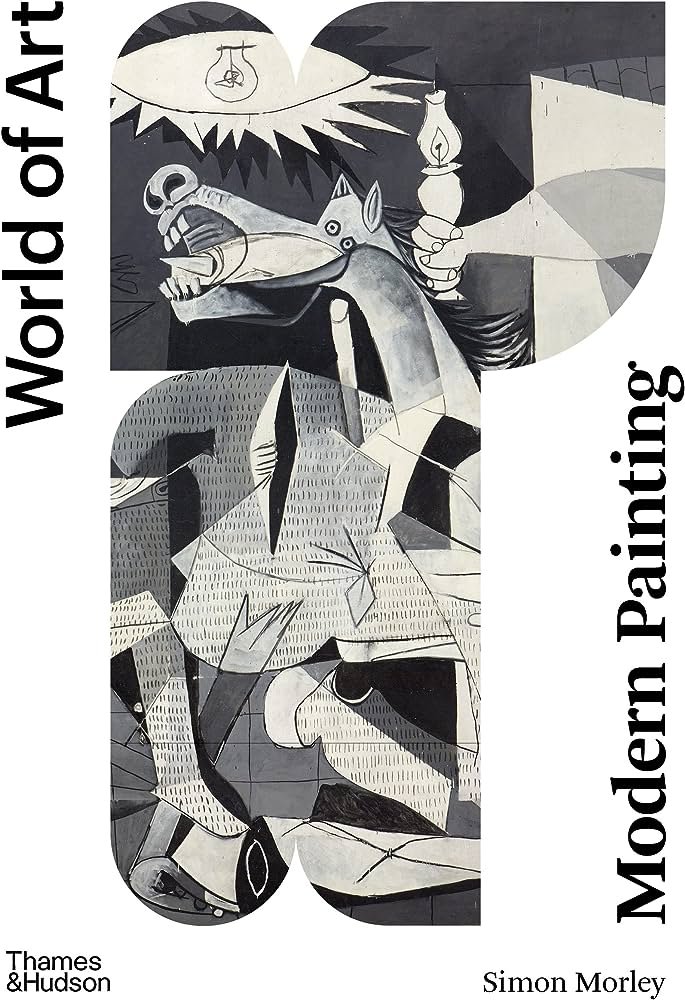

Just published ‘Modern Painting’!

My new book is just published by Thames & Hudson.

I’m back in Korea, and finally over jetlag. Waiting for me when I got home were the author copies of my new book: Modern painting. A Concise History. It’s published by Thames & Hudson as part of their World of Art Series, and is available now in the UK and in October from Amazon.com.

Here is s a sneak preview of the Preface:

It may come as a surprise that the predecessor to the present book in the renowned World of Art series is Sir Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting, first published in 1959, revised by Read in 1968, and finally reprinted with an additional concluding chapter by Caroline Tisdall and William Feaver in 1974. Read’s history assumes without question the importance of painting, or at least some forms of painting, as a vitally ‘modern’ art medium. One of the reasons for the delay in the appearance of a new survey in the World of Art series is that around the time Read published his book, and certainly when it was revised, painting’s status fell into question. The experimental impetus driving art forward, the desire to innovate, seemed to have ended up producing blank canvases, or near enough. At the same time, painting as a medium was condemned by the artistic avant- garde as outdated and too much of a commercial product. Instead, various conceptual practices that were anything but paintings took centre stage. But times have changed. Within contemporary art, paintings in many, many styles have secured valued places alongside a host of other practices that embrace radically expanded ideas about art.

Read began his history with the French artist Paul Cézanne – that is, in the late nineteenth century. This new volume starts about one hundred years earlier, with the emergence of Romanticism in European art. Read’s choice was primarily motivated by the fact that for him the honour of being called a modern painter was only to be awarded to those who made certain kinds of paintings. He argued that it was not enough for an artist to ‘belong to the history of art in our time’ in order to be described as ‘modern’ in the specific way he defined it. His narrative drew a line between late nineteenth-century Post- Impressionism and what came before, as well as a line around types of painting associated with less innovative styles that did not reject the conventions of optical realism forged in the Renaissance. Read saw ‘modern’ art as being geared towards challenging these conventions and dedicated to perpetual innovation – with one style trumping and making redundant what came before as art moved inexorably towards what Read described as the goal of ‘making visible’ rather than ‘reflecting’ the visible (which is what he assumed realistic painters did). In stylistic terms this boiled down to either abstract art and the repudiation of any obvious reference to the visible world, or the dreamlike imagery associated with Surrealism.

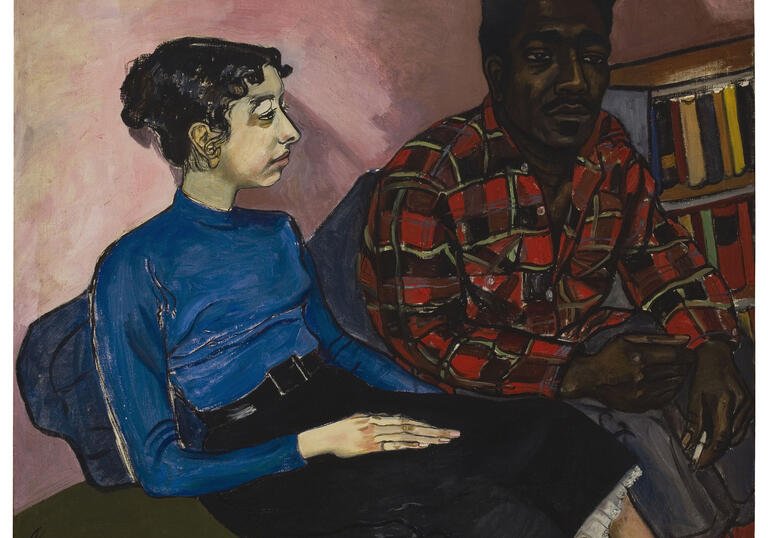

This new concise history tells a more inclusive story than Read’s, one that places painting in a broader stylistic, historical, geographical, and gender and ethnic frame. It is structured as a loose timeline. Where it seemed interesting to do so, I have quoted the words of the artists themselves, but I have avoided quoting from critics, theorists and art historians. At the end of the book there is an Appendix in the form of a series of questions that the reader might like to ask of the artists and the ideas discussed, but also of the text itself. This is followed by a Further Reading section for those that want to dig deeper.

