But while suspicion of the ruler is deep, the desire for leadership is even deeper, and inclines Koreans to ally themselves with anyone who claims to speak for their special interests.

Korean Protestantism it also charismatic. This links Sarang Jeil to Koreans’ subterranean bond with shamanism. The ecstatic ‘trance’ like dimensions central to shamanism, which are deeply ingrained in Korean culture, seem to have found a new and more acceptable outlet within this kind of Protestantism. Koreans associate shamanism with the past, with the failed Korea of ‘Oriental’ culture, and Protestantism is allied with the positive future. Above all, Koreans identify Protestantism with a preferable affirmative model of the future, which is closely allied with the embrace of neoliberal capitalism, adoration and emulation of the United States, and of Westernization in general.

Some of the Korean Protestant churches are huge. Sarang jeil is a mega-church. Its congregation numbers 4,000. There are several of a similar size in South Korea. Each one owes allegiance not so much to a general governing body but to a charismatic pastor. In this case, the leader is the now widely vilified Pastor Jeon Kwang-hoon, who is also the incumbent president of the conservative Christian Council of Korea. Jeon is a vocal critic of the present liberal President of South Korea, Moon Jae In. So this crisis also has a political dimension.

Pastor Jeon Kwang-hoon after he was diagnosed with Covid-19. As you can imagine, when this photo was published in the Press, Jeon became an instant pariah.

Jeon’s defiant, non-conformist, behaviour is a reminder of the roots of Protestantism in protest, in the refusal to adhere to the laws of a society where the believers see the hand of Satan at work. Jeon encouraged his congregation to defy the government ban on church services due to Covid-19, and organized rallies in Seoul to protest against the current government despite their ban too. But he had been organizing rallies for months before the pandemic began. So the current Korean spike is linked to Korean politics, another instant of the more general corruption of the struggle against the pandemic by sectarianism worldwide.

In the mental universe of these Korean Protestants, the world is coloured in stark black and white – evil against good, with them, obviously, on the side of the good. Jeon also assured his followers that God would protect them from Covid-19. Now hundred have the virus, including Jeon himself. But we can be very certain that there will be no mea culpa, or not one in which Jeon or his followers admit that God didn’t protect them, after all. Rather, they will come up with some other explanation – however rationally absurd. Remember the claim made by the woman of the Shincheonji church, who said that Satan was jealous of her church’s success, and this is why the virus struck them. It is commonly known among psychologists who study cults and other closely knit groups whose bond is strengthened by a sense of righteous opposition and perceived persecution, that cognitive dissonance leads to a re-affirmation of belief in the face of overwhelming challenges.

So why did Covid-19 profit from Protestants? I suppose the broadest answer is to say that this kind of Protestantism is a faith that is overwhelming based on the ‘heart’ rather than the ‘head’. On the role of intuition, instinct, emotion, impulse, subjective experience, loss of individual ontological boundaries through immersion in the collective, joined with a concomitantly child-like belief in the infallibility of the chosen leader. This belief system excessively relies on fast and easy cognitive processes which are very susceptible to bias, what the psychologist Daniel Kahneman in his classic Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) dubs System 1 thinking. This kind of cognition is notoriously prone to poor decision-making and excessive reliance on top down group influences. What Kahneman dubs System 2 thinking, by contrast, is slow and requires conscious effort. But as a result, it is much more resistant to cognitive biases.

When a religion massively over-emphasises System 1 it is likely, sooner or later, to cause major societal problems, especially during something like a pandemic. The fact that the evangelical churches in the United States have not also been hotbeds of the virus is interesting, however. Perhaps the reason is political. While in the US the evangelicals have the president they want, in South Korea they do not. As a result, their willingness to follow orders differs. Although, what exactly President Trump’s ‘orders’ have been is rather difficult to ascertain. But it does seem that American evangelical mega-churches, are not, so far, major Covid-19 hotbeds.

My last blog entry mentioning face-masks

The face-mask makes what is already de-humanized behaviour a step more explicit.

What we are going through now may be a temporary expedient, or it may be the new shape of daily life. We shouldn’t be too surprised if it proves to be the latter, because we have already accepted as ‘normal’ much of what we, and the official commentators on the pandemic, are pretending are anomalies: De-humanization.

