Axe Murder at the DMZ!

On August 18, 1976, about a mile from where I live, near the Bridge of No Return – a ruined bridge that became famous during the Korean War because it was a key route south - the infamous ‘axe murder incident’ occurred. The reason it’s come to mind recently is because it involved a poplar tree.

My growing interest in trees, especially in oak trees, reminded me of something I read a few years back concerning a very dangerous moment at the DMZ.

On August 18, 1976, about a mile from where I live, near the Bridge of No Return – a ruined bridge that became famous during the Korean War because it was a key route south - the infamous ‘axe murder incident’ occurred. The reason it’s come to mind recently is because it involved a poplar tree.

This tree limited visibility for the United Nations Command checkpoints, and so on that fateful day in mid-August five South Korean civilian workers accompanied by UNC guards were dispatched to prune it. As they were at work, two North Korean officers and a dozen soldiers suddenly appeared demanding the workers stop. When they ignored the request and continued working, more North Korean soldiers arrived in a truck and set upon the workers and their military escort with clubs and axes. The JSA Company Commander, an American, Captain Arthur Bonifas, and his First Platoon Leader, First Lieutenant Mark Barrett, were killed. Here’a a photograph:

Immediately after the incident, the United States and South Korea announced ‘DEFCON 3 ’ and the United States dispatched F-4 and F-111 fighter-bomber to South Korea and sent the aircraft carrier ‘Midway’ to the west sea. The act of tree prunning pushed the Korean Peninsula to the brink of war. But the crisis was defused when Kim Il-sung expressed his regret, sending a letter of apology to the UNC. Later, the UNC carried out Operation ‘Paul Bunyan’ – named after the giant lumberjack and folk hero in American and Canadian folklore - and cut the offending tree down to an ugly stump. That’s what’s happening in the photograph at the top of this post. Here’s what it looked a couple of decades after the Operation:

Later, this stump was cut down and replaced by a plaque where the tree once stood, which is what you can see today:

What was going on in the minds of the North Koreans that day? What made them over-react so violently? Were they especially fond of this particular tree? Perhaps they saw the dismemberment of a tree as subliminally mirroring the dismemberment of Korea, of the Korean people. It’s sad that the UNC decided to take it out on the poor tree. It was of course entirely blameless. It just had the terrible misfortune to be growing in a very dangerous place – well, dangerous for humans. From the look of the photographs, the tree was in its fifties, or thereabouts. It definitely predated the division of the Korean peninsula and the Korean War.

I was at school doing ‘A’ levels in 1976, and we studied the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins as part of the course. By coincidence, he wrote a moving poem about some beloved poplar trees being cut down next to the River Thames. Here’s the Hopkin’s poem. I suppose it could also serve as a memorial for the DMZ poplar, too:

felled 1879

My aspens dear, whose airy cages quelled,

Quelled or quenched in leaves the leaping sun,

All felled, felled, are all felled;

Of a fresh and following folded rank

Not spared, not one

That dandled a sandalled

Shadow that swam or sank

On meadow & river & wind-wandering weed-winding bank.

O if we but knew what we do

When we delve or hew —

Hack and rack the growing green!

Since country is so tender

To touch, her being só slender,

That, like this sleek and seeing ball

But a prick will make no eye at all,

Where we, even where we mean

To mend her we end her,

When we hew or delve:

After-comers cannot guess the beauty been.

Ten or twelve, only ten or twelve

Strokes of havoc unselve

The sweet especial scene,

Rural scene, a rural scene,

Sweet especial rural scene.

But when I was 17-18 years old it never even occurred to me to find out what a poplar tree actually looks like! They are indeed lovely-looking trees. They grow very tall and straight, and the leaves are oval to heart shaped. There’s a fine mature specimen standing next to the lake beside the university where I teach, and as I’m just getting started as a tree-lover, it took me a while to identify it.

On re-reading Hopkins’ poem, I’m struck by how it seems to have taken on a renewed poignancy in the light of the potential planetary catastrophe that is looming. Especially the lines: ‘even where we mean / To mend her we end her/ When we hew or delve’.

Image sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_axe_murder_incident

https://twitter.com/korean_dmz_vets/status/1364922717707845635

Some thoughts after the Itaewon Halloween’s Day tragedy

Some thoughts in the light of the Itaewon tragedy that occured over the Halloween weekend.

The alleywaynext to the Hamilton Hotel, Itaewon, Seoul, photographed after the tragedy.

Two events happened to me in 1966 that now, in retrospect, I can see have helped shape my life.

I was eight years old.

The first event took place on 21 October. The Aberfan disaster. A colliery spoil tip above the south Wales’ village collapsed after heavy rain and engulfed part of it, including a school. 109 children of more or less my age and 5 adults were killed in the school. In all, 116 children and 28 adults died in Aberfan.

I vividly remember learning about the tragedy on the evening BBC television news. For some reason, I was at home all alone, which exacerbated the impact of the disaster. The room was dark, the only light was that coming from the black-and-white tv screen. Suddenly, as I took in the awful news, my bubble of childhood innocence burst. I learned that life is tragic.

In fact, you could say that Aberfan was important because, for me, it was a small version of the primal scene that is especially central to Buddhism: Prince Siddhartha’s awakening to the reality of suffering. In the story, his father had sought to protect him from the awful truth, and the prince was already in his late twenties when he is finally exposed to the reality of suffering for the first time. He witnesses three instances: someone very old, someone stricken with illness, and a corpse. Siddhartha was so deeply disturbed by what he saw that he realized he could not go back to his old coddled life. But he’d also been exposed to a fourth sight: a wandering monk seeking spiritual freedom. It was this exemplary figure that helped him see what path he must follow.

I guess you could say that without being conscious of it, of course, the discovery that late October day in 1966 that life included seemingly random and meaningless tragedies, and to people just like me, signalled the moment that I too out on my own ad hoc and decidedly less world-historically significant life journey in search of answers to why there is suffering. I seemed to be immediately aware that the answer was not to simply ignore such awful events and carry on, which is another version of Siddhartha’s father’s goal, and one that society colludes in encouraging. The Aberfan disaster was clearly part of the totality of human existence, and needed to be included somehow in life’s meaning. At first, it seemed the Christianity in which I was brought up had the answers, but I eventually got disillusioned and began looking for alternatives, and I’m still looking.

But there was another momentous event for me in 1966, and this was also brought to me via television. This life-changing event happened about three month earlier, on 30 July. This was the day when England’s soccer team won the World Cup, beating West Germany 4-2 after extra time. It was a truly ecstatic moment!

Again, I remember it well. Immediately afterwards, I ran out into the garden, where all was sunlight, warm and bright, and started to kick around a football. In fact, I was so inspired that, there and then, I decided to take the game seriously, and soon was very good at it, or at least, good enough to play right-wing for my schools’ teams up to the age of 18.

Now, England winning the world cup was obviously a very very different kind of decisive moment to the one triggered by the Aberfan tragedy. This event, which seems in my memory to be wonderfully illuminated, awoke me to joy.

When I look back over my life I see it is arraigned along a dark line of tragic events unfolding relentlessly one after another - from Aberfan to, now the latest, Itaewon. But I also see a luminous line of glory and joy. It seems to me obvious that for a philosophy of life to be complete it needs to somehow incorporate both these responses to the world. You can’t have one without the other. In fact, they define each other, are co-dependent, as exemplified by the Taoist symbol:

Eventually, Siddhartha answered his question about why there is suffering and how to overcome it by discovering what in Buddhism are known as the Four Noble Truths. Here they are, as listed on the ‘Theravada’ website:

All beings experience pain and misery (dukkha) during their lifetime:

“Birth is pain, old age is pain, sickness is pain, death is pain; sorrow, grief, sorrow, grief, and anxiety is pain. Contact with the unpleasant is pain. Separating from the pleasant is pain. Not getting what one wants is pain. In short, the five assemblies of mind and matter that are subject to attachment are pain“.The origin (samudaya) of pain and misery is due to a specific cause:

“It is the desire that leads to rebirth, accompanied by pleasure and passion, seeking pleasure here and there; that is, the desire for pleasures, the desire for existence, the desire for non-existence“.The cessation (nirodha) of pain and misery can be achieved as follows:

“With the complete non-passion and cessation of this very desire, with its abandonment and renunciation, with its liberation and detachment from it“.The method we must follow to stop pain and misery is that of the Noble Eightfold Path (Right View. Right Thought. Right Speech. Right Action. Right Livelihood. Right Effort. Right Mindfulness. Right Concentration).