I hope this new history allows the artists and paintings it discusses to be appreciated within a diverse and inclusive intellectual, historical and social framework. I am certain that, especially from the perspective of the new plural centres of the globalized

contemporary artworld, the story told in these pages will still look overtly centred on Europe and North America. But the concept of ‘modern art’ was born in Western Europe, and it is inextricably bound up with the forces of westernizing modernity. Furthermore, there is no escaping the fact that ‘‘art history’ as a genre is in itself a fundamentally western discipline invented for organizing cultural artefacts and their relationships within specific categories across time and space.

Finally, I want to stress that there is no substitute for knowledge by acquaintance. Only by seeing real paintings in museums and galleries will we be able to develop valuable relationships with them. This truth is especially important to recognize nowadays, since we are becoming more and more dependent on experiencing the world via digital media. While the Internet allows easy and free access to an unprecedented number of images of paintings, compensating generously the inevitable difficulties involved in seeing real ones, we should always remember that a photograph of a painting is just that, a small-scale, flat, synthetically coloured, digitally generated reproduction. But, more concerningly, a photograph of a painting on a screen or in a book displaces it into a context in which we experience it sitting down within the kinds of spaces that encourage the more cerebral or intellectual modes of thinking associated with word-based knowledge. Real paintings, by contrast, are meant to be experienced in three-dimensional environments within which we physically move around, and where we are open to more embodied, sensual forms of experience and knowledge.

Follow this link to order the book on Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Modern-Painting-Concise-History-World/dp/0500204896

‘SPECISME SEXISME RACISME LES VRAIS INVISIBLES!

While I was walking around the city of Bourges in central France, which is forty minutes north of the village where I have my house, and from where I’m writing this post, I noticed this prominently sited mural that declares: ‘SPECISME SEXISME RACISME LES VRAIS INVISIBLES! (Species-ism, Sexism, Racism The True Invisibles!) What especially struck me was the presence of the first term, which I hadn’t really considered so obviously a characteristic dimension of the by now other two familiar ‘systemic’ prejudices blighting society. But because of humanly driven climate change we are certainly going to hear much, much more about systemic ‘species-ism’.

While I was walking around the city of Bourges, which is forty minutes north of the village where I have my house in central France, and from where I’m writing this post, I noticed this prominently sited mural. It says on the left: ‘SPECISME SEXISME RACISME LES VRAIS INVISIBLES! (Species-ism, Sexism, Racism The True Invisibles!)

What especially struck me was the presence of the first term, which I hadn’t really considered so obviously a characteristic dimension of the ‘systemic’ prejudices blighting society. But because of humanly-driven climate change we are certainly going to hear much, much more about how our inter-species violence also extends to the trans-species - and beyond. When you line up ‘species-ism’ alongside ‘sexism’ and ‘racism’ you’re enlarging the case against humans to take into account violence not just against other humans but against other animals.

An online dictionary defines ‘species-ism’ or ‘speciesism’ as: “the assumption of human superiority leading to the exploitation of animals.” In this sense, it’s used by radical vegetarians who declare, for example, that ‘meat is murder’. But why stop at what we’ve done to fauna? Why not extend the condemnation to flora as well? Even to rocks and minerals and things like rivers and seas? After all, wide-scale environmental abuse is why we are now calling the epoch the Anthropocene. In the current cultural context, ‘species-ism’ is actually a sub-set of the wider malign legacy of civilization: anthropocentrism. We humans adopt an exploitative position in relation to the world by putting the interest of our own species first - at the centre. For millennia we have certainly been lording it over non-humans – other animals - but also the entire biosphere. The result is that we have brought the Earth to a potentially catastrophic precipice.

*

Humankind certainly seems to have a general tendency towards anthropomorphic projection. As the French anthropologist Philippe Descola observes, humans have “a propensity to interpret phenomena and behaviour observable in their natural environment by endowing non-humans with qualities that are similar to those of humans.” Indigenous peoples practice anthropomorphic projection, but as anthropologists have shown, they are not aggressively anthropocentric. For them, seeing the world anthropomorphically also means having specific obligations in relation to non-humans, the possibility of opening social relations with them. Descola describes what he terms “identification”:

It results from the fact that humans arrive in the world equipped with a certain kind of body and with a theory of mind, i.e. endowed with a specific biological complex of forms, functions, and substances, on the one hand, and with a capacity to attribute to others mental states identical to their own, on the other hand. This equipment allows us to proceed to identifications in the sense that it provides the elementary mechanism for recognising differences and similarities between self and other worldly objects, by inferring analogies and distinctions of appearances, behaviour and qualities between what I surmise I am and what I surmise the others are. In other words, the ontological status of the objects in my environment depends upon my capacity to posit or not, with regard to an indeterminate alter, an interiority and a physicality analogous to the ones I believe I am endowed with. I take interiority here in a deliberately vague sense that, according to the context, will refer to the attributes ordinarily associated with the soul, the mind, or consciousness – intentionality, subjectivity, reflexivity, the aptitude to dream – or to more abstract characteristics such as the idea that I share with an alter a same essence or origin. Physicality, by contrast, refers to form, substance, physiological, perceptual, sensory-motor, and proprioceptive processes, or even temperament as an expression of the influence of bodily humours.

