‘Keep yourself alive’

There’s a trend in Korea amongst young people to take sets of four passport-like photographic ‘selfies’ in shops that are sprouting all over Seoul. I use this interesting phenomenon as a jumping off point for some reflections on the violent nature of image-making.

A glimpse into one of the many Box Photoism shops in Seoul

There’s a trend in Korea amongst young people to take sets of four passport-like photographic ‘selfies’ in shops that are sprouting all over Seoul. One chain is called Photoism Box. The picture at the beginning of this post shows one such outlet near Anguk station. Apparently, this trend is yet to invade the west and is a specifically Korean phenomenon.

It began in 2017 with a company called Life4Cut. Here is what Lee Da-Eun of Korea JoongAng Daily says: ‘This analog manner of taking photos grew immensely popular with young Koreans, and numerous studios such as Photogray, Photoism, Harufilm, Selfix and more hopped on the photo strip trend, known in Korea as four-cut photos. Although there are distinct features for each type of photo booth, there are some common characteristics. All of these booths offer natural photoshop features, special seasonal photo frames, unique photo props to enhance the experience and QR codes that provide a digital copy of the photos taken. ‘

The writer suggests three reasons for the growing trend: first, it offers a relatively cheap way to capture lasting memories with friends and loved ones; second, it’s an optimal self-promotion tool to be used on social media. The third reason is especially thought-provoking: ‘The photo booths also reflect Generation Z’s pursuit of a more “analog atmosphere” in contrast to their very digital lives. Gen Z, or people born between the mid-to-late 1990s to the early 2010s, are most likely immersed in digital culture and less familiar with analog photography. In Korea, however, the younger generation is increasingly interested in a more analog culture and atmosphere, as they pursue film photography and instant self-photo booths.’

Note the text on the window on the Photoism ‘Box’, at the bottom left of my photograph: “Keep yourself alive” (also note that it’s written in English, not Korean). Interesting! The phrase made me wonder about what is really at stake not just in relation to selfies but in photography in general. What the slogan obviously means is that a photo print is a more tangible memory than a digital file. It’s something you can hold in your hands. And even though you will probably post them online! This is the analogue experience that young Koreans are apparently craving. But let’s dig a little deeper.

In English we say ‘to capture’ something when we take a photograph. We also say, ‘to take’ a photograph, which on the face of it seems less violent than ‘capture’. But etymologically, the two verbs are closely related. The Online Etymology Dictionary says for ‘to take’: ‘"act of taking or seizing," 1540s, from French capture "a taking," from Latin captura "a taking" (especially of animals), from captus, past participle of capere "to take, hold, seize".’ In relation to ‘to take’ , the dictionary says the verb comes from ‘late Old English tacan "to take, seize," from a Scandinavian source (such as Old Norse taka "take, grasp, lay hold”)’.

These are very aggressive and predatory verbs being employed in relation to the act of using a mechanical optical imaging device to produce a representation of something. I wondered if it’s the same in Korean. Do they also conceptualize this activity using belligerent metaphors?

It seems the normal way to say ‘take a photograph’ in Korean is 사진을 찍다 (sajin-eul jjigda). The word jikgda relates to the way of describing stamping something, like a document, or printing a book or picture. The Korean is distantly related to the Chinese for a ‘seal’ on a document. But jikgda can also mean ‘hew’, ‘strike’, ‘chop’. So, there is also an albiet more attentuated belligerent connotation lurking in the Korean language.. But the verb also preserves a more overt link to the idea that a photograph is a stamp or print, that it is something tangible. This link is not necessarily carried over in the English convention of using the verbs ‘take’ or ‘capture’, which rather imply that we have actually possessed the something we represent, not just made a lasting impression of it.

In English we in part employ the same vocabulary in relation to photographs as was used previously to talk about handmade image-making, such as painting. We say, the artist ‘captured a likeness of someone’ in their portrait. But we don’t say to ‘take’ a painting. Rather, we say ‘make’, ‘produce’, or ‘create’. The choice of ‘take’ implies that the intermediary visualizing technology provides a directly indexical copy of the source (the subject to be photographed), and suggests the absence of active intervention or proactive work by the one taking the photograph. But either way, what is at stake is the underlying idea that an image somehow seizes its referent. It is not a gentle action. The idea of ‘keeping alive’ brings to mind the possibility that preserving memories like this really is a kind of capture or enslavement, and that the problem then is how to keep what one has photographed ‘alive’, how not to ‘kill’ it.. So, it really is a question of ‘keeping alive’, although, strictly speaking, it’s already too late. The image is already a corpse. For what we do when we document the world in images is simultaneously lose it. This is because reality is process, and an image inevitably cuts into the process. It freezes, ‘enslaves’, or ‘kills’ it. In other words, if making an image is violent, then the likelihood is that, despite our best intentions, what we ‘capture’ is being enslaved and also in danger of dying.

*

A consideration of the conditions experienced by our hunter-gatherer ancestors is helpful here, because evolutionary biologists have shown the extent to which we are 'haunted' by 'ghosts' of past evolutionary adaptions, that is, are hardwired to negotiate the world as it was experienced over tens of thousands of years, not just the mere hundreds of centuries of historical time. Hunter-gatherer societies are characterized by the absence of direct human control over the reproduction of the species they exploit, and have little or no control over the behaviour and distribution of food resources within their environments. Foraging for food was a fundamental survival skill, and the basic need for food played a fundamental role in the progressive evolution of cognitive structures and functions that would make food available on a more reliable basis. Under such conditions, humans explored their environments with the purpose of discovering resources of sometimes limited availability. The term ‘epistemic foraging’ is used in cognitive neuroscience to describe goal-directed search processes that respond to the state of uncertainty, and describes human behaviour considered not only in relation to specific task-dependent goals, like foraging for food, but also wider responses to the environment. This context-dependent behavior applied not only to the physical space in which humans existed but also to the abstract context of thoughts and decision making that helped humans to deal with uncertainty.. Foraging for information was as vital as foraging for food, as exploration resolved uncertainty about a scene. This ‘epistemic foraging’ supplied the core abstract thinking that humans developed, and gave them an evolutionary edge.