The problem I have with at least some versions of Buddhism is that they can suggest that to transcend suffering you also have to transcend joy. Isn’t this what “complete non-passion” implies?

Well, yes and no. There are certainly tendencies within Buddhism that push a rigid asceticism in the name of overcoming desire, and so seem to throw the baby of joy out with the bathwater of suffering. But other tendencies within Buddhism seem to be able to strive to accommodate both. For example, take these words of the Korean Seon (Zen) Buddhist SongChol, who died in 1993, from the wonderful collection of his Dharma messages, ‘Opening the Eyes’:

Everyplace we sit or stand is a golden cushion or a jade stool and we all dance to lively tunes amidst the beauty of nature. Lift up your eyes and look at the infinite great light that always pervades the universes. In fact, the universes themselves are this great light. So let’s join hands and move forward in this eternal light, for there is nothing but peace and freedom and joy and glory right before our very eyes.

*

It is striking that my two ‘epiphanies’ in 1966 came courtesy of television. Interestingly, the transfer of the information via technological mediation did not significantly diminish the emotional and personal impact on me of the events taking place far away. Of course, I was less affected than I would have been if I’d actually been present at the events that moved me. But I was still powerfully impacted.

Perhaps nowadays it’s different. Are people so thoroughly inundated with information or immured in ‘hyperreality’ that events communicated via the mass media no longer have such a visceral impact? The fact that the daily news programs continuously transmits bad news suggests otherwise. It also suggests that they are responding to a very directly emotional proclivity. Psychologists talk of a ‘negativity bias’ which makes us tend to see things in a detrimental light, while evolutionary psychologists suggest that this tendency derives from the time long ago when it was safer to expect a cave bear is lurking in the darkness of a cave rather than rush on in out of the cold.

We are the ancestors of people who erred on the negative appraisal of situations and thereby survived. But what thinking about my dual ‘epiphanies’ leads me to conclude is that we also have a ‘positivity bias’; we are also hardwired for the experience of emotional elevation, ecstasy and joy. And this means we are the descendants of humans with a pronounced capacity for such positive emotions, too. This is quite an emotional payload!

Image and Text Sources:

Itaewon photo: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2022/11/281_339362.html

https://www.theravada.gr/en/about-buddhism/the-four-noble-truths/

SongChol, Opening the Eyes, translated by Brian Barry, Seoul: Gimm-Young International, 2004, pp.122-123

Acorn for Dinner!

In a previous post I mentioned that here in Korea, eating acorns is still popular. They usually use powdered acorn to make a jelly called Dotori-muk. This weekend, my partner, Eungbok, made some Dotori-muk with flour she purchased from a chef colleague who gathers the acorns herself around where she lives in south Seoul.

In a previous post I mentioned that here in Korea, eating acorns is still popular. They usually use powdered acorn to make a jelly called Dotori-muk. This weekend, my partner, Eungbok, made some Dotori-muk with flour she purchased from a chef colleague who gathers the acorns herself around where she lives in south Seoul. Here’s what the flour looks like:

And here’s the jelly, which looks a bit like brown tofu:

Eungok mixed the flour with water, and with sesame oil to give it consistency. The flavour? I have to admit Dotori-muk doesn’t really have any. But the jelly-like texture is very pleasant. Anyway, Dotori-muk is usually served with a seasoning sauce or in a soup flavoured with radish and seaweed, which is how we ate it. It’s packed with goodness. Acorns are very nutritious and filling, while not containing fat, cholesterol, or sodium. Its health benefits include being an antioxidant, and it’s good for stomach ailments, helping in the promotion of healthy gut bacteria.

The species of oak that are preferred here to make flour are Quercus dentata and Quercus mongolica, whose acorns have less tannin than other oaks. The acorn of Quercus mongolica, aka the Mongolian oak, has a cup somewhat like those of the familiar European oaks but is more bumpy - more rugged, one could say. Quercus dentata, aka Korean oak, Japanese emperor oak, daimyo oak, or sweet oak, has a hugely hairy cup, so this one is very unlike those I’m familiar with from Europe. Like this:

Once upon a time, wherever there were oaks and human beings acorns were a stapple of the latter’s diet. As David A. Bainbridge writes in a fascinating essay entitled ‘Acorns as Food’ which I found on the Internet :

They occur in the archaeological record of the early town sites in the Zagros Mountains, at Catal Hüyük (6000 BC), and oak trees were carefully inventoried by the Assyrians during the reign of Sargon II. They have been used as food for thousands of years virtually everywhere oak trees are found. In Europe, Asia, North Africa, the Mid-East, and North America, acorns were once a staple food.

They were a staple food for people in many areas of the world until recently and are still a commercial food crop in several countries. The Ch'i Min Yao Shu, a Chinese agricultural text from the sixth century recommends Quercus mongolica as a nut tree. ……..

While it is often thought that oaks were a "wild crop" it is now clear that the oaks were planted, transplanted, and intensively managed. Informants and traditional songs tell of the selection and planting of oak trees. The early travelers often remarked on the “orchard like" settings encountered. How surprised they would be to find they were indeed orchards.

But as agriculture supplanted hunting-and-gathering, grains such as wheat, oats and rice became central to the human diet, and the acorn was relegated to being fodder for animals, such as swine. In medieval Europe in the autumn, swine would be released to forage for acorns in the forests, but their human owners would only recourse to the nut of the oak in times of want and famine. In other regions of the world, however, such as in what became California, Europeans arriving in the nineteenth century found that native American tribes treated acorns as a vital part of their diet. Of the situation today, Bainbridge writes:

A large commercial harvest still occurs in China, and acorns are sold on the streets by acorn vendors. The commercial harvest in Korea (where 1-2.5 million liters are harvested each year) provides prepared acorn starch and flour that reaches the American markets. Some acorns are collected in Japan. Acorns are still harvested and used in several areas of the United States, most notably Southern Arizona and California. There is still some harvesting in Mexico. Historically acorns were particularly important in California. For many of the native Californians, acorns made up half of the diet and the annual harvest probably exceeded the current sweet corn harvest in the state.

Why did the acorn get demoted in many places? It’s true that it takes time and effort to make an oak nut edible. An acorn is full of tannin, and so needs to be leached with water. But as Bainbridge writes:

Studies at Dong-guk University in Seoul, South Korea showed the tannin level in one species of bitter acorns was reduced from 9% to 0.18% by leaching, without losing essential amino acids. Virtually all of the acorns the native Californians used were bitter and they were leached or soaked in water to remove the bitterness. They apparently based their preference on oil content, storability, and flavor rather than sweetness.

Perhaps after the agricultural ‘revolution’, acorns, like all the other nuts that were once foraged by hunter-gatherers, were on an unconscious level too deeply associated with more ‘primitive’ stages of social development, and so had to be relegated, lest they remind humanity of the price they had paid for becoming sedentary and toilers of the soil. After all, Jared Diamond calls the agricultural revolution “the worst mistake in the history of the human race.” Hunter-gatherers had a more varied diet, including fats, proteins and vitamins…..and acorns. Farmers’ diet were simpler and less diverse, and they were constantly at risk of crop failure……when they would revert to the time-honoured convention of eating acorns. Add to this the fact that sedentism vastly increased the likelihood of contracting communicable diseases, and the agricultural revolution does start to seem less than magnificent evidence of humanity’s ability to perpetually develop towards greater general prosperity and well-being.

And now that the next ‘revolution’ - the industrial - is proving far from an unalloyed success, too, there are sound reasons for re-adopting the acorn as part of our diet. As Bainbridge writes:

There is a growing recognition that tree crops can play an important role in sustainable food production. Trees can be grown with less annual disturbance of the agricultural ecosystem and their deep roots allow the trees to reach nutrients and moisture in the deep soil. Acorns are an excellent example of a grain that grows on trees. We must begin to consider these traditional crops that fit temperate and semi-arid climates rather than trying to change the environment to fit crops that require extensive inputs of fertilizer and water.