Responses to the Covid-19 threat require the temporary loss of many of the things which still make life bearable, makes it human – physical contact, the arts and entertainment, social mobility. But the responses to the virus are, in this sense, caricatures of what is already happening, and like all caricatures, they help us see salient aspects of our society that we overlook or ignore. The pandemic has caused a gestalt shift, and what was the unnoticed background has become the focal ‘figure.’

The face-mask is an especially explicit signifier of dehumanization, making manifest what has been latent (I promise this is my last post to mention face-masks!). A mask de-personalizes, and robs us of a basic locus of expressiveness - the mouth - in such an obvious fashion. So perhaps now we will recognize that it is only the new tip of the iceberg of de-humanization.

A supermarket or shopping mall is already a horribly de-humanizing place, but now that everyone is by law obliged to wear masks (in Korea, anyway, but I guarantee, also very soon in a supermarket or shopping-mall near you) it becomes much more obvious. Or at least for as long as the face-mask is novel. But soon, it will have become as unremarkable as all the other de-humanizing aspects of modern shopping which we now accept as just part-and-parcel of ‘normal’, ‘convenient’ daily life.

Another example. The way in which the pandemic has forced more and more social interactions on-line. This form of communication was already de-humanized, in that it largely subtracts the body from social interaction. But now that a meeting between friends, a meeting of work colleagues, or a school or university class, must take place via Zoom or some such platform we can more readily recognize the blatant way in which the digital media impoverish human communication.

What I have said assumes, of course, that there is a prior concept of what it means to be healthily ‘human.’ Where does this concept come from? Some would say it is an ideological construct. But I am increasingly convinced that this is nonsense. We all instinctively know what it means to be ‘human’. The problem is we live in a society that, for reasons much too complicated to consider here, seems hell-bent on an agenda of de-humanization.

But I don’t think we can cast this process in terms of conflict theory - of the oppressor and oppressed. Bizarre as it may seem, everyone get de-humanized in their own way. Perhaps the best way to describe the dynamics of de-humanization is to say that they are semi-autonomous. De-humanization has taken on a life of its own independent of any particular human agent. Maybe it’s a dehumanization ‘memeplex’, to use the terms of Richard Dawkins. If so, then Covid-19 is now part of its survival strategy.

More on Roses

A Dog Rose as painted by Redouté

In late April 2020, while I was writing my current book, By Any Other Name. A Cultural History of the Rose, to be published by Oneworld, it was announced that a local municipal authority in Japan were snipping off thousands of rosebuds in a popular public park in a desperate attempt to stop people congregating there to admire the blossoms when they arrived in early May, thereby encouraging the spread of Covid-19. Thoughts of a team of grim Japanese gardeners frantically decapitating rosebuds, brought to mind Morticia (played by Angelica Huston) in the movie The Addams Family (1991) who is shown snipping off all the blood-red flowers of a climbing rose with gleeful diligence.

One of the sad implications of this news story for me was how it vividly exposed humanity’s cruelty, unleashed against nature but also against itself, and enacted, apparently, for the collective or greater good - in order to protect people. But one has to ask what kind of life is it we are protecting that demands such a bizarre act? Fortunately, however, these panic measures were newsworthy mainly because of their extreme and perverse nature. But nevertheless, we should not see them as wholly exceptional, but as the exaggerated expression of the pervasive crisis whose end is far from in sight.

Why a book about roses? In a past post I explained how I first became fascinated by the rose as a plant and a symbol. In this one, I’ll talk a bit more about the theme, as it now presents itself to me.

The iconic American ‘Hippy’ band, Grateful Dead had a thing about roses. The cover of their second album, released in 1971, shows a drawing of a skull garlanded with red roses. Here it is:

The image was lifted and adapted from an illustration in an edition of the Sufi classic, Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The Sufi’s also had a thing about roses. As Grateful Dead band member Robert Hunter puts it: ' I've got this one spirit that's laying roses on me. Roses, roses, can't get enough of those bloody roses. The rose is the most prominent image in the human brain, as to delicacy, beauty, short-livedness, thorniness. It's a whole. There is no better allegory for, dare I say it, life, than roses."