We are primarily geared towards the reduction of uncertainty through increasing our control over the environment, and we use epistemological tools to ensure this. But as Hartmut Rosa writes in his excellent book 'The Uncontrollability of the World’, human relationships to the world can be divided between on the one hand a stance of violent and aggressive action motivated by the will to mastery and control, to ‘capture’ and ‘take’, and on the other, one of erotic desire or libidinal interplay which requires a more open and accepting attitude to the uncontrollability of the world. Hunter-gatherer societies are characterised by the latter relationship, but within the culture of modernity, as Rosa writes, 'We are structurally compelled (from without) and culturally driven (from within) to turn the world into a point of aggression. It appears to us as something to be known, exploited, attained, appropriated, mastered, and controlled. And often this is not just about bringing things – segments of world – within reach, but about making them faster, easier, cheaper, more efficient, less resistant, more reliably controlled.' Rosa sees four dimensions to the modern obsession with guaranteeing maximum control: making the world visible and therefore knowable: expanding our knowledge of what is there, and making it physically reachable or accessible, making it manageable, and making it useful. But this sense of mastery comes at a high price because it lead to alienation from the world - to a loss of what Rosa calls 'resonance', which 'ultimately cannot be reconciled with the idea of intellectual, technological, moral, and economic mastery of the world.' As a result, we exist mostly in a condition of profound alienation, inwardly disconnected from other people and the world. As Rosa writes: 'Modernity stands at risk of no longer hearing the world and, for this very reason, losing its sense of itself.'*

Image-making is closely linked to the need to encode the results of epistemic foraging. But when seen in this light, a dual origin of image-making suggests itself. It began as way of encoding a libidinous and reciprocal relationship to the world, but gradually shifted to become a way of encoding the desire to enhance mastery and control. This could be described as image-making as as a system of engendering versus image-making as a system of production. This distinction is intended to contrasts two basic ways of being in the world: one in which representation encodes a world in in which we see the world as our dwelling place, and the other in which we are set apart in a position of aspiring (but inevitably futile) omnipotence. But image-making as engendering slowing gave way to image-making as production as we moved towards ‘modernity.’

What we humans fear most is uncertainty – being uncomfortably surprised. What we want most is to be in control. But in what does ‘control’ lie? Metaphors of ‘taking/capturing’ that dominate European languages in relation to making images, and those prevalent in Korean, suggest a common root in the idea of separation and aggressive domination and are infused with the aspiration towards control. But the western metaphors imply a far more aggressive relationship to the world than the Korea. The desire for control, which os a primary means of reducing uncertainty through closure is matched elsewhere by more open relationships to uncertainty.

The west seems especially inclined to the former. This can be seen in a very tangible way if we consider the evolution of the European artist’s’ self-image. From the sixteenth century onwards, their posture in their studios was made to look like this:

The preference for this stance, recorded here in a late sixteenth century Flemish print now in the British Museum, had much to do with the new social role-model then being adopted by artists, which was moving away from anonymous artisan or craftsman to being more like people on the next rank up in society: the knights. But this stance can also be understood to reflect the emerging idea central to modernity, which is that humanity is primarily characterized by the ability to assert aggressive control over the world. It is interesting to consider that this physical stance coincides with the start of belligerent European colonising of the world. It is also interesting to note that it is not seen anywhere else in relation to the self-representation of the artist. It certainly contrasts markedly with the self-image of the East Asian artist, who worked seated, poised over a horizontally oriented surface. This seems much more closely aligned metaphorically with someone sowing seeds in the earth - a farmer - that is, someone much more inclined to consider the world a dwelling place, not as a place for violent conquest.

NOTES

The Korea JoongAng Daily article can be found at: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/01/03/national/kcampus/korea-photobooth-photodrink/20230103190906442.html

Hartmut Rosa’s book, ‘The Uncontrollability of the World’ was published by Polity in 2020.

The illustrated print is an etching after Johannes Stradanus’ painting of van Eyck in his Studio, c.1590. It’s screen grab from the British Museum’s website.

Acorns

I’ve been getting to know the oak tree. Turns out there are more kinds than I expected. Over 500, in fact. But in the UK and France there are basically just two indigenous species: the Pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) and the Sessile oak (Quercus petraea). Here in Korea, there are six indigenous species, and they are very different one from the other. Within just half a mile of our house we’ve identified five. Here are their acorn

This morning we woke up to the first frost of the season. But the temperature quickly rose, and as I write this at around 10.30am it’s already quite warm outside in the bright autumn sunshine.

I’ve been getting to know the oak tree. Turns out there are many more kinds than I expected. Over 500, in fact. But in the UK and France there are basically just two indigenous species: the Pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) and the Sessile oak (Quercus petraea), and they are almost identical – the difference lies most obviously in the fact that the former grows its acorns on stalks while the latter does not.

Here in Korea, there are six indigenous species, and they are very different one from the other. Within just half a mile of our house we’ve identified five. Here are their acorns:

This is how I’ve identified them: Top left: Korean oak (Quercus dentata). Top right: Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica). Bottom left: Sawtooth oak (Quercus acutissima). Bottom right: Oriental white oak (Quercus aliena). Bottom centre: Oriental white oak (Quercus aliena var. acutiserrata)…. Maybe.

The most common around here is the Oriental white oak, which also has acorns that are most like the ones I’m familiar with from England and France. But the most common nationwide are the Sawtooth and Mongolian oak.

Here’s a map showing distribution ratio within South Korea. Looks like we live in an area that’s more than 40% oak trees :

The Korean oak is my favourite, and it has really huge leaves. I took a photo with my hand superimposed to give some idea of just how big:

Over the past couple of weeks locals have been out collecting acorns because they are used to make a nutritious jelly – Dortori-muk. When I did a bit of research about acorns as a food, I came across this fascinating TED Talk by an American woman Marcia Meyer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vi-1s1Bjs4

The Geese have arrived (earlier)!

I have noted the arrival of the geese in a couple of previous posts. This year, they arrived about a week earlier than last year – in the last week of September. Why?

I have noted the arrival of the geese in a couple of previous posts (Oct.1 2019 and Oct.7 2020). This year, they arrived about a week earlier than last year – in the last week of September. Eventually, thousands of bean geese (Anser fabalis) winter around here, having come from their breeding grounds in Mongolia and thereabouts. Apparently, the FAD (First arrival dates), as it is technically called, has been getting earlier and earlier due to global warming. The authors of an article in the Journal of Ecology and Environment wrote back in 2018: ‘Average temperature of September in wintering grounds has increased, and the FADs of the geese have advanced over the 22 years. Even when the influence of autumn temperature was statistically controlled for, the FADs of the geese have significantly advanced. This suggests that warming has hastened the completion of breeding, which speeded up the arrival of the geese at the wintering grounds.’ (1)

I always find it reassuringly ironic that the geese have to fly over North Korea and the DMZ to get to us. In other words, for them, there is no divided Korea. There is no Korea, North or South, just breeding grounds and wintering grounds. Adopting a ‘bird’s eye view’ in this context helps to put human history in tragic and absurd perspective. But it also drives a deep wedge between the natural history that addresses the lives of the geese and the human history about the lives of North and South Koreans.