I also noted in my previous post a great TED Talk by Marcie Mayer the founder of Oakmeal, who certainly concurs with Bainbridge’s view on the future of the acorn as food. Here’s a link to the company’s website: https://www.oakmeal.com/

References:

David A. Bainbridge, ‘Acorns as Food. History, use, recipes, and bibliography’, Sierra Nature Prints, 2001.

https://www.academia.edu/3829415/Acorns_as_Food_Text_and_Bibliography

Authority v Liberty. The curious case of South Korea

What kind of cosset do you want?

In my last post, I mentioned the censorship I have experienced in relation to the Chinese translation of my book, Seven Keys to Modern Art. Last week, in my class here in Korea with mainland Chinese students I brought it up with as much subtlety as possible. In the class, I discussed sociological approaches to modern art. As I am using Seven Keys as a textbook, and between them the ten Chinese and one Korean students have the Korean, English, and Chinese versions, they could compare editions. I pointed out the gap in the Chinese version between Barbara Kruger and Bill Viola, which is where Xu Bing should be. He’s gone because in my discussion in the book I refer to his shocked response to the repression in Tiananmen Square, which is still very much taboo in mainland China.

The students seemed very surprised. But also understandably rather tight-lipped about the omission.

I taught them the word ‘censorship’.

*

In the same class I showed the diagram above. It’s a rather good way of tracking the difference between China and the West, but also the unique position of the Republic of Korea. The West lies at the bottom right: ‘Individual Liberty’. China is up at the top right: ‘Collective Authority’. Hence the censorship. South Korea is somewhere in between. It’s an experiment in ‘Collective Authority plus Individual Liberty’.

The way in which these societies dealt with Covid helps to illustrate the differences. With its ‘zero tolerance’ attitude, China applied from the start its ‘Collective Authority’ model to the crisis. The West, by contrast, adopted an ‘Individual Liberty’ approach. South Korea dealt with Covid by mixing the two.

At first, ‘Collective Authority’ seemed the best option for everyone. The East Asian countries, being more attuned to this model, were quick to respond by introducing the necessary measures. China went to lockdown. The Western nations panicked, because ‘Individual Liberty’ is so obviously inappropriate in such a crisis, and they too went for lockdowns as an extreme recourse. South Korea managed to avoid lockdown, by contrast, but also any extreme spread of the virus. This is because with its unusual blend of ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ it was able to steer a middle course, epitomised by the skilful tracking of cases and the strict implementation of individual quarantines.

But with the evolution of the virus into the Omicron variant, ‘Individual Liberty’ has proven, rather surprisingly, in the long run a more robust social structure for dealing with the pandemic. China is now castrating itself by still pursuing the impossible goal of zero covid, even imposing lockdown once again in Wuhan, where the whole thing started. Only a society founded on ‘Collective Authority’ could work this way, that is, could be so rigid and maladaptive. Meanwhile, South Korea has segued to a situation in which the pandemic is confidently under control but in which people are still wearing facemask, because of the ‘Collective Authority’ component of this society. But it seems to me that the West has careened too fast away from the disagreeable experience of imposed ‘Collective Authority’ back towards a dangerous level of maskless ‘Individual Liberty’.

In this context, the tragic events in Itaewon, Seoul, over this Halloween weekend can be interpreted as an unfortunate unintended consequence of South Korea unique social blend, or social experiment. Inevitably, ‘Collective Authority’ and ‘Individual Liberty’ exist in uneasy tension. South Koreans tolerate a – to Westerners - very high level of group control, but they are also primed by Western ideals of ‘Individual Liberty’. The result in this particular case was a massive feeling of release amongst the young after the restrictions imposed during the pandemic. But, ironically, their desire for individual liberty expressed itself in a very collective fashion!

Image source: http://factmyth.com/understanding-collectivism-and-individualism/

What’s going on in China?

My experience of being censored by the Chinese!

China’s been in the news because of the 20th Party Conference in Beijing at which Premier Xi Jinping guaranteed himself a third term in office. Like me, you must have been confused by the footage of the previous Premier, Hu Jintao being escorted rather forcibly away:

What’s going on? It reminded me of a similar moment in North Korea in 2013 when Jang Song-thaek was similarly very publicly removed from a meeting of the WPK Political Bureau:

Later it was announced that Jang had been executed. Will the same thing happen to Hu? Probably not. The Chinese Communist Party is more subtle. He’ll simply disappear from public view.

This is the way they do it in dictatorships, apparently! It’s important to show who’s boss.

As I noted in a previous post, the philosopher Karl Popper wisely observed that the benefit of democracy is not so much that people get to vote but that leaders get to be removed from power without risk of violence. The contrast to the UK at the moment is striking. We are certainly way more genuinely democratic in this sense than China and North Korea, and our leaders very evidently get removed from power. But our democracy is still obviously very flawed as we are obliged to watch charlatans taking it in turns to become Prime Minister in a risible game of musical chairs.

***

China is especially on my mind because a couple of my books are now in Chinese translations. Seven Keys to Modern Art, and The Simple Truth. The Monochrome in Modern Art. Here they are:

The mainland Chinese version.

The Taiwan Chinese version.

The Taiwan Chinese version of The Simple Truth.

Seven Keys was published by Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House in Beijing, while Seven Keys and The Simple Truth was published by Diancan Art and Collection Ltd. in Taipei, Taiwan. But I have only received copies (and recently) of the mainland Chinese version of Seven Keys, and can find almost nothing about the Taipei edition on English language Google. The Taipei publisher did a couple of weeks ago send me three copies of the recently published Chinese translation of The Simple Truth. But still no sign of their Seven Keys.

The fact that Seven Keys has been published in Chinese in both Taiwan and mainland China may seem a bit odd, and also surprising, because the English edition, published by Thames & Hudson, couldn’t be printed in China because one of the artists I discuss is Xu Bing, whose work is related to the Tienanmen Square protests in 1989. This is a taboo subject in the People’s Republic! So, I assumed at first that Party censorship has become relaxed enough to allow the unexpurgated publication of my book. But of course not! When I looked at the mainland Chinese version more closely I realize that there is now no chapter on Xu Bing!

This is ironic for me, because I am currently teaching (in English) a PHD class here in Korea made up of almost entirely of mainland Chinese students - about ten of them - plus one solitary Korean. I am using Seven Keys as a text book, so the students can choose between using English, two Chinese, or Korean translations. But I hadn't realized until very recently that the mainland Chinese version, which is the one for sale on Amazon (no sign there of the Taiwan version…) and the one several of the Chinese students have opted to purchase, that Xu Bing has been excised.

Image Sources:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/23/xi-jinping-chooses-yes-men-over-economic-growth-politburo-purge-china

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/23/xi-follows-maos-footsteps-puts-himself-at-core-of-chinas-government

https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_northkorea/614727.html

Acorns

I’ve been getting to know the oak tree. Turns out there are more kinds than I expected. Over 500, in fact. But in the UK and France there are basically just two indigenous species: the Pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) and the Sessile oak (Quercus petraea). Here in Korea, there are six indigenous species, and they are very different one from the other. Within just half a mile of our house we’ve identified five. Here are their acorn

This morning we woke up to the first frost of the season. But the temperature quickly rose, and as I write this at around 10.30am it’s already quite warm outside in the bright autumn sunshine.

I’ve been getting to know the oak tree. Turns out there are many more kinds than I expected. Over 500, in fact. But in the UK and France there are basically just two indigenous species: the Pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) and the Sessile oak (Quercus petraea), and they are almost identical – the difference lies most obviously in the fact that the former grows its acorns on stalks while the latter does not.

Here in Korea, there are six indigenous species, and they are very different one from the other. Within just half a mile of our house we’ve identified five. Here are their acorns:

This is how I’ve identified them: Top left: Korean oak (Quercus dentata). Top right: Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica). Bottom left: Sawtooth oak (Quercus acutissima). Bottom right: Oriental white oak (Quercus aliena). Bottom centre: Oriental white oak (Quercus aliena var. acutiserrata)…. Maybe.