Anthropocentrism is something else altogether. In effect, it drives a wedge between humans and everything else. This is how the Australian environmental philosopher Freya Mathews ( a recent discovery for me) describes it in The Dao of Civilization (2023) “ Anthropocentrism was the groundless belief, amounting to nothing more than a prejudice, that only human beings matter, morally speaking; to the extent that anything else – animals, plants, ecosystems, the natural world generally – matters, it does so only because it has some kind of utility for human beings.” Mathews traces anthropocentrism to as long ago as the Neolithic agrarian revolution, so as to understand how the animist focus of anthropomorphism, which is still evident in Indigenous cultures today, became perverted into anthropocentrism. As she writes in her most famous book, The Ecological Self (1991) once anthropocentrism was wedded to the mechanistic scientific worldview in the seventeenth century Europe, the recipe for ecological disaster was prepared: ‘from a mechanistic perspective, Nature is itself devoid of interests and is therefore indifferent, so to speak, to its own fate. Nothing that happens to it matters to it. It is in this sense, in itself, devoid of value.” A dualistic relationship was established between ‘nature’ (the non-human) and ‘culture’ (the human) within which ‘civilization’ became inherently exploitative and violent.

Clearly, an anthropocentric worldview is not so much the opposite of anthropomorphism as described by Descola in relation to the Indigenous worldview but rather a possible deviant consequence of anthropomorphism, one where the human capacity to project onto and identify with the world carries with it feelings of separation, superiority, and aggressive entitlement. The key point is that anthropomorphism in itself is surely a ‘good thing’ and certainly does not preclude the recognition that humans and non-humans are separated by differences of degree, not of kind. But how can we restore to anthropocentrism a less arrogantly controlling and more generously reciprocal attitude to the world within which we live?

Mathews and other environmentalists and ecologists urge us to shake of this malign anthropocentric relationship to the world and become instead ‘biocentric’ or ‘ecocentric’. The former stance implies we recognize living things carry equal and inherent value, while the latter extends this recognition to indicate that environmental systems as wholes carry inherent value. Both ‘-isms’ clearly seek to displace humans from the centre, where the centre is deemed to confer unique and superior status.

but I’m not sure making reference to the trio of species-ism, sexism, and racism is the right way forward. After all, wedding speciesi-sm with the other two potentially feeds the very anthropocentrism we’re supposed to be overcoming. In fact, one could argue that the more we ring our hands over the human cost to the environment, the more we draw attention to ourselves. So, in this sense, all we are indulging is a negative anthropocentrism. Maybe even nihilistic anthropocentrism. Also, when you think about it, calling a whole geological time period the ‘Anthropocene’ can seem like an extreme case of anthropocentrism: “Wow! We made it! We’ve finally put ourselves at the real centre. Well, at least, the centre of planet Earth.” Thankfully, there’s still a whole galaxy out there which knows absolutely nothing about a messed-up species of bipedal animals descended from apes.

REFERENCES

The Philippe Descola quote is from his essay ‘Human Natures’ in Quaderns (2011) 27, available on-line at: https://www.raco.cat/index.php/QuadernsICA/article/download/258367/351466

The Freya Mathews quote is from The Dao of Civilization. A Letter to China, published by Anthem Press, 2023. https://anthempress.com/on-the-dao-of-civilization-a-philosopher-s-letter-to-the-supreme-leader-pb

The Ecological Self is published by Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Ecological-Self/Mathews/p/book/9780367705183

The stained-glass of Bourges Cathedral

A post from central France, introducing what is, for me, one of the greatest works of art.

Saint-Étienne Cathedral, Bourges.

Since July 11th I’ve been staying in my house in the northern Allier region of France. Obviously, it’s always quite a culture shock to come back here after months in Korea. But rather than try to grapple in this post with some of the thoughts crashing around in my head, I thought I’d introduce a wonderful masterpiece.

Just up the road from the village where we have our house is the city of Bourges which has a cathedral named after Saint Étienne. It was built in the late twelfth to early thirteenth century in the early Gothic style. For me, the stained-glass windows around the ambulatory is one of the greatest works of art anywhere. Amazingly, 22 of the original 25 medieval windows have survived. Here are very inadequate photographs I took to give you some idea:

As the later windows one can see in Bourges’ Cathedral attest, the art of stained-glass was already extinct by the Renaissance, a salutary reminder that art media are closely related to wider cultural necessities. However hard modern artists have tried to make stained-glass for churches - Gerhard Richter’s window in Cologne Cathedral comes to mind, it is simply a fact that this medium is no longer potently contemporary. Here’s Richter’s work:

What I find especially satisfying in the Bourges’ stained-glass is that each window works on three distinct but interrelated levels. As you approach, you are first aware of the intricate and dazzling pattern produced by the tiny pieces of different coloured glass. Then, as you looks more consistently, you become aware of the division of the windows into symmetrical, geometric patterns. As you move up closer, you come to focus on the imagery and recognize (sometimes, anyway) the Biblical narratives narrated on each window.

This means you accumulate the contrasting aesthetic experiences of multicoloured and formless light and then the harmonious linear pattern. These experiences are then supplemented by the more discursive experience of reading the symbols and stories. But, of course, this transition doesn’t happen in strict linear succession, and you can flip back and forth between the levels as you move around in front of the stained-glass. That’s a pretty satisfying experiential ‘package’, one that spans a wide range of affective and cognitive skills.