This year, the geese’s arrival coincided with my reading of Dipesh Chakrabarty’s excellent The Climate of History in a Planetary Age (2021). His book added an additional significance to the event. The annual rhythm of bird migration serves to reinforce the assumption that nature as a whole is permanently cyclical. But now that we’re in the Anthropocene we are becoming aware that while nature has clear repetitive cycles based on the changing seasons, these are far from eternal. They just seem that way because of our very limited sense of historical time. Geological time, which deals in millions of years, reveal that massive changes occur in nature, sometimes absolutely devastating changes.

But humanly-caused global warming is now happening at such an alarming rate that, as the geese’s migratory pattern demonstrate, nature’s rythmns are changing within our timescale, and are easy to recognize. As a result, Chakrabarty writes that it is now essential that we find ways to conjoin the facts of Natural History with those of Human History. Climate scientists are showing that we can no longer treat them as distinct domains: “In unwittingly destroying the artificial but time-honoured distinction between natural and human histories, climate scientists posit that the human being has become something much larger than the simple biological agent that he or she always has been. Humans now wield a geological force……. A fundamental assumption of Western (and now universal) political thought has come undone in this crisis.”

References:

https://jecoenv.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41610-018-0091-2

Dipesh Chakrabarty’s The Climate of History in a Planetary Age is published by Chicago University Press.

Masks….Yet Again.

I spent the summer in France, and it was quite a shock to suddenly be somewhere in which wearing facemasks was no longer mandatory in public places, as it still very much is in Korea. I am also back in the classroom teaching students face-to-face, or mask-to-mask. I am finding it a terribly demoralizing experience. The masks of my student make it difficult to recognize them, but even more awful, completely erases one of the most important markers through which I can receive signals of a student’s active engagement with my teaching – their mouths. This post incloves some more reflections on cultural difference as revealed through the protocols of wearing facemasks.

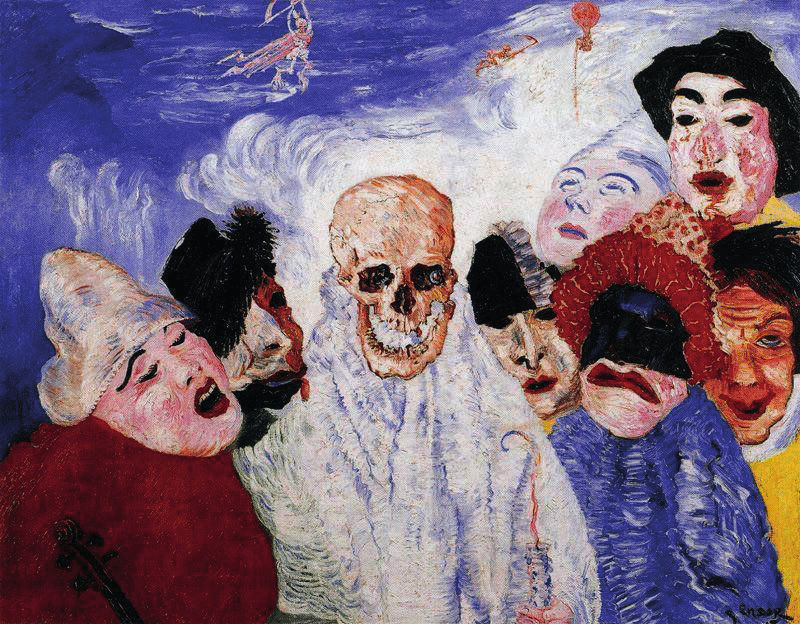

James Ensor, Death and the Masks (1897). Source: https://www.artforum.com/print/previews/201007/james-ensor-26245I apologize for once again writing about damn face-masks. But as I mentioned a couple of posts ago, I spent the summer in France, and it was quite a shock to suddenly be somewhere in which wearing face-masks was no longer mandatory in public places - as they still very much are in Korea. I am also back in the classroom teaching students face-to-face, or rather, mask-to-mask, and I’m finding it a terribly demoralizing experience. The mask makes it difficult to recognize my students, but even more awful, completely erases one of the most important markers through which I receive signals of their active engagement with my teaching: their mouths.

Inevitably, this has got me thinking about the face-mask again as a sign of cultural difference, and why it is that Korean society finds it so much less onerous to wear them than do westerners. Why are the latter willing to take more risks with their own and others’ well-being than Koreans? Why is the calculus of relative pros and cons so different? In particular, I have got thinking about the trade-off between public health safety assessed in terms of viral infectiousness and social solidarity, as exemplified by Korea, and public health safety assessed more (and mostly unconsciously, I think) in terms of psychological well-being, humaneness, and the values associated with sociality and freedom, as exemplified by the west.

By now, I’ve read several psychological and medical reports about face-masks. I’ve found that while the physical health benefits are pretty much agreed on there is less consensus concerning their potential psychological toll. Are children being permanently or even temporarily mentally affected in negative ways by having to wear masks? To what extent is people’s capacity for empathy being temporarily or permanently obstructed? Are we being turned into abnormal or even sociopathologically solipsistic automatons?

My classroom of masked students is bad enough, but it is hard to conjure up a more visually graphic image of psychological social alienation than a subway carriage of Koreans bent over their smartphones and wearing masks (see my post from May 24th, 2022 for another take on the effect of smartphones in such situations). It also seems an especially powerful image of baleful subjugation and conformity. I can’t help but see the combination of face-mask and smartphone as constituting a socially and politically useful way of pacifying people, and also without any obvious coercion, as they are ‘self-medicating’ by apparent choice. The passengers are tranquilizing themselves by drastically narrowing their potential interactions with the immediate environment.

This is, to be sure, an environment that possesses a great number of visual, aural, olfactory and tactile stimuli that are likely to make any half-normal person feel uncomfortable, bored, or downright threatened, and that are not in any stretch of the imagination attractive, pleasant or benign. The mask aids and abets the healthy quest for secure environmental buffering. It is an excellent means of hiding oneself from the gaze of a disagreeable world. I don’t just mean the gaze of other people, but more metaphorically, the ‘gaze’ of one’s surroundings - the call to us made by these surroundings. of spaces with which we are actively connected and with which we instinctively expect to be able to respond resonantly.

