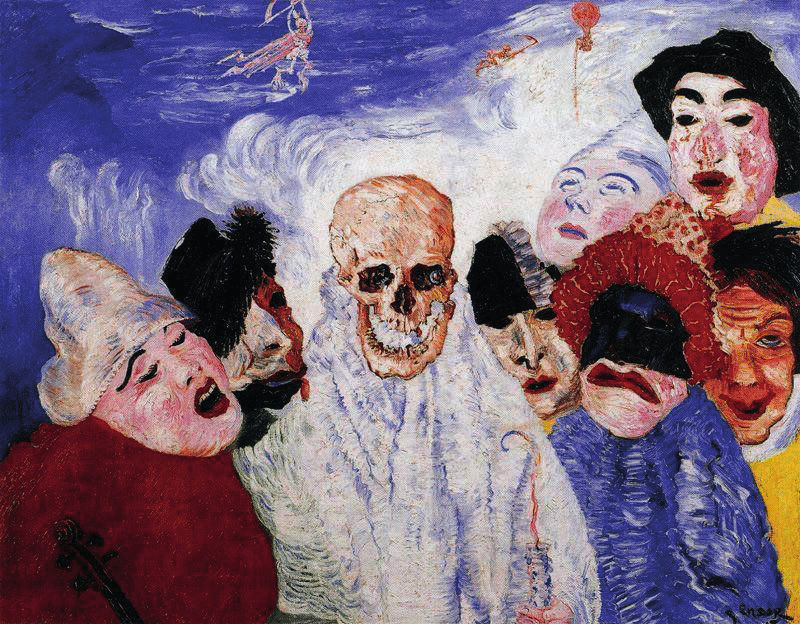

Masks….Yet Again.

James Ensor, Death and the Masks (1897). Source: https://www.artforum.com/print/previews/201007/james-ensor-26245I apologize for once again writing about damn face-masks. But as I mentioned a couple of posts ago, I spent the summer in France, and it was quite a shock to suddenly be somewhere in which wearing face-masks was no longer mandatory in public places - as they still very much are in Korea. I am also back in the classroom teaching students face-to-face, or rather, mask-to-mask, and I’m finding it a terribly demoralizing experience. The mask makes it difficult to recognize my students, but even more awful, completely erases one of the most important markers through which I receive signals of their active engagement with my teaching: their mouths.

Inevitably, this has got me thinking about the face-mask again as a sign of cultural difference, and why it is that Korean society finds it so much less onerous to wear them than do westerners. Why are the latter willing to take more risks with their own and others’ well-being than Koreans? Why is the calculus of relative pros and cons so different? In particular, I have got thinking about the trade-off between public health safety assessed in terms of viral infectiousness and social solidarity, as exemplified by Korea, and public health safety assessed more (and mostly unconsciously, I think) in terms of psychological well-being, humaneness, and the values associated with sociality and freedom, as exemplified by the west.

By now, I’ve read several psychological and medical reports about face-masks. I’ve found that while the physical health benefits are pretty much agreed on there is less consensus concerning their potential psychological toll. Are children being permanently or even temporarily mentally affected in negative ways by having to wear masks? To what extent is people’s capacity for empathy being temporarily or permanently obstructed? Are we being turned into abnormal or even sociopathologically solipsistic automatons?

My classroom of masked students is bad enough, but it is hard to conjure up a more visually graphic image of psychological social alienation than a subway carriage of Koreans bent over their smartphones and wearing masks (see my post from May 24th, 2022 for another take on the effect of smartphones in such situations). It also seems an especially powerful image of baleful subjugation and conformity. I can’t help but see the combination of face-mask and smartphone as constituting a socially and politically useful way of pacifying people, and also without any obvious coercion, as they are ‘self-medicating’ by apparent choice. The passengers are tranquilizing themselves by drastically narrowing their potential interactions with the immediate environment.

This is, to be sure, an environment that possesses a great number of visual, aural, olfactory and tactile stimuli that are likely to make any half-normal person feel uncomfortable, bored, or downright threatened, and that are not in any stretch of the imagination attractive, pleasant or benign. The mask aids and abets the healthy quest for secure environmental buffering. It is an excellent means of hiding oneself from the gaze of a disagreeable world. I don’t just mean the gaze of other people, but more metaphorically, the ‘gaze’ of one’s surroundings - the call to us made by these surroundings. of spaces with which we are actively connected and with which we instinctively expect to be able to respond resonantly.

The face-mask is a way of ensuring that one remains distant, detached, and disengaged. But in the subway the masking of the face is combined with the lowering of the head and the directing of the gaze towards a small illuminated rectangular screen. As I have discussed in a previous past, this dramatically limits access to the expansiveness of the visual field which the human eye has evolved to see. It produces a kind of tunnel vision, and, as the term in popular usage implies, involves a narrowing and impoverishing of vision. But the smartphone makes this seemingly detrimental action alluring because it substitutes the unpredictable, threatening, ugly, actual surroundings for surroundings over which one has complete control, that via the magic of the Internet offer potentially resonant relationships to the world rather than alienating ones. This is a very attractive trade-off, and no wonder everyone is eager to make it. We transports ourselves from the disagreeable place where our bodies are located in real time and space to another space replete with much more appealing stimuli.