*

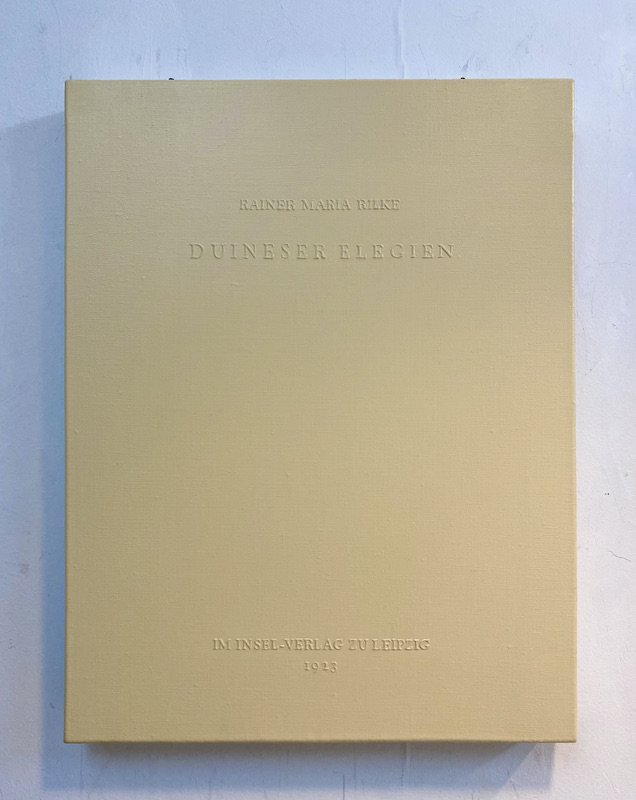

I realize that I try to achieve something similar in my own Book-Paintings. Here are some recent works. A book in German of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry collection ‘Duiner Elegein’ and one in French of Albert Camus’ ‘La Peste’. They are both 46 x 38cn, acrylic on canvas. Ther text is built up into relief and painted a very slightly different tone to the ground. In these cases, it is copied from the title pages of the original books:

As you approach the paintings from a distance, you at first see just a single coloured rectangle. The colours can be drawn from the original cover of the book or from an association I feel between the colour and the content of the book. As you move in closer you can make out the letters on the surface, which because they are in relief, cast a shadow on the surface. The text connect the painting to a specific book from which I have copied the typography and layout. You then read the painting and make associations to a work of literature and historical context. This means you move from a primarily sensory experience to a more cerebral one.

The word ‘move’ is crucial, because what this implies an animated relationship to the painting, as is also the case in relation to the Bourges’ stained-glass. For me, this animation, in which experiencing a painting means also engaging with through physical movements, movements, allows one to shift back and forth between different levels of response, is really important, as it works against the static idea of detached contemplation, which separates one from the thing contemplated.

Here are some more recent works, photographed in my Korea studio, made for a forthcoming show in London. The source of the two nearest paintings are monographs on British artists from the 1940s, published by Penguin. I played with the fact that the original design bisected the surface horizontally. The smaller works are derived from a novel by Virginia Woolf - ‘To the Lighthouse’ - and by D.H. Lawrence - ‘Sons and Lovers’. As you can surmise, the theme of the show is ‘Modern British’ art and literature.

NOTES

The photo of the Richter window is a screen grab from: https://www.design-is-fine.org/post/68822009029/gerhard-richter-cologne-cathedral-window-2007

‘A Nation of Racist Dwarfs’