So there’s the reason for a book on the rose. It gives me a chance to talks about ‘dare I say it, life’. This is from the beginning of the Introduction to my book (as it stands now):

Man hands on misery to man’, writes the English poet Philip Larkin with his characteristically stoic resignation. But man also hands on pleasure, love, passion, beauty, compassion, enchantment and hope, and, to these propitious ends, flowers have proven very useful and ubiquitous allies for thousands of years. We manipulate them without fear to construct pleasing, consoling and rejuvenating material environments and mental pictures. But of all the flowers, it is the rose that has been most often coopted to ‘whisper of peace, and truth, and friendliness unquell’d’, as another English poet, John Keats, puts it. The rose has helped to generate atmospheres conducive to the intimacies of the heart. It has provided a beautiful material form for the tenor, the meaning, sense, and content of the tenderer dimensions of our lives. As a gift, an offering, a resonant symbol, a focus of aesthetic attention, a medicine, a distilled oil, a perfume, a culinary ingredient, and as a plant lovingly cared for and cultivated, the rose has participated in social transactions that help establish, nurture, and sometimes end relationships between the living, the living and the dead, the divine and the everyday, the human and the non-human. Above all, the rose has served as one of the most enduring and pervasive images of a benign human future: a promise of happiness.

Today, the rose is probably the world’s favourite flower, and it is effectively binding together people of very different social backgrounds and positions, and historically and geographically distant cultures. It is no exaggeration to say that in the Western world, roses may even be one of the very first things a new born baby sees, as a bouquet of roses is such a common gift for new mothers. Subsequently, roses will enter this human’s life in many physical guises - organic, painted, sartorial, aromatic, imaginary. In fact, when you come to think of it, roses are likely to be present at all the most important moments in your life: births, birthdays, courtships, intimate dinners, marriages, anniversaries, Valentine’s Day, funerals.

The United States of America adopted the rose as its national flower quite recently, in 1986 during the Reagan era, when a powerful pro-rose lobby won out against the botanical competition, which included the marigold, dogwood, carnation, and sunflower. The statement supporting the advocacy, says much about the ubiquity of the rose within Western (and Westernized) culture:

‘They grow in every state, including Alaska and Hawaii.

Fossils show they have been native of America for millions years.

The only flower recognized by virtually every American is the Rose.

The name is easy to say and recognizable in all western languages.

It is one of the few flowers in bloom from spring until frost.

It has exquisite colours, aesthetic form, and a delightful fragrance.

Growth is versatile, from miniatures a few inches high to extensive climbers.

Roses mature quickly and live long.

They add value to property at minimal expense.

The range of varieties is such that there are roses to suit everyone.

As no other flower, the rose carries its own message symbolizing love, respect, and courage.’

Writing about the ‘queen of flowers’ hasn’t been easy while the world as we know it convulses in collective pain and uncertainty. And hopefully, the rose will remain for our children and their children, and their children’s children, a promise of happiness.

A Dubious Sense of Security

Who wins in the war on the virus?

This photograph was taken this morning from my home’s rooftop. The mountains in the distance are in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea – North Korea. Normally, the mountains are far more hazy, but thanks to heavy rain and Covid-19, I can see their craggy details more clearly than I ever have. Why thanks to Covid-19? Because the pandemic has lowered pollution levels; usually a large proportion of pollution drifts across the Yellow Sea from China to smother the peninsula.

Up north, beyond the DMZ which lies between me and those mountains, the leadership claims to have completely won the battle against the virus. Of course, we can treat this claim with skepticism. But let’s for the moment take it at face value, and put it in a broader context. This means that the most successful nation on earth at eradicating the threat of Covid-19 is also the most oppressive nation on earth.

In fact, if you think about it, the more authoritarian the nation is, the better it seems to have coped with the crisis (again, assuming the truth of the claims). This is because in these societies, the individual must routinely sacrifice what to Westerners seems like an unacceptable portion of their liberty in order to further what they are told is the common good. And which nations have fared worst in the battle against Covid-19? Those with a more individualistic culture, and especially those who have elected populist leaders, such as the United States, Brazil, and the United Kingdom, who make a point of espousing individualism at the expense of the collective.

What lessons can we learn from this striking contrast? One is that, at a deeper level of significance, this pandemic isn’t about the existential threat posed by a virus, but about how to achieve a sense of security, and about how to define ‘security’. What does ‘security’ mean, what value does it have for human beings, and how much are they willing to pay for it? After all, viruses are nothing new. They are an inherent part of human existence, and we literally live with them inside us, as well as outside. What Covid-19 has exposed is not so much our vulnerability to viruses or our dangerous unsettling of the ecosystem but the urgency of the perennial problem of existential and communal security. Or, more accurately, it has drawn attention to the urgency of the problem of how to achieve a credible sense of security, which isn’t the same thing as ‘security’ per se. Having the ‘sense’ that I am secure is a state of mind, and not necessarily a material condition or existential fact. But if I believe I am secure, then I will feel secure. There has been a lot of talk about ‘the normal’ and ‘the new normal’. What this means in this context is ‘the secure’ and the ‘new secure’.