The most common around here is the Oriental white oak, which also has acorns that are most like the ones I’m familiar with from England and France. But the most common nationwide are the Sawtooth and Mongolian oak.

Here’s a map showing distribution ratio within South Korea. Looks like we live in an area that’s more than 40% oak trees :

The Korean oak is my favourite, and it has really huge leaves. I took a photo with my hand superimposed to give some idea of just how big:

Over the past couple of weeks locals have been out collecting acorns because they are used to make a nutritious jelly – Dortori-muk. When I did a bit of research about acorns as a food, I came across this fascinating TED Talk by an American woman Marcia Meyer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vi-1s1Bjs4

The Geese have arrived (earlier)!

I have noted the arrival of the geese in a couple of previous posts. This year, they arrived about a week earlier than last year – in the last week of September. Why?

I have noted the arrival of the geese in a couple of previous posts (Oct.1 2019 and Oct.7 2020). This year, they arrived about a week earlier than last year – in the last week of September. Eventually, thousands of bean geese (Anser fabalis) winter around here, having come from their breeding grounds in Mongolia and thereabouts. Apparently, the FAD (First arrival dates), as it is technically called, has been getting earlier and earlier due to global warming. The authors of an article in the Journal of Ecology and Environment wrote back in 2018: ‘Average temperature of September in wintering grounds has increased, and the FADs of the geese have advanced over the 22 years. Even when the influence of autumn temperature was statistically controlled for, the FADs of the geese have significantly advanced. This suggests that warming has hastened the completion of breeding, which speeded up the arrival of the geese at the wintering grounds.’ (1)

I always find it reassuringly ironic that the geese have to fly over North Korea and the DMZ to get to us. In other words, for them, there is no divided Korea. There is no Korea, North or South, just breeding grounds and wintering grounds. Adopting a ‘bird’s eye view’ in this context helps to put human history in tragic and absurd perspective. But it also drives a deep wedge between the natural history that addresses the lives of the geese and the human history about the lives of North and South Koreans.

This year, the geese’s arrival coincided with my reading of Dipesh Chakrabarty’s excellent The Climate of History in a Planetary Age (2021). His book added an additional significance to the event. The annual rhythm of bird migration serves to reinforce the assumption that nature as a whole is permanently cyclical. But now that we’re in the Anthropocene we are becoming aware that while nature has clear repetitive cycles based on the changing seasons, these are far from eternal. They just seem that way because of our very limited sense of historical time. Geological time, which deals in millions of years, reveal that massive changes occur in nature, sometimes absolutely devastating changes.

But humanly-caused global warming is now happening at such an alarming rate that, as the geese’s migratory pattern demonstrate, nature’s rythmns are changing within our timescale, and are easy to recognize. As a result, Chakrabarty writes that it is now essential that we find ways to conjoin the facts of Natural History with those of Human History. Climate scientists are showing that we can no longer treat them as distinct domains: “In unwittingly destroying the artificial but time-honoured distinction between natural and human histories, climate scientists posit that the human being has become something much larger than the simple biological agent that he or she always has been. Humans now wield a geological force……. A fundamental assumption of Western (and now universal) political thought has come undone in this crisis.”

References:

https://jecoenv.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41610-018-0091-2

Dipesh Chakrabarty’s The Climate of History in a Planetary Age is published by Chicago University Press.

North Korea’s Victory over Covid-19

So, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea did not collapse due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Why?

So, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea did not collapse due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This is what the excellent website 38 North said on August 15 :

‘Despite widespread concern that a COVID-19 outbreak in North Korea would be devastating, given the country’s weak health care system, limited access to medical equipment, supplies and medicines, and widespread malnutrition, Pyongyang appears to have stabilized the recent outbreak in record time with minimal deaths, at least according to the official government narrative. While North Korea seems to have avoided drastic outcomes this time around, its anti-epidemic efforts came at high economic and social costs, and the largely unvaccinated population remains a concern to global efforts to combat this virus. Building the country’s capacity to deal with epidemics and health crises should be part of a global health strategy to prepare for future pandemics.’ (1)

Of course, we are used to not taking anything North Korea says at face value. Officially, they say that on July 29, 2022, the number of what are called euphemistically ‘fever cases’ reached zero. Almost 20 percent of the population fell ill, but the number of deaths was only 74, a case-fatality rate of 0.0016 percent. As all the experts point out, this is impossible. The lowest country for case-fatalities is Bhutan at 0.035 percent. Other countries with vaccination rates above 80 percent, such as Singapore, South Korea and New Zealand, reported 0.1 percent.

But whatever the actual numbers, even the most hawkish critics of North Korea accept that the crisis was handled. The regime did not topple. Life (such as it is) goes on.

So, why? 38 North offers some answers:

‘North Korea’s health care system is founded primarily on preventative medicine, making disease monitoring and prevention the priority. As such, during the COVID-19 outbreak, local doctors and medical students were tasked with visiting 200-300 homes per day to facilitate disease surveillance.

Based on state media reporting about the pandemic responses, it appears that the North Korean government’s stewardship of the response to the outbreak has been effective and efficient. They declared a national emergency immediately after the first confirmed COVID-19 case, ordered a nationwide lockdown, and delivered medicine and food to houses while promoting the production of domestic medicine. State media has also reported the case numbers and provided medical information about COVID-19 daily.

With limited geographic mobility and domestic migration even before the pandemic, North Korean society is set up in a way that makes controlling the transmission of this airborne virus easier than in most countries. In short, North Korea was able to quickly stop community spread through aggressive public health measures, and as such, has not experienced a catastrophic situation. Furthermore, the first reported COVID-19 case was said to have been of the Omicron variant, which while more contagious, is less severe than the original virus or other variants.’

What this prognosis boils down is an interesting fact: the least ‘open’ society in the world proved to be one of the best at dealing with the pandemic, while the most ‘open’ societies proved the worst.

In his book Open. The Story of Human Progress (2020), Johan Norberg writes that ‘openness’ is inextricably tied to globalization: ‘Present day globalization is nothing but the extension of…. cooperation across borders, all over the world, making it possible for far more people than ever to make use o the ideas and work for others, no matter where they are on the planet. This has made the modern global economy possible, which has liberated almost 130,000 people from poverty every day for the last twenty-five years.’ Norberg also notes that ‘when China was most open it led the world in wealth, science and technology, but by shutting its ports and minds to the world five hundred years ago, the planet’s richest country soon became one of the poorest.’ Nowadays, however, China has sufficiently opened up to globalization to become prosperous again.

North Korea is an obvious example of what happens when a country is ‘closed.’ Interestingly, on this level it follows the policy of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897) whose isolation earned Korea the named ‘The Hermit Kingdom’, and also made it a ripe pickings for Japanese colonial ambition in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-centuries. Japan, of course, did ‘open’ up – it was the first of the East Asian nations to do so, and the first to colonize another East Asian country (Korea in 1910) and to defeat a western power (in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05) . In this sense then, North Korea is a reversion to a former societal model, whereas South Korea, who has aggressively joined the ‘open’ global market, is following themodel first pioneered by its neighbor and former colonial master, Japan. It is obvious in pretty much all terms which of the Koreas chose the better path.

*

But the ‘openness’ of globalization is precisely what allowed the pandemic to happen. This is a fact that North Korea’s success highlights. The downside of ‘openness’ is porosity of borders. As Jared Diamond points out in his classic Guns, Germs, and Steel. The Fates of Human Societies (1997): ‘The rapid spread of microbes, and the rapid course of symptoms, mean that everybody in a local human population is quickly infected and soon thereafter is either dead or else recovered and immune. No one is left alive who could still be infected. But since the microbe can’t survive except in the bodies of living people the disease dies out, until a new crop of babies reaches the susceptible age – and until an infectious person arrives from the outside to start a new epidemic.’ (Emphasis added) The classic historical case of this viral invasion is the virtual annihilation of the indigenous peoples of north, central and south America by ‘white’ settlers who brought their infectious diseases with them – diseases for whom they had developed immunity but the indigenous people , having never been exposed to them, had not. Diamond gives several examples. Here’s one that is harrowing in its definitiveness: ‘In the winter of 1902 a dysentery epidemic brought by a sailor on the whaling ship Active killed 51 out of the 56 Sadlermiut Eskimos, a very isolated band of people living on Southampton Island in the Canadian Arctic.’