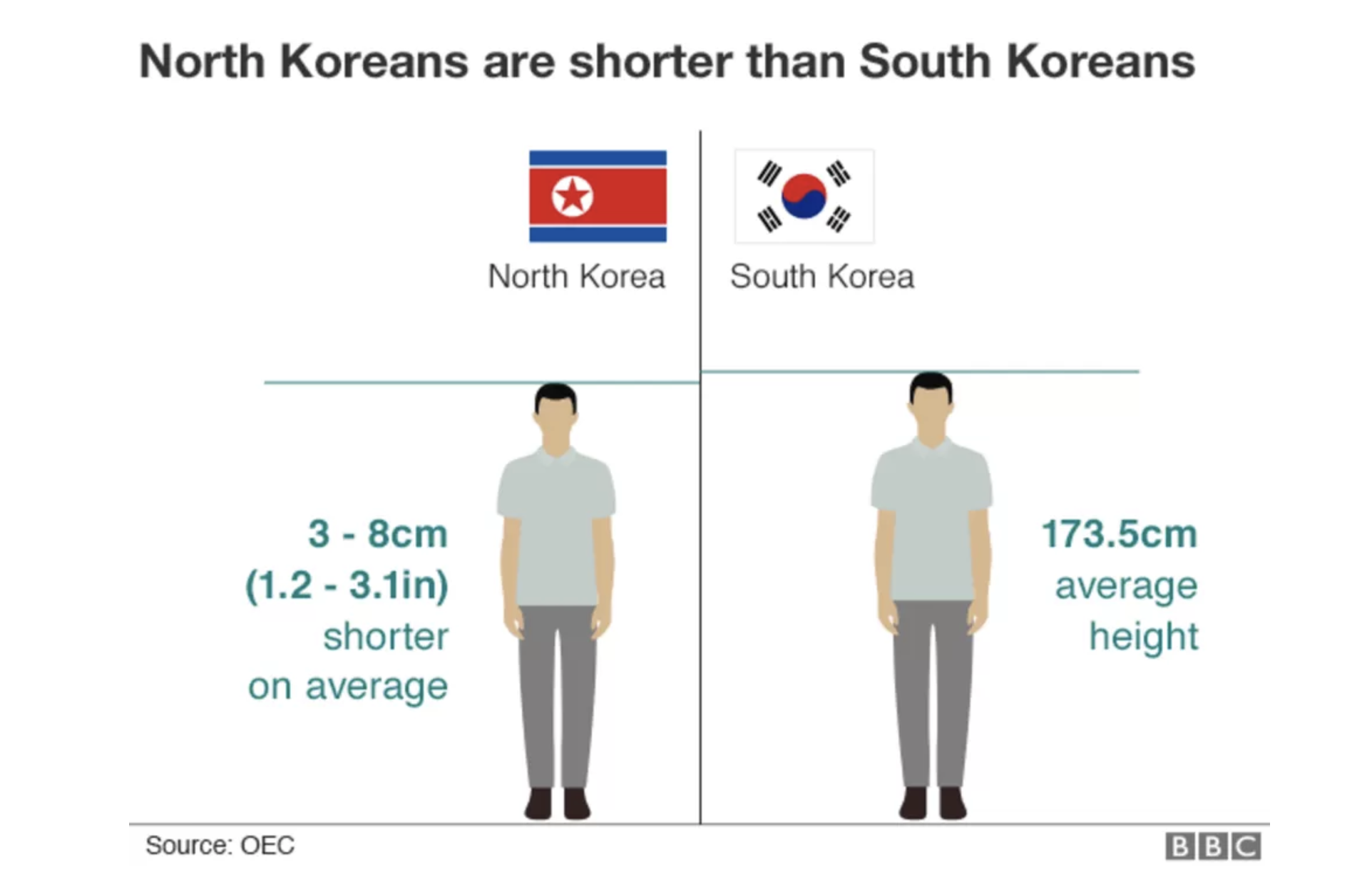

The title of today’s post is lifted from Christopher Hitchens’ essay from 2010 which I mentioned in my previous blog. Catchy isn’t it? And not a little racist, which is rather rich in that The Hitch makes a special point of describing North Korean as racist and xenophobic. He writes with authority that “a North Korean is on average six inches shorter than a South Korean”. But it’s not true! well, he was exaggerating. Find out how much.

The title of today’s post is lifted from Christopher Hitchens’ essay from 2010 which I mentioned in my previous blog. Catchy isn’t it? And not a little racist, which is rather rich in that The Hitch makes a special point of describing North Korean as racist and xenophobic. He writes with authority that “a North Korean is on average six inches shorter than a South Korean”, and goes on to invite us “to imagine how much surplus value has been wrung out of such a slave, and for how long, in order to feed and sustain the militarized crime family that completely owns both the country and its people.”

This data is shocking because while North Koreans got shorter, South Koreans got taller. But six inches (15.24 centimeters)? Are North Koreans (Hitchens doesn’t specify if he refers to a male or female) really that much shorter? The simple answer is no.

They are defintely shorter, but not nearly so much as Hitchens specifies. In 2002, the South Korean Research Institute of Standard and Science used United Nations survey data collected inside North Korea, and found that pre-school children raised in North Korea were up to 13 cm (5.1 inches) shorter and up to 7 kg lighter than children brought up in South Korea. Commentators put this down to the famine of the 1990s, which left one in every three children in North Korea chronically malnourished or 'stunted'. In 2006, the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention surveyed the physical condition of 1,075 North Korean defectors ranging in age from 20 to 39, and found that the average height of North Korean males was 165.6 centimeters (5 feet 5 inches), and North Korean females 154.9 centimeters (5 feet 1 inches). By comparison, an average South Korean man was 172.5 centimeters (5 feet six inches) tall and a woman 159.1 centimeters (5 feet 2.5 inches). The cause was clear: North Korea suffered from food shortages and the collapse of its public health and medical care system. In an essay from 2009 Professor Daniel Schwekendiek from Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul stated that North Korean adult men are, on average, between 3 to 8cm (1.2 to 3.1 inches) shorter than their South Korean counterparts. This is also the data on the BBC website (illustrated above) which says South Korean men are an average of 173.5 centimeters tall, and North Koreans are 3 to 8 centimeters shorter. But the most recent data I could find, at Wisevoter.com, puts the North Korean at 175 cm and a South Korean at 176cm. Just one centimeter apart! So, I really don’t know what the exact difference is!

So Hitchens was definitely exaggerating. But nevertheless, the height difference between North and South Korea is real and can only be put down to one thing: the political systems. In effect, the Korean peninsula is a tragic experiment in the impact on culture of biology.

This is what is called ‘epigenetic change’, which refers to environmental factors that impact on the human genome. The DNA sequence does not change but the organism's observable traits are modified. These epigenetic factors are typically described as external agents like heavy metals, pesticides, diesel exhaust, tobacco smoke, hormones, radioactivity, viruses and bacteria, or lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, stress, and sleep. One can also add political systems whose policies directly impact on what, how, when, and which people eat, what kind of medical care they receive, and what environmental agents people are or are not exposed to.

All these factors influence the expression of some genes, both positively and negatively. In the case of North Korea, mostly negatively. The variation of hieght is therefore graphic evidence on the most basic level of the regime’s abject failure. Maybe North Koreans are not ‘racist dwarfs’, but they certainly have paid a terrible physical price so that a vile clique can cling onto power.

To put the Korean statistics in perspective, here is some more data: an adult man in the UK is 178 cm average height, in the USA is 178 cm, and in France is 179cm (yes! taller on average that the Brits, which was shocking news to me, at least). The tallest human males in the world are Dutchmen at 184cm - an average 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) bigger than North Koreans.

*

Over the past two hundred years almost everyone in the world has been getting taller thanks to a better diet and medical care. As in Europe before the modern period, during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) Koreans adults were significantly shorter on average than today’s Koreans - Northern and Southern. According to the first nationwide study into the height of Koreans, including Joseon era Koreans, average heights of both male have increased by 12.9 centimeters (5 inches) and female adults by 11.6 centimeters (4.5 inches) over the past century.