Real, genuine, existential security can only be based on a shared unity of benevolent purpose, which has the effect of collectively shouldering awareness of the inevitability of insecurity, rather than trying to conceal it. This, alas, is totally unachievable within complex societies. But actually, one might call it generally utopian, in that it seems probable that humanity has never achieved such a refined level of social integration. But we are still capable of imagining it. In the meantime, a sense of security has become increasingly premised on another utopian dream: the irradiation of insecurity, or the perpetuity of security. Enter religion, with its offer of eternal life (read: eternal security). As I suggested in a previous post, this search for absolute security originates in childhood vulnerabilities, and fantasies of parental omnipotence. It makes us very susceptible to the rhetoric of infallibility, something that tricksters, con-artists, charismatic visionaries, and politicians, profit from. But in the context of my present argument, the key point is that the feeling of security is a state of mind, not a reality. Total security is a figment. A fantasy . But that doesn’t mean the notion of ‘security’ hasn’t got real, compelling, influence over human life. In fact, it’s what has driven us towards the endorsement of an increasing dehumanized society.

If we look at history, we can see that the sense of security is relative. Compared to today’s society, the level of rampant insecurity of a typical peasant in the Middle Ages might, objectively speaking, seem far far higher. But thanks to his religious faith, this peasant was actually likely to have had a sense of security that surpasses that of many people today. In other words, a sense of security is not linked like cause and effect, but is relative, and determined by specific priorities. The medieval peasant’s physical life is likely to have been ‘nasty, brutish, and short’, but his faith guaranteed him eternal life in heaven, and this guarantee, in turn, made his existential life feel more secure.

In this sense, security is determined by individual and societal visions of the future. A positive vision of the future will make the present feel more secure, while the absence of such affirmation, will make people more pessimistic. So a sense of personal and communal security is closely bound up with a society’s capacity to forge and maintain a credibly positive image of the future. This is precisely one of the things that the pandemic has brought to attention: the vulnerability of our image of the future. I will return to this problem in a future post, and return now to the lessons of the pandemic for our understanding of security.

The sources of our insecurity come and go, and very quickly become normalized and cease to evince fear, or an active sense of insecurity. The Atomic bomb massively increased feelings of insecurity within modern society, but within a generation it had become part of what is deemed ‘normal’ - that is credibly ‘secure’ - society. Sources of insecurity function like gestalts. They rise out of the undifferentiated ground of general impermanence to become foci of attention, then slip back into the ground. Or they suddenly land in our perceptual field and become foci of attention, but then, all going well, are more or less rapidly consigned to the unnoticed background. Indeed, we could say that a sense of security is dependent on consigning sources of fear to the background or periphery, where they will be unnoticed, but have not actually disappeared. Any ‘normal’ society is therefore characterized by a process in which sources of insecurity are ferried from focal attention to unnoticed background. But they do not disappear. Rather fear is transmuted into dread and anxiety.

A vital purpose of any national leadership is to supply a sense of security. Even a despotic one must at least guarantee security for its supporters and enforcers. But, as Marx emphasized, it is also usually politic to provide or sanction an ‘opium’ for the masses, just to be on the safe side. In the modern state, democratic or not, whoever is in control must make a good proportion of the people feel secure in the face of manifest insecurity. They do this by acting as guarantors of security through deflecting attention away from intractable sources of insecurity – nuclear war, pollution, climate change, random violence - and focusing attention instead on more tractable ones – terrorism, Covid-19. They know from studying history that insofar as security is the highest human priority, that the members of the society over which they rule will sacrifice a good deal of their freedom to possess a sense of security, and will thank their leaders with compliant support.

Any ruler is in the business of delivering states of mind not existential truths, and they need to conjure up the right ones. But in truth, the best any ruler can do is to transmute a dangerously destabilizing, fear-inducing, reality into a more socially manageable anxiety-inducing reality. All human life is, as Heidegger argued, lived in an atmosphere of anxiety, which is fear that has been dematerialized or de-focused. The security we are being offered is therefore not the absence of insecurity, but rather an acceptable level of insecurity. The job of a benevolent ruler is to guarantee this level remains more or less stable, while that of a malevolent ruler is to manipulate insecurity in order to maintain and profit from the increasing opportunities for social control and domination it will provide.