An ‘open’ society is bound to be prone to epidemics, while a ‘closed’ one is more likely to be able to control them. But it is also much more dangerously vulnerable if (indeed, when) the closed gate is breached. This vulnerability explains why a ‘closed’ society will desperately fight to keep the gate closed. But it also explains why they are doomed to fail.

Living in societies that value ‘openness’ is not just about markets, however. It’s also about ‘openness’ to worldviews, beliefs and behaviour, and this means a society will also be vulnerable to cultural ‘infection’. An ‘open’ society is perpetually being ‘infected’ by alien worldviews, and this inevitably causes tensions, and possibly conflicts. But as time goes by, the people of an ‘open’ society develop ‘immunity’ to these novel cultural pathogens. This is clearly what has happened as western societies have become more tolerantly multicultural. But the onslaught is continuous, and inevitably unsettling. Meanwhile, in a ’closed’ society like North Korea – in fact North Korea could be described as the archetype of a ‘closed’ society – cultural pathogens are not an immediate danger. They lie safely beyond the closed gate – in South Korea, America, Japan - but the dangers they potentially pose can be used to install fear in the populace.

Interestingly, the North Koreans claim that the Covid-19 virus entered their land via ‘alien objects’ found on a hillside. They elaborated by saying that these ‘objects’ came via balloons from Korea (the South Koreans have banned the sending of propaganda via balloons across the DMZ, but it still happens). Much more likely is that the disease entered via illegal trading with China.

In other words, total closure of a society is impossible. It always has been, as humans are hard-wired to trade. Where societies are concerned, there’s no such thing as totally water-tight barrel. They will always be leaky. Which is why an ‘open’ society is an inevitable advance on a ‘closed’ one. But this is especially true in an era of technologies that allow for ease and speed of travel. In earlier times, when people could only travel by foot, horse, horse and cart, or by sail across the oceans, being ’closed’ seemed a viable option. Today it obviously is not.

So, even though North Korea stamped put Covid-19 with remarkable success, it is surely still doomed.

Image source: https://www.ft.com/content/4f82c57b-fb10-4945-b6ab-df9445c57715

Masks….Yet Again.

I spent the summer in France, and it was quite a shock to suddenly be somewhere in which wearing facemasks was no longer mandatory in public places, as it still very much is in Korea. I am also back in the classroom teaching students face-to-face, or mask-to-mask. I am finding it a terribly demoralizing experience. The masks of my student make it difficult to recognize them, but even more awful, completely erases one of the most important markers through which I can receive signals of a student’s active engagement with my teaching – their mouths. This post incloves some more reflections on cultural difference as revealed through the protocols of wearing facemasks.

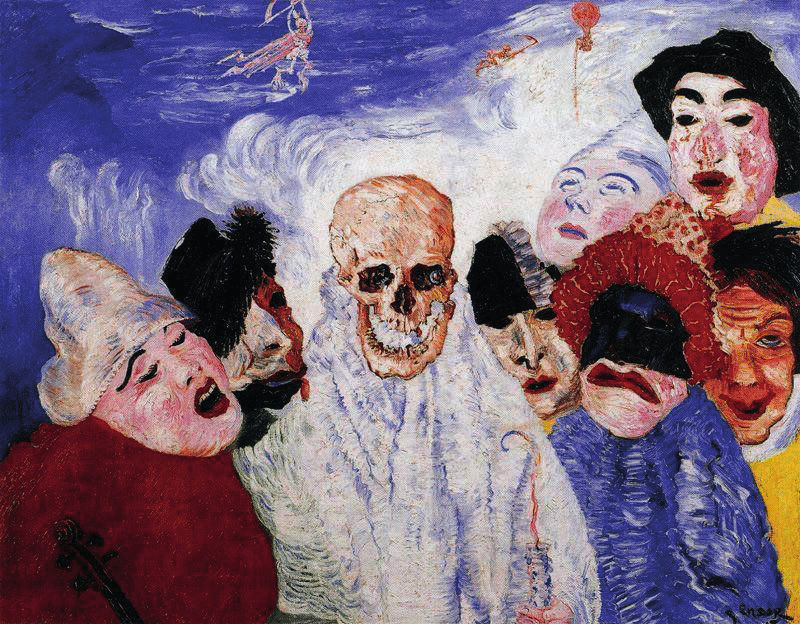

James Ensor, Death and the Masks (1897). Source: https://www.artforum.com/print/previews/201007/james-ensor-26245I apologize for once again writing about damn face-masks. But as I mentioned a couple of posts ago, I spent the summer in France, and it was quite a shock to suddenly be somewhere in which wearing face-masks was no longer mandatory in public places - as they still very much are in Korea. I am also back in the classroom teaching students face-to-face, or rather, mask-to-mask, and I’m finding it a terribly demoralizing experience. The mask makes it difficult to recognize my students, but even more awful, completely erases one of the most important markers through which I receive signals of their active engagement with my teaching: their mouths.

Inevitably, this has got me thinking about the face-mask again as a sign of cultural difference, and why it is that Korean society finds it so much less onerous to wear them than do westerners. Why are the latter willing to take more risks with their own and others’ well-being than Koreans? Why is the calculus of relative pros and cons so different? In particular, I have got thinking about the trade-off between public health safety assessed in terms of viral infectiousness and social solidarity, as exemplified by Korea, and public health safety assessed more (and mostly unconsciously, I think) in terms of psychological well-being, humaneness, and the values associated with sociality and freedom, as exemplified by the west.

By now, I’ve read several psychological and medical reports about face-masks. I’ve found that while the physical health benefits are pretty much agreed on there is less consensus concerning their potential psychological toll. Are children being permanently or even temporarily mentally affected in negative ways by having to wear masks? To what extent is people’s capacity for empathy being temporarily or permanently obstructed? Are we being turned into abnormal or even sociopathologically solipsistic automatons?

My classroom of masked students is bad enough, but it is hard to conjure up a more visually graphic image of psychological social alienation than a subway carriage of Koreans bent over their smartphones and wearing masks (see my post from May 24th, 2022 for another take on the effect of smartphones in such situations). It also seems an especially powerful image of baleful subjugation and conformity. I can’t help but see the combination of face-mask and smartphone as constituting a socially and politically useful way of pacifying people, and also without any obvious coercion, as they are ‘self-medicating’ by apparent choice. The passengers are tranquilizing themselves by drastically narrowing their potential interactions with the immediate environment.

This is, to be sure, an environment that possesses a great number of visual, aural, olfactory and tactile stimuli that are likely to make any half-normal person feel uncomfortable, bored, or downright threatened, and that are not in any stretch of the imagination attractive, pleasant or benign. The mask aids and abets the healthy quest for secure environmental buffering. It is an excellent means of hiding oneself from the gaze of a disagreeable world. I don’t just mean the gaze of other people, but more metaphorically, the ‘gaze’ of one’s surroundings - the call to us made by these surroundings. of spaces with which we are actively connected and with which we instinctively expect to be able to respond resonantly.

The face-mask is a way of ensuring that one remains distant, detached, and disengaged. But in the subway the masking of the face is combined with the lowering of the head and the directing of the gaze towards a small illuminated rectangular screen. As I have discussed in a previous past, this dramatically limits access to the expansiveness of the visual field which the human eye has evolved to see. It produces a kind of tunnel vision, and, as the term in popular usage implies, involves a narrowing and impoverishing of vision. But the smartphone makes this seemingly detrimental action alluring because it substitutes the unpredictable, threatening, ugly, actual surroundings for surroundings over which one has complete control, that via the magic of the Internet offer potentially resonant relationships to the world rather than alienating ones. This is a very attractive trade-off, and no wonder everyone is eager to make it. We transports ourselves from the disagreeable place where our bodies are located in real time and space to another space replete with much more appealing stimuli.