But just as on the Korean peninsular today, history also shows that the trajectory is not always continuously upwards. Here’s something interesting I found while surfing for this post at OSU.edu: Northern European men had actually lost an average of 6.3 centimeters (2.5 inches) of height by the 1700s , and this loss that was not fully recovered until the first half of the 20th century!

A variety of factors contributed to the drop – and subsequent regain – in average height during the last millennium. These factors include climate change; the growth of cities and the resulting spread of communicable diseases; changes in political structures; and changes in agricultural production.

"Average height is a good way to measure the availability and consumption of basic necessities such as food, clothing, shelter, medical care and exposure to disease," [Richard] Steckel said. "Height is also sensitive to the degree of inequality between populations."

"These brief periods of warming disguised the long-term trend of cooler temperatures, so people were less likely to move to warmer regions and were more likely to stick with traditional farming methods that ultimately failed," he said. "Climate change was likely to have imposed serious economic and health costs on northern Europeans, which in turn may have caused a downward trend in average height."

Urbanization and the growth of trade gained considerable momentum in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Both brought people together, which encouraged the spread of disease. And global exploration and trade led to the worldwide diffusion of many diseases into previously isolated areas.

"Height studies for the late 18th and early 19th centuries show that large cities were particularly hazardous for health," Steckel said. "Urban centers were reservoirs for the spread of communicable diseases."

Inequality in Europe grew considerably during the 16th century and stayed high until the 20th century – the rich grew richer from soaring land rents while the poor paid higher prices for food, housing and land.

"In poor countries, or among the poor in moderate-income nations, large numbers of people are biologically stressed or deprived, which can lead to stunted growth," Steckel said. "It's plausible that growing inequality could have increased stress in ways that reduced average heights in the centuries immediately following the Middle Ages."

Political changes and strife also brought people together as well as put demand on resources.

"Wars decreased population density, which could be credited with improving health, but at a large cost of disrupting production and spreading disease," Steckel said. "Also, urbanization and inequality put increasing pressure on resources, which may have helped lead to a smaller stature."

Exactly why average height began to increase during the 18th and 19th centuries isn't completely clear, but Steckel surmises that climate change as well as improvements in agriculture helped.

"Increased height may have been due partly to the retreat of the Little Ice Age, which would have contributed to higher yields in agriculture. Also, improvements in agricultural productivity that began in the 18th century made food more plentiful to more people.

And here to finish are some famous people’s heights:

Bonaparte = 168cm.

Hitler = 174 cm.

Kim Jong-eun = 168.9 cm.

Putin = 169cm.

Trump = 184cm.

Interestingly, Hitchens (who died in 2011) was 175 cm tall,. That is, the same height as an average North Korean male today.

NOTES

The image at the start of this post is from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41228181

Christopher Hitchens article is at: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2010/02/kim-jong-il-s-regime-is-even-weirder-and-more-despicable-than-you-thought.html

Daniel Schwekendiek essay is at: ttps://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-biosocial-science/article/abs/height-and-weight-differences-between-north-and-south-korea/2EED5360F62997E3007425258C04A45A

The epigentics diagram is from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41440-019-0248-0

The data about Joseon era average heights is from: https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20120131000667

The quotation about average heights in Europe over the past three hundred years is at: https://news.osu.edu/men-from-early-middle-ages-were-nearly-as-tall-as-modern-people/

My list of famous people’s heights is from: https://www.celebheights.com/s/Kim-Jong-Un-49758.html

Wisevoter.com data is at: https://wisevoter.com/country-rankings/average-height-by-country/

‘North Korea: ‘a phenomenon of the very extreme and pathological right.’

The title of the post is a quotation from the British writer Christopher Hitchens, who wrote about the North Korean system in an article written in 2010. Hitchens began by recounting a visit to North Korea and how his minder had expressed racist views in such a way that it was obvious that such views were central to what, for him, was a quite normal and acceptable worldview. I think about how to understand this dreadful ideology within a wider context.

This photograph (not taken by me, although I’ve been there) shows North Korean border guards strutting their stuff just a few miles from where I’m writing this post, at Panmunjom, the only place where the DMZ narrows and the two Koreas meet. The title of today’s post is a quotation from the British writer Christopher Hitchens, who in 2010 wrote about the North Korean system in a much commented upon article. Hitchens began by recounting a visit to North Korea and how his minder had expressed racist views in such a way that it was obvious that these views were central to what for him was a quite normal and acceptable worldview. But his article was specifically motivated by reading the then recently published book by B. R. Myers entitled ‘The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves and Why It Matters’. As Hitchens wrote, Myers described “the Kim Jong-il system as a phenomenon of the very extreme and pathological right. It is based on totalitarian ‘military first’ mobilization, is maintained by slave labour, and instills an ideology of the most unapologetic racism and xenophobia.“

Since then, under Kim Jong-Ill’s successor, his son Kim Jong Un, things have only gotten worse in the DPRK, and many analysts would agree with Myers’ general prognosis. For example, it seems obvious that to persist in describing the country as ‘communist’ is very misleading, not least because the DPRK itself doesn’t use the word anymore! Ideologically, it prefers to refers to ‘Juche’ thought, which is usually translated as ‘self-reliance’ and is intended to be a specifically North Korean ideology - the one Myers’ set about describing. But it is interesting to consider how the term ‘communist’ was initially adopted and then discarded in the DPRK.