The face-mask is a way of ensuring that one remains distant, detached, and disengaged. But in the subway the masking of the face is combined with the lowering of the head and the directing of the gaze towards a small illuminated rectangular screen. As I have discussed in a previous past, this dramatically limits access to the expansiveness of the visual field which the human eye has evolved to see. It produces a kind of tunnel vision, and, as the term in popular usage implies, involves a narrowing and impoverishing of vision. But the smartphone makes this seemingly detrimental action alluring because it substitutes the unpredictable, threatening, ugly, actual surroundings for surroundings over which one has complete control, that via the magic of the Internet offer potentially resonant relationships to the world rather than alienating ones. This is a very attractive trade-off, and no wonder everyone is eager to make it. We transports ourselves from the disagreeable place where our bodies are located in real time and space to another space replete with much more appealing stimuli.

A subway system anywhere in the world is never going to be a very appealing and enlivening environment, especially in the rush-hour. It’s inherently awful, really. No one in their right mind would choose to be there. But of course, we all ride the subway because we need to get to work or want to meet our friends. Like so much of modern city life, the environment through which we habitually move is an inherently alienating one. Not so much a concrete jungle as a concrete desert. The casting down of the gaze and the focusing of attention on a small illuminated screen, plus the concealing of the nose and mouth behind a mask are therefore highly efficient ways of blocking or buffering contact with one’s immediate surroundings and achieving a relatively robust form of autonomy and control. But obviously, these benefits come at a dreadfully high price.

*

I used the word ‘buffering’ above in knowing reference to the writings of the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, who juxtaposes the terms ‘buffered’ self with ‘porous’ self in order to make a basic distinction between the modern and pre-modern conceptions of identity within European society. The ‘porous’ self is an earlier model of human relationship to the world that characterized Europe prior to the seventeenth century. What Taylor describes as the uniquely modern ‘secular’ world is precisely a world in which relationship are no longer founded on ‘porosity’ of self but on the benefits accrued from the bounded of ‘buffered’ relationship of the self to the world.

Here is what Taylor says about the latter in A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007) : “As a bounded self I can see the boundary as a buffer, such that things beyond don’t need to ‘get to me’, to use the contemporary expression….This self can see itself as invulnerable, as a matter of the meaning of things for it.’ (p.38) A ‘buffered’ mode of existence “can form the ambition of disengaging from whatever is beyond the boundary, and of giving its own autonomous order to its life. The absence of fear can not just be enjoyed, but seen as an opportunity for self-control or self-direction.” (38-9) Thus, the ‘buffered’ self is characterized by a stance of disengagement from the world which is adopted because it accrues a “sense of freedom, control, invulnerability, and hence dignity”(285). Taylor notes that much of the value associated with this ‘buffered’ disengagement from the world has derived from the way in which it mirrors on the level of personal existence “the most prestigious and impressive epistemic activity of modern civilization, vz., natural science” (p.285), that is to say, the rational or objective point of view.

By contrast, there is the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. Here, “the boundary between agents and forces is fuzzy……[T]he boundary between mind and world is porous” (39). The relationship to the world is also what Taylor calls “enchanted”, by which he means that because there is no firm boundary between self and world, one feels intimately affected by the world in ways that continuously open one up to uncontrollable an mysterious forces. There is no clear distinction between the subjective and the objective, the interior world and the exterior.

In his study, Taylor is limiting his analysis to the western world, but it seems to me that his concept of ‘porous’ and ‘buffered’ selves can be extended to global proportions (with obvious caveats). It seems especially interesting in relation to cultures that have experiences rapid modernization under the aegis of western ways of thinking, and therefore have evolved rapidly from societies based on the ‘porous’ self to ones based on the ‘buffered’ self.

So, back to the Seoul subway carriage. Is it too much to suggest that the uniform behaviour of the Korean passengers of all ages (except the very old, who are not accustomed to smartphones!) can at least in part be understood by recognizing that they are living in a culture that has metamorphosized from one dominated by the pre-modern ‘porous’ self to one increasingly dominated by the benefits accrued by being a bounded, disengaged ‘buffered’ self - a self that makes one a fully-fledged ‘modern’ person? But the speed of change means that the characteristics of the ‘porous’ and the ‘buffered’ self co-exist in unique ways in Korea. For example, the high level of conformity manifest in Korean society is a clear reflection of a core characteristic or the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. As Taylor writes of European culture: “Living in the enchanted, porous world of our ancestors was inherently living socially. It was not just that the spiritual forces which impinged on me often emanated from people around me……Much more fundamental, these forces impinged on us as a society, and were defended against by us as a society……So we’re all in this together.” (42) Taylor’s words made me think of the collective reaction within Korea to Covid-19, and how they contrast to the western response, which was far more based on a ‘buffered’ sense of self in which individual autonomy has priority of the social sense of all being “in this together.” As Taylor adds, as a result of the pressure to subordinate self to group, in a society ruled by a sense of the ‘porous’ self there will be a “great pressure towards orthodoxy.” (42) But in contrast to this impulse, one can also very clearly observe in modern-day Korea other forces that derive from the adoption of the new bounded, ‘buffered’ sense of self, which prioritizes disengagement as a source of self-efficacy. As a result, , in the Seoul subway carriage we find the melding within the same person of characteristics of ‘porosity’ and of ‘buffering’ in relation to the self, of collective behaviour and disengagement.

Has the speed of social transformation been fundamentally traumatizing for Koreans? Are the visible exterior signs (the persistent mask, the obsessive zoning in on the cellphone screen) the manifested signs of an interior mental state that is, in a sense, a kind of mental and social derangement?

Holding Heritage to Account

In today’s blog I include the second part of my talk for the International Conference on World Heritage, which was held in Korea in early September. The overall title was ‘World Heritage. Old Newness’, and my talk was entitled ‘Cultural Heritage as ‘Memory Event. The Case of Dansaekhwa’. In this second part, I widen the focus of my reflections to consider the crisis in the idea of ‘heritage’ in the West, and how it might relate to the idea of heritage in Korea.

In today’s blog I include the second part of my talk for the International Conference on World Heritage, which was held in Korea in early September. The overall title was ‘World Heritage. Old Newness’, and my talk was entitled ‘Cultural Heritage as ‘Memory Event. The Case of Dansaekhwa’. In this second part, I widen the focus of my reflections to consider the crisis in the idea of ‘heritage’ in the West, and how it might relate to the idea of heritage in Korea.