A subway system anywhere in the world is never going to be a very appealing and enlivening environment, especially in the rush-hour. It’s inherently awful, really. No one in their right mind would choose to be there. But of course, we all ride the subway because we need to get to work or want to meet our friends. Like so much of modern city life, the environment through which we habitually move is an inherently alienating one. Not so much a concrete jungle as a concrete desert. The casting down of the gaze and the focusing of attention on a small illuminated screen, plus the concealing of the nose and mouth behind a mask are therefore highly efficient ways of blocking or buffering contact with one’s immediate surroundings and achieving a relatively robust form of autonomy and control. But obviously, these benefits come at a dreadfully high price.

*

I used the word ‘buffering’ above in knowing reference to the writings of the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, who juxtaposes the terms ‘buffered’ self with ‘porous’ self in order to make a basic distinction between the modern and pre-modern conceptions of identity within European society. The ‘porous’ self is an earlier model of human relationship to the world that characterized Europe prior to the seventeenth century. What Taylor describes as the uniquely modern ‘secular’ world is precisely a world in which relationship are no longer founded on ‘porosity’ of self but on the benefits accrued from the bounded of ‘buffered’ relationship of the self to the world.

Here is what Taylor says about the latter in A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007) : “As a bounded self I can see the boundary as a buffer, such that things beyond don’t need to ‘get to me’, to use the contemporary expression….This self can see itself as invulnerable, as a matter of the meaning of things for it.’ (p.38) A ‘buffered’ mode of existence “can form the ambition of disengaging from whatever is beyond the boundary, and of giving its own autonomous order to its life. The absence of fear can not just be enjoyed, but seen as an opportunity for self-control or self-direction.” (38-9) Thus, the ‘buffered’ self is characterized by a stance of disengagement from the world which is adopted because it accrues a “sense of freedom, control, invulnerability, and hence dignity”(285). Taylor notes that much of the value associated with this ‘buffered’ disengagement from the world has derived from the way in which it mirrors on the level of personal existence “the most prestigious and impressive epistemic activity of modern civilization, vz., natural science” (p.285), that is to say, the rational or objective point of view.

By contrast, there is the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. Here, “the boundary between agents and forces is fuzzy……[T]he boundary between mind and world is porous” (39). The relationship to the world is also what Taylor calls “enchanted”, by which he means that because there is no firm boundary between self and world, one feels intimately affected by the world in ways that continuously open one up to uncontrollable an mysterious forces. There is no clear distinction between the subjective and the objective, the interior world and the exterior.

In his study, Taylor is limiting his analysis to the western world, but it seems to me that his concept of ‘porous’ and ‘buffered’ selves can be extended to global proportions (with obvious caveats). It seems especially interesting in relation to cultures that have experiences rapid modernization under the aegis of western ways of thinking, and therefore have evolved rapidly from societies based on the ‘porous’ self to ones based on the ‘buffered’ self.

So, back to the Seoul subway carriage. Is it too much to suggest that the uniform behaviour of the Korean passengers of all ages (except the very old, who are not accustomed to smartphones!) can at least in part be understood by recognizing that they are living in a culture that has metamorphosized from one dominated by the pre-modern ‘porous’ self to one increasingly dominated by the benefits accrued by being a bounded, disengaged ‘buffered’ self - a self that makes one a fully-fledged ‘modern’ person? But the speed of change means that the characteristics of the ‘porous’ and the ‘buffered’ self co-exist in unique ways in Korea. For example, the high level of conformity manifest in Korean society is a clear reflection of a core characteristic or the pre-modern ‘porous’ self. As Taylor writes of European culture: “Living in the enchanted, porous world of our ancestors was inherently living socially. It was not just that the spiritual forces which impinged on me often emanated from people around me……Much more fundamental, these forces impinged on us as a society, and were defended against by us as a society……So we’re all in this together.” (42) Taylor’s words made me think of the collective reaction within Korea to Covid-19, and how they contrast to the western response, which was far more based on a ‘buffered’ sense of self in which individual autonomy has priority of the social sense of all being “in this together.” As Taylor adds, as a result of the pressure to subordinate self to group, in a society ruled by a sense of the ‘porous’ self there will be a “great pressure towards orthodoxy.” (42) But in contrast to this impulse, one can also very clearly observe in modern-day Korea other forces that derive from the adoption of the new bounded, ‘buffered’ sense of self, which prioritizes disengagement as a source of self-efficacy. As a result, , in the Seoul subway carriage we find the melding within the same person of characteristics of ‘porosity’ and of ‘buffering’ in relation to the self, of collective behaviour and disengagement.

Has the speed of social transformation been fundamentally traumatizing for Koreans? Are the visible exterior signs (the persistent mask, the obsessive zoning in on the cellphone screen) the manifested signs of an interior mental state that is, in a sense, a kind of mental and social derangement?

Social Bonding

As soon as I saw all the barn swallows all lined up along the electrical wire near my house in Korea I thought of the lines of people waiting to pay their respects to the recently departed queen of Great Britain and Commonwealth. A friend in London had sent me pictures of her all-night vigil at the Palace of Westminster, and it was clearly a powerful experience for her, above all, one that gave her a profoundly meaningful feeling of belonging, of bonding with others and with her heritage. As she wrote: “the Queen was extraordinarily in our lives.” Today’s post ruminates on the importance of social bonding in relation to the cultural anthropologist Victor Turner’s ideas about structure and anti-structure and society.

This morning I saw about a hundred barn swallows lined up along the same electrical cable near our village. Occasionally, they swooped away across the rice fields for a short time before returning to the line again. These swallows are doing some socializing before departure for far away southeast Asia. By socializing, they are also bonding, strengthening ties and group coordination that will be vital for surviving the epic journey ahead. This is what the RSPB says on its website: “Swallows migrate during daylight, flying quite low and covering about 320 km (200 miles) each day. At night they roost in huge flocks in reed-beds at traditional stopover spots. Since swallows feed entirely on flying insects, they don’t need to fatten up before leaving, but can snap up their food along the way. Nonetheless, many die of starvation. If they survive, they can live for up to sixteen years.” (1) Usually, a pair of barn swallows nests under the eves of our house, but this year a pair of Red-rumped swallows set up home. Here they are:

But for some reason, after strenuously adapting the barn swallows’ nest to their own specifications (they prefer a tunnel entrance), in July the pair of Red-rumped swallows abandoned their finished nest and were never seen again.

*

As soon as I saw the swallows all lined up along the wire I thought of the lines of people waiting to pay their respects to the recently departed queen of Great Britain and Commonwealth. A friend in London had sent me pictures of her all-night vigil at the Palace of Westminster, and it was clearly a powerful experience for her, above all, one that gave her a profoundly meaningful feeling of belonging, of bonding with others and with her heritage. As she wrote: “the Queen was extraordinarily in our lives.”

It’s odd being so far away, so very much on the outside, although I too felt the news of the queen’s death as something very significant, and will probably be deeply moved by the funeral on Monday 19th. As everyone my age (and quite a bit older) keep saying: “she’s been there all my life!”

But I’m not here going to add my thoughts to the mountain of views on the British monarchy or the queen. Instead, I want to think about the psycho-social mechanisms involved in the kind of bonding ritual in which my friend, like so many others, is choosing to be involved right now. Why is it so important?