The North Korean regime was put in place by the Soviet Union, whose forces occupied the northern part of the peninsula at the end of World War Two. The first of the Kim dynasty, the former guerrilla fighter in China Kim Il-sung, was installed by Stalin as a counterpoint to the American candidate in the south, Syngman Rhee. This is an archive photograph from 1946 of people in Pyongyang parading with portraits of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Kim Il Sung:

Subsequently, two rival Koreans came into being in 1948. In 1950, Stalin gave Kim the ‘green light’ to invade the Republic of Korea. By that time, China had also fallen to the Communists. After the failure of the invasion and the stalemate of the Korean War, the DPRK settled into being a client state of the Soviet Union (and to a lesser extent, China) until the end of the Cold War in 1989 and the abandonment of communism in Russia precipitated a humanitarian and ideological crisis in the DPRK. But by that time the country had already moved to established its own distinctly ‘Korean’ ideology of Juche. It is this ideology that Hitchens characterised as being on the far ‘right’ politically because its racist and xenophobic traits are not ones that could be associated with the far ‘’left’.

But to what extent is this ‘left’/’right’ polarity an accurate way of analyzing the reality of North Korea over the past thirty years?

*

Following the French Revolution in 1789, when members of the National Assembly divided into supporters of the old order sat to the president's right and those of the revolution to the left, it became customary in the West (and then internationally) to described politics in terms of ‘left’ and ‘right’. In the nineteenth century Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels described ‘communism’ ’as a radical politics of the ‘left’ that recognized the historical inevitability of class war within capitalist societies leading to a revolution after which all property would be publicly owned and each person’s labour paid for according to ability and needs. It was therefore specifically cast as the antithesis to the ‘right-wing’ ideologies of the industrailized capitalist societies in which property was privately owned and labour rewarded unevenly and in relation to entrenched inequalities rooted in class and race. ‘Communism’ thus became the portmanteau term of the twentieth century for ‘leftist’ radical politics directed towards revolution from below, which, after the Bolshevik revolution in Russia 1917, was monopolized by the Soviet Communist Party.

But for post-colonial Korea, ‘communism’ meant something very different. It involved adopting one of the only two route maps towards modernization provided by the globally dominant West. Under the guidance of the United States the Republic of Korea had chosen the capitalist map, while the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea chose the communist one. It should be noted that neither map included democracy in Korea at this initial stage.

In relation to the communist road map, it is important to consider that Korea was also very far from being an industrialized economy against which a Korean ‘proletariat’ (the actually almost non-existent factory workers) - could be seen to be struggling for freedom against their capitalist overlords. In other words, as also, indeed, in Russia in 1917 and China in 1949, the ‘communists’ ostensibly took power in countries that Marx and Engels would have considered economically and socially distant from the ripe and predestined moment of violent revolutionary transition. Nevertheless, the communist road map was the only one handed to the North Koreans by the Soviets. But soon enough, as in Russia and China, ‘communism’ had morphed into a Korean-style totalitarianism of the ‘left’, as opposed to the totalitarianism characteristic of the ‘right’, aka fascism. That, at least, was how the story was told.

We still basically see politics today in terms of the binary ‘left’ and ‘right’, which is why Hitchens could imagine only a choice between seeing North Korea as on the extreme political ‘left’ ‘(communism) or extreme political ‘right’ (fascism) As racism and xenophobia were part of the fascist package, they placed North Korea on the ‘right.’ But this shoehorning into familiar political polarities risks losing sight of significant specific characteristics - but also characteristics of importance more generally beyond North Korea. For it is increasingly obvious that these polarities inherited from the European nineteenth century, never did fit the Korean situation, but also no longer suffice to describe the current political situation more generally - in both the global north and south.

*

Back in the late 1940s some disenchanted former communists wrote a book entitled ‘The God That failed’, edited by the Englishman Richard Crossman (a former communist turned Labour Party Member of Parliament). Subtitled ‘A Confession’, it included the testimonies of, amongst others, the Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler, the French novelist André Gide, and the English poet and critic Stephen Spender. The book was a classic of the early Cold War. I remember that my father, a state school English teacher and life-long socialist and Labour Party voter, owned a copy of the English edition, and I read it as a teenager in the mid-1970s, and it probably helped me steer a moderate ideological course during the awful Thatcher years.

Koestler joined the Communist Party in late 1931 and left in early 1938, and became a very vocal critic. He begins his contribution by writing: “A faith is not acquired by reasoning…..From the psychologist’s point of view, there is little difference between a revolutionary and a traditionalist faith. All true faith is uncompromising, radical, purist”.

Koestler’s analyses still seems spot on, because what we are witnessing today is an overwhelming tendency to adopt a position based not on reason but on ‘faith’, a position that is reassuringly ‘uncompromising, radical, purist”. We can see this trait on both the ostensible ‘left’ and ‘right’, and it suggest another polarity which offers a more accurate diagnosis of our current situation. The characteristics described by Koestler encompasses both extremes within our current ideological situation – ‘Woke’ radical race theory and nationalist populism - putting them not at opposite ends of a political binary of ‘left’ and ‘right’ but rather together within a binary comprised of ‘faith’ rather than ‘reason’ based politics. In this context, it’s not so much a problem of what one believes but whether such belief is ‘faith’ based intransigence – rooted in the desire to hold to the belief uncompromisingly, and so to adopt the most radical and pure possibility - or rooted in a reality that is recognized as inevitably ambiguous and uncertain.