In my country, Great Britain, heritage is big business. We use the term ‘heritage industry’ a lot. In fact, it’s been argued that the entire island is one great ‘heritage’ theme park. Here’s an example of some of my heritage from near where I grew up in East Sussex in the south of England:

This is Bodiam Castle, built between about 1380-85. It still looks in remarkably good condition, doesn’t it? The interior, however, is a gutted ruin. Bodiam Castle is now owned by the National Trust, which looks after around 300 properties, and also manages great swathes of the British landscape, like this, the series of chalk cliffs on the South Downs overlooking the English Channel known as the Seven Sisters, also near where I grew up:

In relation to the arts, the National Trust website proudly announces: “no other organisation conserves such a range of heritage locations with buildings, contents, gardens and settings intact, nor provides such extensive public access.” Recently, however, the Trust became another victim of the on-going and increasingly crazy culture wars. In 2020 it published a policy review paper that addressed its properties’historical relationships to the slave trade and colonialism. As the UK’s Guardian newspaper’s website reported on November 12th 2020, the review paper “explored how the proceeds of foreign conquest and the slavery economy built and furnished houses and properties, endowed the families who kept them, and in many ways helped to create the idyll of the country house. None of this is news to most people with a passing acquaintance with history, and the report made no solid recommendations beyond the formation of an advisory group and reiterating a commitment to communicating the histories of its properties in an inclusive manner.” (1)

But it caused quite a furore. People on the political right, in particular, saw the Trust’s apparently guilt-ridden questioning and pathetic attempts at atonement as reprehensible evidence that its “ leadership has been captured by elitist bourgeois liberals”, as a letter from a group of enraged Members of Parliament put it - by people who were “coloured by cultural Marxist dogma, colloquially known as the ‘woke agenda’.”

What this little scandal reveals is the fact that the idea of ‘heritage’ is in crisis, at least in the West. The Guardian article goes on to mention the academic Patrick Wright, author of the best-selling On Living in an Old Country who, writing in 1985, described the National Trust as having been created as a kind of “ethereal holding company for the spirit of the nation”. But he was critical of this ideal, and his special target was the Prime Minster of the time, Margaret Thatcher, and her efforts to co-opt a certain image of Britain to help maintain her hold on power. Today, post-Brexit and in the light of the so-called ‘woke agenda’, the issues Wright raised back then have become even more pressing. Take Chartwell, Winston Churchill’s family home, which is also not far from my hometown:

Chartwell’s historical associations with the slave trade made it one of the Trust’s targets. As The Guardian noted, within the concept of heritage places “are easily mythologised as Britain’s soul, places in which tradition and inheritance stand firm against the anonymising tides of modernity. They are places of fantasy, which help us imagine a rooted relationship to the land that feels safe and secure. As Wright pointed out, this makes the project of preserving them necessarily defensive, and one that doesn’t sit well with the practice of actual historical research – which contextualises, explains and asks uncomfortable questions.”

The issue pivots on the problem of inheritance. Who in the present decides what is worth celebrating in the past, and how can they be held to account? What can or should be politely ignored or forgotten, and what must be condemned? At its worst, ‘heritage’ is an anodyne way of referring to the ownership of the past by the powerful in the present, who use it to help consolidate their position through permitting those with little or no power to enjoy some of the nation’s patrimony on the weekend without upsetting the status quo, while also allowing them to avoid dealing with the kinds of moral qualms and ambiguities that characterize the rest of their lives. Of course, there are far more positive ways to describe heritage. For example, that it a social category dedicated to countering the alienating effects of modern existence through providing the possibility of resonant relationships to the past.

I’m not sure to what extent the Republic of Korea should be engaging in the kind of mea culpa correctional process now going on in the West. Should you also be actively exposing the extent to which, for example, many of your admired Confucian scholars condoned slavery and the brutal subordination of women? Or is the Republic of Korea at a different stage of cultural development, or developing on a significantly different path, and so introducing ‘Western’ principles of social justice would actually be a new form of cultural colonialism? The context for the celebration of Korean heritage today is the legacy of Japanese colonization, rapid westernization, and an ideologically divided people. These facts demand a unique attitude to heritage to which everyone should be sensitive. The situation is very different to Britain, whose heritage nests within a far more unbroken and triumphalist story, one that is now in dire need of revision. Perhaps in Korea, the cultural situation demands a rather less uncompromising and aggressive relationship to its heritage.

Then again, the universality of the principles of justice now being employed to judge the past seems unquestionable. Slavery, the subjugation of women, these do seem morally repugnant wherever you stand – at least, if you’re standing in an open society that Is dedicated to maximizing the possibilities of human flourishing, at least in principle. But do we want to be reminded of these dreadful things - the past’s legacy of cruelty and woe - every time we visit our nation’s’ heritage. Must we always say, as Walter Benjamin did as the Nazi’s closed in, ‘There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.’ Won’t it ruin our day out?

But it is in this context that artists could be very useful. Their ‘unofficial’ view on things may help to enliven heritage. They don’t shy away from the truth, but they’re also not (or should not be) hanging judges standing on the moral high ground and passing judgement. Through perceiving the present’s similarities and differences from the past in more than a reactionary and traditionalist sense, but also in taking more than a stance of hostile deconstruction and critique, artists can show how to resist institutional sclerosis.

Notes:

(1) (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/nov/12/national-trust-history-slavery?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other&fbclid=IwAR2Ar4xEPtJ17i7QHdZZnMS8lCbb48T6TsOL8nMqU7jwb4QOnvCM-dd8bbs)All images courtesy of the National Trust.

Images courtesy of the National Trust.

Juche Realism: North Korean Art.

First part of my analysis of North Korean Art

In today’s post, which is Part 1 of two posts, I’m going to discuss the kind of art that is mandatory in the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea.