The word ‘ritual’ is not one that has a very good press these days. It tends to be associated with religion, with convention and outdated behaviour. There’s not much place for ritual in our fast-paced, technological society. But that’s precisely the problem. As the British cultural anthropologist Victor Turner argued The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (1969), the ‘ritual process’ is vital for the secure and healthy maintenance of any society, which he defined in terms of a binary tension between structure and anti-structure, modes of organization which together are the two major ‘models’ for human interrelatedness. The former refers to a differentiated and usually hierarchical social system that separates people into positions of ‘more’ or ‘less’, and thereby ensures security and stability across time. But that is only one kind of society. Turner juxtaposed this ideal with another that embraces anti-structure, “an unstructured or rudimentarily structured and relatively undifferentiated comitatus, community, or even communion of equal individuals who submit together to the general authority of the ritual elders.” (1969, p.96) As he explained:

Society….is a process in which any living, relatively well-bonded human group alternates between fixed and – to borrow a term from our Japanese friends – ‘floating worlds.’ By verbal and nonverbal means of classification we impose upon ourselves innumerable constraints and boundaries to keep chaos at bay, but often at the cost of failing to make discoveries and inventions…….[I]n order to live, to breathe, to generate novelty, human beings have had to create – by structural means - spaces and times in the calendar or in the cultural cycles of their most cherished groups which cannot be captured in the classificatory nets of their quotidian, routinized spheres of action. (p.vii)

Turner adopted the Latin term communitas in order to describe this idea of society as anti-structure, and the term ‘liminal’ to evoke the antistructural experience within the ritual process in order to describe the ‘in-betweenness’ or transitiveness of their state necessary for the deep bonding that antistructure facilitated. As Turner writes, this is a model of society “as a homogeneous, unstructured communitas, whose boundaries are ideally coterminous with those of the human species.” (p.136)

A 1996 reprint of Turner’s classic text from 1969 published by Routledge: https://www.routledge.com/The-Ritual-Process-Structure-and-Anti-Structure/Turner-Abrahams-Harris/p/book/9780202011905

The problem with any society based on structure is that it separates and hierarchizes into discrete parts and systems, making the desire and natural ability to intimately bond between individuals and across groups very attenuated, and therefore radically diminishes and circumscribes the potential richness of human relationships to each other and the world. In our society, bonding is almost only something that happens on an individual or small group level – between lovers, members of the family, supporters of the same football team. Children are better at bonding than adults because they are less structured psychologically. Indeed, the more a society embraces structure the more atomized bonding becomes. But we all crave to bond as expansively as possible, to experience communitas, and so societies develop ways through which to incorporate the experience of antistructure which is the prerequisite for collective bonding into its rituals. In his study of Ndembu ritual Turner described the African tribe’s complex manner of working through the dual impulses of structure and antistructure within elaborate ritual activity, but he also referred to modern western conventions, and especially drew attention to such rituals as carnivals and other socially sanctioned rituals such as football matches or rock concerts in which the antistructural or liminality can be experienced.

But as Turner stresses the immediacy and authenticity of ‘existential communitas’ cannot be endured for long by society. “[T]he spontaneity and immediacy of communitas – as opposed to the jural-political character of structure – can seldom be maintained for very long. Communitas itself soon develops a structure, in which free-relationships between individuals become converted into norm-governed relationships between social personae’ This is what Turner calls ‘normative communitas’, “where, under the influence of time, the need to stabilize and organize resources, and the necessity for social control among the members of the group in pursuance of these goals, the existential communitas is organized into a perduring social system.” (p.132) It is also a feature of any society that the powers vested in the maintenance of social structure will attempt to appropriate the energies of communitas, of antistructure, in order to maintain and strengthen their position. They will manufacture rituals that offer a modicum of the experience without any risk of the energies released spilling over into potential anarchic anti-social behaviour.

North Korea is a good example of a political elite organizing society around elaborate rituals that blend structure and antistructure in order to guarantee the stability of their status quo. But here we witness more than just a ‘normative’ use of communitas. Rather, the North Korea elite propagates a version of what Turner terms ‘ideological communitas’, in that it has adopted a rigid utopian model of society based on the fundamental yearning for ‘existential communitas’, which it then exploits in order to maintain power.

Modern techno-scientific society based on instrumental reason is dangerously deficient in antistructural rituals. And when they exist – especially within youth culture – they tend to be insufficiently linked dialectically to structure, and risk failing to pass the vital energy of communitas back into society at large. As a result, adult life is often characterized by a nostalgic longing for the antistructural experiences that characterize youth because such experiences are unavailable to the adult world.

But the British Royal family is an excellent source of ritual processes. One could say that it presents to the world the caricatured image of society as structure, of society as a series of rituals organized to maintain structure. As such, it acts is a mirror in which society at large can see both the virtues and the vices of living deeply within structure, with the “innumerable constraints and boundaries to keep chaos at bay.” This is precisely what the queen and the new king call ‘duty’. But the royal family also provides moments when the people can experience tame or ‘normative’ forms of communitas: during the rituals surround the funeral of the queen, for instance. These ‘normative’ forms provide the opportunity for deep and expansive social bonding, the experience of non-hierarchical oneness, while at the same time re-affirming the pre-eminent need for structural hierarchy. I suppose one could argue that, anthropologically speaking, the continuing significance of the Royals for us moderns, whose lives are starved of ritual, is to offer the experience of both structured and normatively liminal or unstructured relationships to the world (in small and well targeted doses). In the light of the dire straits in which Britain finds itself, its people certainly need generous doses of both.

NOTES

(1) https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/natures-home-magazine/birds-and-wildlife-articles/migration/migratory-bird-stories/swallow-migration/ Here is a great link to an article about how the swallow’s ‘disappearance’ in the winter has been explained historically: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/natural-histories/great-migration-mystery

Holding Heritage to Account

In today’s blog I include the second part of my talk for the International Conference on World Heritage, which was held in Korea in early September. The overall title was ‘World Heritage. Old Newness’, and my talk was entitled ‘Cultural Heritage as ‘Memory Event. The Case of Dansaekhwa’. In this second part, I widen the focus of my reflections to consider the crisis in the idea of ‘heritage’ in the West, and how it might relate to the idea of heritage in Korea.

In today’s blog I include the second part of my talk for the International Conference on World Heritage, which was held in Korea in early September. The overall title was ‘World Heritage. Old Newness’, and my talk was entitled ‘Cultural Heritage as ‘Memory Event. The Case of Dansaekhwa’. In this second part, I widen the focus of my reflections to consider the crisis in the idea of ‘heritage’ in the West, and how it might relate to the idea of heritage in Korea.

In my country, Great Britain, heritage is big business. We use the term ‘heritage industry’ a lot. In fact, it’s been argued that the entire island is one great ‘heritage’ theme park. Here’s an example of some of my heritage from near where I grew up in East Sussex in the south of England:

This is Bodiam Castle, built between about 1380-85. It still looks in remarkably good condition, doesn’t it? The interior, however, is a gutted ruin. Bodiam Castle is now owned by the National Trust, which looks after around 300 properties, and also manages great swathes of the British landscape, like this, the series of chalk cliffs on the South Downs overlooking the English Channel known as the Seven Sisters, also near where I grew up:

In relation to the arts, the National Trust website proudly announces: “no other organisation conserves such a range of heritage locations with buildings, contents, gardens and settings intact, nor provides such extensive public access.” Recently, however, the Trust became another victim of the on-going and increasingly crazy culture wars. In 2020 it published a policy review paper that addressed its properties’historical relationships to the slave trade and colonialism. As the UK’s Guardian newspaper’s website reported on November 12th 2020, the review paper “explored how the proceeds of foreign conquest and the slavery economy built and furnished houses and properties, endowed the families who kept them, and in many ways helped to create the idyll of the country house. None of this is news to most people with a passing acquaintance with history, and the report made no solid recommendations beyond the formation of an advisory group and reiterating a commitment to communicating the histories of its properties in an inclusive manner.” (1)

But it caused quite a furore. People on the political right, in particular, saw the Trust’s apparently guilt-ridden questioning and pathetic attempts at atonement as reprehensible evidence that its “ leadership has been captured by elitist bourgeois liberals”, as a letter from a group of enraged Members of Parliament put it - by people who were “coloured by cultural Marxist dogma, colloquially known as the ‘woke agenda’.”

What this little scandal reveals is the fact that the idea of ‘heritage’ is in crisis, at least in the West. The Guardian article goes on to mention the academic Patrick Wright, author of the best-selling On Living in an Old Country who, writing in 1985, described the National Trust as having been created as a kind of “ethereal holding company for the spirit of the nation”. But he was critical of this ideal, and his special target was the Prime Minster of the time, Margaret Thatcher, and her efforts to co-opt a certain image of Britain to help maintain her hold on power. Today, post-Brexit and in the light of the so-called ‘woke agenda’, the issues Wright raised back then have become even more pressing. Take Chartwell, Winston Churchill’s family home, which is also not far from my hometown:

Chartwell’s historical associations with the slave trade made it one of the Trust’s targets. As The Guardian noted, within the concept of heritage places “are easily mythologised as Britain’s soul, places in which tradition and inheritance stand firm against the anonymising tides of modernity. They are places of fantasy, which help us imagine a rooted relationship to the land that feels safe and secure. As Wright pointed out, this makes the project of preserving them necessarily defensive, and one that doesn’t sit well with the practice of actual historical research – which contextualises, explains and asks uncomfortable questions.”