A subway system anywhere in the world is never going to be a very appealing and enlivening environment, especially in the rush-hour. It’s inherently awful, really. No one in their right mind would choose to be there. But of course, we all ride the subway because we need to get to work or want to meet our friends. Like so much of modern city life, the environment through which we habitually move is an inherently alienating one. Not so much a concrete jungle as a concrete desert. The casting down of the gaze and the focusing of attention on a small illuminated screen, plus the concealing of the nose and mouth behind a mask are therefore highly efficient ways of blocking or buffering contact with one’s immediate surroundings and achieving a relatively robust form of autonomy and control. But obviously, these benefits come at a dreadfully high price.

*

I used the word ‘buffering’ above in knowing reference to the writings of the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, who juxtaposes the terms ‘buffered’ self with ‘porous’ self in order to make a basic distinction between the modern and pre-modern conceptions of identity within European society. The ‘porous’ self is an earlier model of human relationship to the world that characterized Europe prior to the seventeenth century. What Taylor describes as the uniquely modern ‘secular’ world is precisely a world in which relationship are no longer founded on ‘porosity’ of self but on the benefits accrued from the bounded of ‘buffered’ relationship of the self to the world.

Here is what Taylor says about the latter in A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007) : “As a bounded self I can see the boundary as a buffer, such that things beyond don’t need to ‘get to me’, to use the contemporary expression….This self can see itself as invulnerable, as a matter of the meaning of things for it.’ (p.38) A ‘buffered’ mode of existence “can form the ambition of disengaging from whatever is beyond the boundary, and of giving its own autonomous order to its life. The absence of fear can not just be enjoyed, but seen as an opportunity for self-control or self-direction.” (38-9) Thus, the ‘buffered’ self is characterized by a stance of disengagement from the world which is adopted because it accrues a “sense of freedom, control, invulnerability, and hence dignity”(285). Taylor notes that much of the value associated with this ‘buffered’ disengagement from the world has derived from the way in which it mirrors on the level of personal existence “the most prestigious and impressive epistemic activity of modern civilization, vz., natural science” (p.285), that is to say, the rational or objective point of view.

By contrast, there is the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. Here, “the boundary between agents and forces is fuzzy……[T]he boundary between mind and world is porous” (39). The relationship to the world is also what Taylor calls “enchanted”, by which he means that because there is no firm boundary between self and world, one feels intimately affected by the world in ways that continuously open one up to uncontrollable an mysterious forces. There is no clear distinction between the subjective and the objective, the interior world and the exterior.

In his study, Taylor is limiting his analysis to the western world, but it seems to me that his concept of ‘porous’ and ‘buffered’ selves can be extended to global proportions (with obvious caveats). It seems especially interesting in relation to cultures that have experiences rapid modernization under the aegis of western ways of thinking, and therefore have evolved rapidly from societies based on the ‘porous’ self to ones based on the ‘buffered’ self.

So, back to the Seoul subway carriage. Is it too much to suggest that the uniform behaviour of the Korean passengers of all ages (except the very old, who are not accustomed to smartphones!) can at least in part be understood by recognizing that they are living in a culture that has metamorphosized from one dominated by the pre-modern ‘porous’ self to one increasingly dominated by the benefits accrued by being a bounded, disengaged ‘buffered’ self - a self that makes one a fully-fledged ‘modern’ person? But the speed of change means that the characteristics of the ‘porous’ and the ‘buffered’ self co-exist in unique ways in Korea. For example, the high level of conformity manifest in Korean society is a clear reflection of a core characteristic or the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. As Taylor writes of European culture: “Living in the enchanted, porous world of our ancestors was inherently living socially. It was not just that the spiritual forces which impinged on me often emanated from people around me……Much more fundamental, these forces impinged on us as a society, and were defended against by us as a society……So we’re all in this together.” (42) Taylor’s words made me think of the collective reaction within Korea to Covid-19, and how they contrast to the western response, which was far more based on a ‘buffered’ sense of self in which individual autonomy has priority of the social sense of all being “in this together.” As Taylor adds, as a result of the pressure to subordinate self to group, in a society ruled by a sense of the ‘porous’ self there will be a “great pressure towards orthodoxy.” (42) But in contrast to this impulse, one can also very clearly observe in modern-day Korea other forces that derive from the adoption of the new bounded, ‘buffered’ sense of self, which prioritizes disengagement as a source of self-efficacy. As a result, , in the Seoul subway carriage we find the melding within the same person of characteristics of ‘porosity’ and of ‘buffering’ in relation to the self, of collective behaviour and disengagement.

Has the speed of social transformation been fundamentally traumatizing for Koreans? Are the visible exterior signs (the persistent mask, the obsessive zoning in on the cellphone screen) the manifested signs of an interior mental state that is, in a sense, a kind of mental and social derangement?