It’s called Juche Realism. Here are some examples:

Jo Jong-Man, ’After Securing Arms’, watercolor on paper, 1970s. Depicting a heroic episode from the Korean War. (Image via cctv-america.com)

Park Ryong Sam, ‘Farewell’, 1977. watercolour on paper. Another Korean War narrative. (Image via https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/north-korean-art)

Unknown ‘The Year of Shedding Bitter Tears’, Fragment 2, c.1994, watercolor on paper. This collectively painted work was made to commemorate the death of Kim Il-sung in 1994. (Image-grab from Yoon, Min-Kyung, “Reading North Korea through Art’, Border Crossings. North and South Korean Art from the Sigg Collection, ex. cat., Hatje Kantz/Kunstmuseum Bern, 2021)

A totalitarian ideology, Hannah Arendt wrote, “differs from a simple opinion in that it claims to possess either the key to history, or the solution for all the ‘riddles of the universe,’ or the intimate knowledge of the hidden universal laws, which are supposed to rule nature and man." In the DPRK, the inevitable non-realisation of the prophecy meant that as in the Soviet Union, which installed Kim Il-sung in power, Kim was soon obliged to devise strategies for cushioning the masses from the realities of failure and the oppression of authoritarian rule. But as was the case in Stalinist Russia, Kim realized that it wasn’t necessary to strive to make real external conditions match ideological goals; it was only necessary to change how the masses experienced external conditions by censoring all dissenting views and veiling day-to-day reality by a fantasy world created by artistic means, a fantasy world whose content derived wholly from the state-generated mythology.

As I discussed in a previous post (June 21st, 2020, ‘North Korea: ‘Theater State’), the DPRK has developed a complex system of rituals in which the public space becomes a theatre in which allotted roles are played by all North Koreans. The entire population is regularly called upon to perform in the fantasy ‘total work of art’, in which actions are determined by externalized modes of interaction. Life is thereby ‘aestheticized’ by turning it into something to be enacted rather than acted upon, and the real locus of social life is the public not the private space. The North Korean people become submissive performers of a fabricated life, rather than free and self-determining agents in a real one. This is perhaps most explicitly demonstrated in the annual Arirang Games, which involve elaborate displays of huge numbers of people working in precise unison in synchronized movements. It is also evident in the extraordinary spectacles of collective mourning that followed the deaths of Kim Il-sung in 1994 and his son Kim Jong-Il in 2011. Such ritualized mourning was emotional expression on the collective level and unrelated to individual psychology.

Vasily Sergeyevich Orlov, ‘Native Land’, 1930s, oil on canvas. An example of Soviet socialist Realism, the model for North Korean Juche Realism. (Image: https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/socialist-realism-art)

Art plays an important role in organizing and directing the state ‘performance.’ Like Soviet Socialist Realism upon which Juche Realism is based, such as the example shown above, painting in the DPRK is characterized by narrative allegories in the style of illustrational figuration - ‘illustrational’ in the sense that a clear message is unambiguously communicated. It is, in effect, a perverted form of nineteenth century History Painting, involving the staging of significant narratives for dramatic effect. But while North Korea’s artistic culture was initially merely imitative of Soviet Socialist Realism, it soon displayed significant signs of deviation to bring it into line with the more general deviation from Marxism-Leninism in state ideology. This was defined as ‘Kimilsungism’, and later, as ‘Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism’, after his son, Kim Jong Il became leader.

Kimilsungism was formulated for the Korean people uniquely, and involves a transferral of political focus from the international to the national level, and a rhetorical shift from expressions of class unity and struggle to the unity of the North Korean people. Central to the new doctrine is the uniquely North Korean concept of juche, which derives etymologically from ju, meaning ‘the main principle’, and che, ‘body’ or ‘self’. The compound word is therefore usually interpreted as referring to ‘sovereign autonomy,’ ‘self-determination,’ or, most commonly, ‘self-reliance.’ As a political philosophy, ‘Juche thought’ was largely designed for foreign consumption, and intended to bring the regime an aura of political legitimacy and profundity. But the principals of ‘juche’ nevertheless informed the visual aesthetics of North Korean art, contributing to its salient characteristics, and determining how it differed in terms of technical media, themes, and mood from the Soviet model.

In 1966 Kim Il-sung delivered a speech entitled ‘Let Us Develop Revolutionary Fine Arts’ in which he sought to distinguish Korean-style Socialist Realism and introduced the concept of 'Juche Realism'. His son and heir Kim Jong Il subsequently codified the principles in a book entitled On Fine Art (1991). While the outlook of Soviet Socialist Realism was intentionally international, Juche Realism was fundamentally nationalistic, forging an inseparable link between individual North Koreans, the people as a unified community, and the state based on the ideal of national autonomy. At first, in emulation of the Soviet Union, the western materials of oil on canvas were dominant media, and while they continued to remain important North Korean artists from the late 1950s were trained onward in a style dubbed Joseonhwa (or Chosonhwa) - Joseon-painting or DPRK painting (‘Joseon’ is how North Korea refers to itself). What makes Joseonhwa distinctive is not so much a deviation in figurative style from the basic conventions of Socialist Realism, however, but a change in the media employed: ink or colored water-based paints on paper. These are the traditional painting media of East Asia (China, Japan, and Korea), and the decision to adopt and adapt them was as a practical display of ‘Juche’ enacted on the level of technique, of relying on indigenous resources and conventions rather than foreign ones. But this decision also aimed to be a critique of the local tradition. For, in contrast to the literati or scholar-nobility conventions of pre-modern Korea, which derived from China and favoured monochromatic works in ink on paper or silk, Joseonhwa paintings are made in bright colours.

Three main narrative themes in Juche Realism can be identified, which to some extent parallel those of Soviet Socialist Realism: the triumph of heroism over adversity; love of the leader and the nation; and abundance in food production. As such, prominent subjects in Juche Realism are scenes of individual and group acts of heroism and courage, particularly related to the life of Kim Il-sung as a guerrilla fighter in the insurgency against the Japanese in China during the 1930s and 1940s, and during the Korean War (which according to the DPRK narrative, had been started by the ROK and ended in DPRK victory). These scenes also feature ordinary male and female soldiers and depict the overcoming of great obstacles through heroic and superhuman effort. The second typical theme concerns the expression of the tender, paternal, love of the Kim leadership for the North Korean people, and the reciprocal affection of the people for their leader. Third, there is the theme of abundance in food production, exemplified, for example, by paintings of Kim Il-sung visiting collective farms. In this case, the goal is to demonstrate that under benign leadership the DPRK possesses a perfectly efficient infrastructure that binds all sectors, providing not just communal sustenance by abundant flourishing.

At the heart of Juche Realism lies a kind of “revolutionary romanticism”, which especially emphasises pathos. The aim is to instruct the North Korean people in how to see, feel, and internalize the historical truth as presented by the DPRK’s ideology, thereby gaining mass compliance through emotionally moving the people via the representation of inspiring, comforting, and confidence-boosting tableaux with which they can readily empathize and use as models of correct behaviour to emulate and mimic. Images express affirmative feelings which demonstrate that the leader has the capacity to overcome all adversity and to continuously give birth to the new society. Juche Realism creates an imaginary “alternative reality”, one whose goal, as the art historian Min-Kyung Yoon puts it, is the “visualization of an emotional truth that conveys values rather than factual accuracy.” These emotional truths become the basis for historical truth. Thus, the idea of ‘truth’ is epistemologically flattened and conflated with the official narrative controlled and disseminated by the regime, which admits no heterodoxy or challenges by parties outside the regime.