The issue pivots on the problem of inheritance. Who in the present decides what is worth celebrating in the past, and how can they be held to account? What can or should be politely ignored or forgotten, and what must be condemned? At its worst, ‘heritage’ is an anodyne way of referring to the ownership of the past by the powerful in the present, who use it to help consolidate their position through permitting those with little or no power to enjoy some of the nation’s patrimony on the weekend without upsetting the status quo, while also allowing them to avoid dealing with the kinds of moral qualms and ambiguities that characterize the rest of their lives. Of course, there are far more positive ways to describe heritage. For example, that it a social category dedicated to countering the alienating effects of modern existence through providing the possibility of resonant relationships to the past.

I’m not sure to what extent the Republic of Korea should be engaging in the kind of mea culpa correctional process now going on in the West. Should you also be actively exposing the extent to which, for example, many of your admired Confucian scholars condoned slavery and the brutal subordination of women? Or is the Republic of Korea at a different stage of cultural development, or developing on a significantly different path, and so introducing ‘Western’ principles of social justice would actually be a new form of cultural colonialism? The context for the celebration of Korean heritage today is the legacy of Japanese colonization, rapid westernization, and an ideologically divided people. These facts demand a unique attitude to heritage to which everyone should be sensitive. The situation is very different to Britain, whose heritage nests within a far more unbroken and triumphalist story, one that is now in dire need of revision. Perhaps in Korea, the cultural situation demands a rather less uncompromising and aggressive relationship to its heritage.

Then again, the universality of the principles of justice now being employed to judge the past seems unquestionable. Slavery, the subjugation of women, these do seem morally repugnant wherever you stand – at least, if you’re standing in an open society that Is dedicated to maximizing the possibilities of human flourishing, at least in principle. But do we want to be reminded of these dreadful things - the past’s legacy of cruelty and woe - every time we visit our nation’s’ heritage. Must we always say, as Walter Benjamin did as the Nazi’s closed in, ‘There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.’ Won’t it ruin our day out?

But it is in this context that artists could be very useful. Their ‘unofficial’ view on things may help to enliven heritage. They don’t shy away from the truth, but they’re also not (or should not be) hanging judges standing on the moral high ground and passing judgement. Through perceiving the present’s similarities and differences from the past in more than a reactionary and traditionalist sense, but also in taking more than a stance of hostile deconstruction and critique, artists can show how to resist institutional sclerosis.

Notes:

(1) (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/nov/12/national-trust-history-slavery?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other&fbclid=IwAR2Ar4xEPtJ17i7QHdZZnMS8lCbb48T6TsOL8nMqU7jwb4QOnvCM-dd8bbs)All images courtesy of the National Trust.

Images courtesy of the National Trust.

‘Old Newness’

A few days ago I gave a talk at an International Conference on World Heritage held in Korea. The title of the conference was ‘World Heritage. Old Newness.’ The two-day conference included a video address from Stephan Doempke, the Chair of World Heritage Watch in which, amongst other things, he discussed the damage of cultural sites in Ukraine: UNESCO has verified damage to 168 sites since 24 February.

My talk was in the section of the conference dedicated to ‘Artistic Interpretation of World Heritage and Creation of Future Heritage’. It was entitled ‘Cultural Heritage as ‘Memory Event. The Case of Dansaekhwa’, and I am posting the first part of the talk today in a slightly different version. Here, I discuss the Korean art tendency known as ‘Dansaekhwa’ (One-colour-painting), which emerged in the Republic of Korea in the 1970s - I have written about Dansaekhwa on more than one occasion in this blog, and also published several essays, and there’s a chapter on Dansaekhwa in my book ‘The Simple Truth. The Monochrome in Modern Art’ (2020). I discuss how the artists’ works can be seen to transform the rigid experience of Past and Present into a more personal and inward experience of Then and Now.

A few days ago I gave a talk at an International Conference on World Heritage held in Korea. The title of the conference was ‘World Heritage. Old Newness.’ The two-day conference included a video address from Stephan Doempke, the Chair of World Heritage Watch in which, amongst other things, he discussed the damage to cultural sites in Ukraine: since the war began on 24 February, UNESCO has verified damage to 168 sites.

My talk was in the section of the conference dedicated to ‘Artistic Interpretation of World Heritage and Creation of Future Heritage’, and was entitled ‘Cultural Heritage as ‘Memory Event’. The Case of Dansaekhwa’. I am posting the first part of the talk today in a slightly different version. I discuss the Korean art tendency known as ‘Dansaekhwa’ (One-colour-painting), which emerged in the Republic of Korea in the 1970s - I have written about Dansaekhwa on more than one occasion in this blog and also published several essays on various aspects of the tendency, and there’s a chapter on it in my book ‘The Simple Truth. The Monochrome in Modern Art’ (2020). In this talk I discuss how these Korean artists’ works can be seen to transform the rigid experience of Past and Present into a more personal and inward experience of Then and Now.

First if all, here are examples of works by some Dansaekhwa artists:

Park Seo-Bo, Ecriture No, 28-73, 1873, Pencil and Oil on Canvas, 194.0 x 130.0 cm. Courtesy Kukje Gallery, Seoul.

Yun Hyong-keun. Umber, 1988-1989. Oil on linen, 205 x 333.5 cm. Courtesy of Yun Seong-ryeol and PKM Gallery, Seoul

Chung Sang-Hwa (1932-), Untitled 75-10, 1975, acrylic on canvas, 161x130cm. Courtesy Hyundai Gallery, Seoul.

Installation shot of works by Lee Ufan from the 1970s at Kukje Gallery, Seoul.

‘Cultural Heritage as ‘Memory Event. The Case of Dansaekhwa.’

By ‘memory event’ I mean a recollection of a specific occurrence which includes vivid details for the one doing the recollecting. It implies a ‘momentary’ sense of time, a temporal experience in which the linear chain between before and after is broken, and a moment drops out of its historical connection with other moments and gets a significance of its own. A ‘memory event’ overcomes the sterile binary of ‘past’ and ‘present’, substituting instead the potential for synthesis. One re-imagines the experience of history as something partially freed from linear order and objective causal succession. The Past and Present become the ‘Then’ and ‘Now’, a more personal and less rigid relationship to time.

The term ‘memory event’ fits very well the relationship to history evident in Dansaekhwa artists’ works. They blended an interest in Western modern art with what they consider important aspects of their own indigenous culture that are conducive to expression through monochromatic painting. In particular, they emphasize the tangible - the physical and sometimes laboriously repetitious working of a painting’s surface - and they engage more than the sense of sight by including touch and movement as part of the encounter. Dansaekhwa artists were motivated by the desire to unite or bring into alignment their bodies and their work in order to bridge the gap between the mental and the physical, the inside and outside. For them, a painting becomes as a living intermediary between the self and the world.

The cultural background to their intention is the artists’ attachment to pre-modern, pre-Western cultural ideals, which they sought ways to re-imagine for modern day Korea. This was possible because of the awareness of history as the perpetual coming into existence, developing, decaying and going out of existence of all things. Rather than the Western idea of progress, their relationship to time was more characteristic of what has been called the East Asian “‘Tao’ of history “, a relationship with which Dansaekhwa artists were intuitively associated. This meant attuning to alternation: to repeated occurrences in space and time and involved bringing together ideas and things across time and place. It characterized relationships to the past in terms of what is meaningful from the perspective of the individual constructing the connection in the present. In this temporal model, time is experienced as non-linear, dissolving, diaphanous, and ephemeral. It is something that can only be perceived, measured and remembered through an individual’s actions. As a result, history is conceptualized as a situation with potential in the present, something to be used to advantage in the now.