So one thing the pandemic is bringing to the fore is the price people are willing to pay for maintaining their illusory sense of personal and collective security. Quite a high price, so it seems. The pandemic is forcing nation states to re-calibrate the grounds upon which to establish for their citizens a credible sense of security. They are doing this in the time honoured manner : by extending their control over their citizens. And the reason their citizens are so willingly giving up their freedoms is because they have been conditioned to believe that the state controls security, whereas what is really happening to that the ruling elite is using the primordial need for security to extend its control over their lives.

*

Another lesson to be learned from the pandemic is that the form of a nation’s leadership is important in determining how a society can act collectively, but also, that whatever the ideology being espoused, the common goal is always the panacea of security. But the pandemic has starkly revealed the extent to which collective action to achieve security, when organized within a rigid and oppressive hierarchical system, is much more successful when compared to a system in which collective action is decentralized, local, and driven more by individual initiatives. By ‘successful’, I mean in relation to its capacity to effectively cultivate the belief among members of its society that they are secure.

The more totalistic a state, the more efficient it is at guaranteeing a clearly defined sense of security. This is because the totalistic state has the monopoly on security, and defines what it is, who will be granted it, and what will happen to those who do not conform to the regulations imposed to ensure the consolidation of this fabrication called ‘security’. China and North Korea claim to have successfully protected their peoples from the virus through strictly policing them. A sense of security is granted and achieved through the measures initiated by the state to ensure the limiting of the spread of the virus. But it is success gained at the price of strict conformity imposed through physical and psychological threat. The techniques used to fight the virus are, however, merely extensions of the range of routine techniques used to maintain a sense of security in ‘normal’ times in China and North Korea. In other words, security from the virus has been achieved through a concomitant heightening of awareness of the level of state induced personal insecurity that will ensue if obedience isn’t forthcoming. The state offers a sense of security by effectively monopolizing and deploying the fear that the security it establishes is ostensibly intended to allay.

The state removes security in order to guarantee security. It monopolizes security and its absence. This individual and collective conformity is ensured through the establishment of a dual regime. First, through systematic state-controlled indoctrination - ‘brain-washing’ - and second, through state-controlled surveillance. State-controlled indoctrination, or socialization, ensures a high-level of conformity, which surveillance helps to police and enforce. So the totalistic state’s monopoly on security is built on its monopoly on violence. Lock-down or else!

Ultimately, the pandemic in China and North Korea has been ‘defeated’ through the willingness and ability of the leadership to use insecurity – on the one hand in the shape of fear of the virus, and on the other in the shape of the state apparatus of control and repression – so as to ensure the continuing establishment of an illusory sense of security. The major difference between China and North Korea is that China’s regime relies on strict state controlled indoctrination supported by forms of surveillance that are increasingly accomplished, and exponentially extended and more efficient, via digital media. North Korea still relies on the old ‘analogue’ methods – that is, almost hegemonic state controlled indoctrination via the pre-digital media (print, radio, tv, cultural entertainment), combined with the old surveillance techniques of the neighbour’s spying eyes and ears, backed up by the punitive threat of a boot in the face.

Both China and North Korea have discovered that the danger of a pandemic can lead profitably to an increase in the state’s power to control the lives of its citizens, and that its people will accept the further invasions of their lives if it there is the caveat that this is necessary in order to guarantee the feeling of being secure (although it has to be said that imagining where this extension of control has infiltrated North Korean society is difficult, as the state already has such a total monopoly on security).

The question then is , to what extent is North Korea exemplary? In other words, is this level of social control actually more acceptable and potentially exportable elsewhere than we imagined? George Orwell certainly thought it was.

Meanwhile, in the United States, Brazil, and the United Kingdom a different leadership model and supporting ideology exists at the apex of a more amorphous social structure. Here, it is said that the state’s obligation to achieve a sense of security for its citizens must be counterbalanced by the promotion of the idea that individual freedom is sacrosanct. This concession to individual freedom inevitably jeopardizes the ability of the state to achieve a monopoly on the sense of personal and collective security. The underlying assertion is that security must to a certain extent be sacrificed in order to protect personal freedom and ensure economic stability. This reflects the self-image of a culture within which the ideology of individualism requires that security be defined in relation to personal separateness and autonomy. Security for the individual trumps security for the group or collective.