So, the world Juche Realism evokes is an illusion beyond realization in the material world, and while it employs the conventions of mimetic realism, it is not involved in recording reality but in producing it. In this sense, Juche Realism is performative rather than descriptive. Paintings are visual texts made up of signs whose power to influence occurs primarily on the level of affect, feeling, and emotion rather than discursively as conscious and rational reflection. Because of the monopoly over representation possessed by Juche Realism it functions as a powerful source of mimetic social behaviour. Indeed, no other sources of mimetic behaviour are available. The North Korean people thus are compelled to uniquely imitate the idealized conduct, actions, and practices that are depicted, and in a feedback loop this behaviour is consolidated and duplicated in everyday life. It is this mimetic circle that creates the bridge between the fictive world of representation and the actual world of social interaction. Furthermore, the idealized nature of the behaviour guarantees that mimetic behaviour takes place despite actual, real-world, evidence that contradicts the idealization. The result is that a situation is produced in which elevated emotional such as self-esteem, reduced anxiety and depression, and a general sense of well-being are encouraged and channelled toward the maintenance of the status quo.

Juche Realism functions as a pedagogy of submission. It helps construct a social myth that shields the North Korean people from uncertainty, expressing the guarantee that under the Kim leadership they are safe from all danger. Through their status as performers within the state ritual, they receive a positive sense of collective power, efficacy, and confidence. In existential terms, Juche Realism facilitates the goal of the DPRK’s authoritarianism, which is to engineer the mass relocation of agency from the individual to the collective, and thereby to the state. Juche Realism aids and abets the process wherein the individual is radically deconstructed to become an integral part of a collective and eternal socio-political ‘organism’.

Juche Realism should therefore be distinguished from propaganda, if by this term one only refers to the purveyance of biased or misleading information. For in Juche Realism the ancient wish-fulfilling power of the image, which binds art to sacred ritual and supernatural belief, has been carried over into a secular system. Juche Realism is a form of transformational imagery which is part of the wider ritual process that channels the supernormal or extramundane powers purportedly embodied in the reigning ideology. Juche Realism is therefore fundamentally different from secular western humanistic art whose conventions of figuration it appropriates, linking it to a pre-modern worldview in which the image is a powerful talismanic presence to be utilized within communal rituals of piety and devotion. The cultic dimension of Juche Realism is most obvious in the reverence shown toward the portraits of the Kim leadership, which are treated like sacred icons - especially portraits of Kim Il-sung, who is worshipped as provider, healer, and saviour.

In my next post, Part 2, I will think about Juche Realism’s success in creating a consoling aura of delusional optimism that serves to pacify the North Korean people..

A Rose a Day No. 27

This is photo take yesterday by Eungbok, my partner, of me and the most common species rose in these parts, Rosa multiflora. It was taken while on a walk on an oak covered hillside near where we live. An important species rose in China, Korea, and Japan, it is similar to the Dog Rose, but with white five petalled flowers rather than pink, and large yellow stamens. The petals are serrated and often heart shaped, and the fragrance very delicate, and when the plant is mature, they come in very profuse clusters or panicles on long, arching canes.

This is the specimen in our garden:

Sometimes, as the petals age, they are tinged with pale pink:

As you can see from the photo of me and Multiflora, it bears a lot or round red hips - the fruit of the rose – in autumn.

A few years ago, I uprooted a specimen of Rosa multiflora from nearby, where it was growing bordering a road, and planted it in our garden. In Korea this rose is commonly called ‘Jjillekkot’ – ‘Mountain Rose’. There is a popular song by Jang Sa-Ik about it. Here is a translation of the first verse:

White flower, Mountain Rose,

Simple flower, Mountain Rose.

Sad like a star, Mountain Rose,

Doleful like the moon, Mountain Rose.

Since hearing this song, I can but see the Multiflora in our garden as sad, an impression that the sparseness, thinness, and the arching trajectory of the canes tends to encourage. We made the mistake of pruning it back a couple of years ago, and it protested by barely blossoming last year. This year, however, it put on a very multifloriferous show. It has also multiplied, and there are now five more Rosa multiflora plants growing in our garden!

Rosa Multiflora is also popular rootstock, especially in colder climates. Early on in my life as a rose gardener I was surprised to find in my garden in France buds growing on some cane whose wood and leaves looked different, and whose blossoms then turned out to be quite different from the rest of the rose. I learned that this was the suckers of the rootstock sprouting from below a portion of the stem and root system onto which a bud eye had been grafted. If you don’t cut these back, they may very well take over, reverting the rose to the rootstock, such as Rosa laxa, ‘Dr. Huey’, or Rosa multiflora. Furthermore, one can uproot a rose and replant it, and then find its rose’s rootstock suckers pushing their way through where the now re-relocated rose once grew. As a result, I have a vigorous Rosa multiflora growing in my French garden, just like the one I transplanted from the nearby hillside in South Korea.

The Korean Dead

In today’s post I want to talk about death. Well, the burial of the dead. Within a square mile of my house there must be over a hundred grave mounds scattered around the hills, some quite elaborate but most very simple. I recently went on a walk and photographed some of the ones I passed.

The way Koreans traditionally bury their dead is evidently very different from the Christian West. Basically, these mounds are what historians call tumuli – from the Latin for ‘mound’ or ‘small hill’ – an ancient and truly global burial convention. It seems the Koreans continued to inter their dead in a manner that long ago died out (excuse the pun) in other parts of the world, especially in areas dominated by Christianity. Koreans traditionally buried their dead under the mound upright in a coffin made from six planks of wood . These planks represent the four cardinal points on the compass, in addition to a plank for heaven and one for earth. Corpses either face south or toward some important spiritual part of the landscape, like a mountain.

There are more than the usual number of such burial mounds around the DMZ because many exiles from North Korea opt to be buried as near as possible to their homeland. But actually, the whole of the Korean peninsula is a massive graveyard. Everywhere you go in the hills and mountains – as you cruise along a highway, for example – you will see these tumuli graves dotting the landscape.

They don’t seem macabre or haunted. On the contrary, they are life-affirming. According to the Taoist-Confucian worldview, when someone dies not everything related to them disappears. Death involves a separation of hon (soul) and baek (spirit). Within this cosmology, which sees reality as the perpetual interacting of yin and yang - heaven and earth - yin is the negative or passive force of the earth, while yang is the positive active force of the cosmos. Together, these interrelated forces are nature. In other words, the burial traditions arises from an awareness of existence as perpetual change driven by yin and yang, and it is understood that for the living to achieve a balanced life they must aim to exist in harmony with these two forces.

Hon is regarded as yang, and upon death it leaves the material dimension and returns to the immaterial heavenly realm from which it arises. Baek is regarded as yin, and is the dimension of the human bestowed by the earth. When someone dies, with the decay of the physical body baek returns to the earth. This means that a grave is the place where someone’s baek resides, and this is why it is called a ‘yin-house’ (eum-gye). People therefore reside in two ‘houses’ – the ‘yang-house’ (yang-gye) of the living, and the ‘yin-house,’ where rests the baek of the deceased ancestors. The bones of these deceased lying beneath the grave mound are the connecting link between the deceased and their offspring, and the burial mound or ‘yin-house’ must exert a positive influence on the living offspring, because if neglected it will exert a negative influence, transmitting bad energy. This is one important reason why the eldest son of a family is duty-bound to clean and prepare the burial mound of their most recently deceased ancestor, and family members must pay their respects before the grave. This happens at Ch'usok, the day dedicated to the ancestors, on which families gather from all over the country at their ancestral graves.

To me, these ‘yin-houses’ are obviously analogous to a woman with her legs open giving birth or a gestating woman with her arms around her pregnancy. But this makes only limited sense according to the convention described above. Officially, what a Korean grave says is that we reside in two worlds - one of the soul and one of the spirit, and the grave is associated with the latter. But it seems possible that these mound-graves date much further back than the yin-yang cosmology of Taoism and Confucianism, and are linked to an essentially shamanistic or animist worldview.

Animism has been largely misunderstood, but recently a major reassessment has occurred which stresses the fact that animist societies - such as indigenous hunter-gatherers today - have a fundamentally earth-relatedness cosmology. In an animist worldview there is understood to be an intimate kinship between the human and the natural world. The realm of plants, animals, and human interpenetrate. But more than this. As Graham Harvey writes: ‘animists are people who recognise that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship to others. Animism is lived out in various ways that are all about learning to act respectfully (carefully and constructively) towards and among other persons’. (Graham Harvey, ‘Animism: Respecting the Living World’, 2006, p. xi).

When seen in this animist context, the Korean grave-mound seems to be an exemplary symbol of a belief system in which interpenetration of the human and nature is central. Humans envisage their dead as being recycled - re-birthed – within nature, a process symbolized as a person – a pregnant or delivering female human. But the custom seems to have become overlayed with the moralism of Confucianism, which separates the heavenly world from the earthly, and stresses filial piety, the duties of the living to the dead, rather than consubstantiality between everything of heaven and earth. Flesh and earth, hair and plants, consist of the same fundamental substance, and one is continually transmuted into the other. In this sense, the Korean mound-grave speaks of kinship between humans and the rest of the natural world. Along with this went notions of care, responsiblity, soldidarity, and deep appreciation.

But it should be noted that modern-day Koreans have abandoned this tradition. They increasingly cremate their dead nowadays, and inter them in cemeteries that are modeled on the Christian convention of the centralized, enclosed cemetery. My partner’s father was cremated and is interred in a massive cemetery for former armed service personnel (he was born in North Korea and fled south and fought for the Republic of Korea in the Korean War). This cemetery looks very like rows of apartment buildings for the dead. Today’s preferred model for the ‘yang-house’ in Korea is also the preferred model for its ‘yin-house’.

Korean Shamanism

A mudang at work.

In a previous post I mentioned shamanism in South Korea. It will probably come as a surprise to learn that shamanism is alive and well in this country, where it is practised alongside other religions.

So, just what is shamanism? The term is used by anthropologists, rather than any actual believers, and derives from a word in the Tungus language of Siberia, which is where the first anthropological studies were conducted. Shamanism, one can say, is the first of humanity’s spiritual belief systems, and is a form of animism. A person acknowledged by their community to be a shaman is believed to have mastered the world of the ‘spirits.’ The shaman ascends to the sky to commune with the spirits of the human dead and those that inhabit all of nature, or experience possession, the descent of spirits into their own bodies. In the first case, the anthropologists say the shaman becomes the equal of the celestial forces, while in the second they are the means of its incarnation. Shamans are considered experts at channeling and riding the often dangerous energies that pervade the world. In Korea, shamanism is an ancient, deep-rooted and still enduring tradition, though one that is largely unpublicised because it is considered a ‘primitive’ cultural residue that runs contrary to Korea’s modernising project.

Importantly, almost all Korean shaman are women, called mudang, and one ceremony they are especially called upon to perform is called a gut. This is undertaken for different purposes, such as after a death, or for exorcisms. The mudang sets up an altar, and going through multiple costume changes, and using props including, masks, paintings, fruit, and paper flowers, becomes ‘possessed’ by the psyolsang – the spirits. These spirit avatars can be traditional animist gods, which are often animals, or Buddhist bodhisattvas. But nowadays, the spirits can also take the form of Jesus and the angels, or even people like General Douglas MacArthur. He is an important man for Koreans, said Hazel. The costumes represent the various spirits the mudang is channeling, and during the ceremony she will interpret the spirits’ message to her.

Shamanism in Korea is also very secretive. Though many Koreans consult mudang, they are usually embarrassed to admit it, because shamanism smacks of superstition and is deemed culturally backward. But Korean people continued to arrange visits in secret. This was not so much in fear of breaking the law, however, but because of the shame they’d feel if it became known in their own community. They continue to go for many reason: because they are sick or mourning the death of a loved one, because they want something or someone, or want to curse them, or more generally, because they are anxious about what the future holds for them or their loved ones.

Many older Korean people believe they are afflicted by an debilitating emotion called han, a feeling of animosity, bitterness, malignancy, and a profound sense of being ill at ease with what seem to be the obvious injustice of the world. Han has greatly occupied Korean culture, and many ways have been developed for purging souls of the malaise. It seemed that one of the principal roles of the mudang is to satisfy this han, the grudges, of the dead, and to pray for their peace. Through connecting with the spirit world, they cleanse the world of the living of the bitterness of the dead.