Another work that made an impression on me as a teenager in the late 1970s – courtesy of my History teacher, Mr. Reid – was philosopher Karl Popper’s ‘The Open Society and Its Enemies’. This two-volume study was written during Popper’s exile from the Nazis in New Zealand during the War and published in 1945. Popper’s discussion of the Western history of ‘closed’ societies from Plato to Hegel and Marx was way too sophisticated for my young mind, but his basic argument was one that I did understand, and also one that still seems to resonate. Popper wrote:

This book raises issues that might not be apparent from the table of contents. It sketches some of the difficulties faced by our civilization — a civilization which might be perhaps described as aiming at humanness and reasonableness, at equality and freedom; a civilization which is still in its infancy, as it were, and which continues to grow in spite of the fact that it has been so often betrayed by so many of the intellectual leaders of mankind. It attempts to show that this civilization has not yet fully recovered from the shock of its birth — the transition from the tribal or "enclosed society," with its submission to magical forces, to the 'open society' which sets free the critical powers of man. It attempts to show that the shock of this transition is one of the factors that have made possible the rise of those reactionary movements which have tried, and still try, to overthrow civilization and to return to tribalism.

I recently read a fine book by the author and historian of ideas Johan Norberg called ‘Open. the Story of Human Progress’, which was published in 2020. Norberg credits Popper with defining a central class of values which he wishes to promote as a model for society today. He writes:

Openness created the modern world and propels it forwards, because the more open we are to ideas and innovations from where we don’t expect them, the more progress we will make. the philosopher Karl Popper called it the ‘open society’. It is the society that is open-ended, because it is not a organism, within one unifying idea, collective plan or utopian goal. The government’s role in an open society is to protect the search for better ideas, and people’s freedom to live by their individual plans and pursue their own goals, through a system of rules applied equally to all citizens. It is the government that abstains from ‘picking winners’ in culture, intellectual life, civil society and family life, as well as in business and technology. Instead, it gives everybody the right to experiment with new ideas and methods, and allows them to win if they fill a need, even if it threatens the incumbents. Therefore, the open society can never be finished. It is always a work in progress.

When read in the light of the regime now oppressing North Korea, what Popper and Norberg write provide useful insights. The regime is almost a caricature of the ‘closed’ society. But more broadly, they suggest that we should move on from the binary ‘left’ and ‘right’ and instead see the situation in terms of those who practice politics on the basis of ‘faith’ compared those doing it on the basis of ‘reason.’ Unfortunately, all too often a position based on dogmatic ‘faith’ is the more appealing option, as it means one doesn’t have to qualify one’s beliefs by taking into consideration conflicting attitudes, positions or information. In short, one can dispense with doubt. As Sam Harris puts it, ‘faith’ in this sense means ‘what credulity becomes when it finally achieves escape velocity from the constraints of terrestrial discourse - constraints like reasonableness, internal coherence, civility, and candor.’ Harris was aiming to expose religious faith, but what he says could equally apply to extreme secular ideological faiths, too. Isn’t North Korea a system that has definitely achieved ‘escape velocity from the constraints of terrestrial discourse’?

Ultimately, what we should be striving for is a way of thinking about society that incorporates doubt and that turns away from the temptations offered by any models - religious or secular - that try to banish doubt and install certainty. The terms ‘open’ and ‘closed’ seem to me to be useful titles of more realistic road maps than ‘left’ and ‘right.’

*

Norberg is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, DC, an organization that is often described as a hotbed of neoliberalism, and you can see how Norbert’s paean to ‘openness’ (like Popper’s) could easily be construed as providing a green light for capitalist free trade globalist maximalism. For Norberg’s optimistic version of the ‘open’ society seems wedded to an ideal of progress coupled to western style capitalism-driven globalization at a time when we recognize that it is precisely this ambition that has precipitated the dire global ecological crisis.

What would an ‘open’ society be like that isn’t founded on capitalist globalization and an obsession with progress in material terms, and instead was based on responding to what the philosopher Bruno Latour calls the ‘Terrestrial’, that is, on a kind of ‘openness’ to the planet as a whole, rather than just on narrow human needs and aspirations.

In 2018 the DPRK emitted 44.6 million tonnes of greenhouse gas, while the ROK emitted 758.1 million tonnes! So this particular ‘closed’ society is a far less brutal ecological force than the ostensibly ‘open’ one with which it shares the peninsula. But obviously, such a small carbon footprint has not been achieved by benign design, rather it came about by complete chance, and as a beneficial side-effect of being an unapologetically racist and xenophobic society. Ironic, isn’t it?

NOTES

The photo at the beginning of the post is a screen grab from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/north-korean-soldier-makes-midnight-dash-to-freedom-across-dmz/2019/08/01/69da5244-b412-11e9-acc8-1d847bacca73_story.html

The archive photograph: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1946-05-01_평양의_5.1절_기념_행사%282%29.jpg

Christopher Hitchens’ article:: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2010/02/kim-jong-il-s-regime-is-even-weirder-and-more-despicable-than-you-thought.html

B. R. Myers book: https://www.amazon.com/Cleanest-Race-Koreans-Themselves-Matters-ebook/dp/B004EWETZW

Johan Noberg’s book: https://www.amazon.com/Open-Story-Progress-Johan-Norberg/dp/1786497182

Sam Harris’ book ‘The End of Faith’: https://www.amazon.com/End-Faith-Religion-Terror-Future/dp/0393327655

The carbon footprint statistics are from: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/climate-action/what-we-do/climate-action-note/state-of-climate.html?gclid=EAIaIQobChMInsbXo4ng_wIVU4nCCh2UwgDbEAAYASAAEgKAQPD_BwE

‘Keep yourself alive’

There’s a trend in Korea amongst young people to take sets of four passport-like photographic ‘selfies’ in shops that are sprouting all over Seoul. I use this interesting phenomenon as a jumping off point for some reflections on the violent nature of image-making.

A glimpse into one of the many Box Photoism shops in Seoul

There’s a trend in Korea amongst young people to take sets of four passport-like photographic ‘selfies’ in shops that are sprouting all over Seoul. One chain is called Photoism Box. The picture at the beginning of this post shows one such outlet near Anguk station. Apparently, this trend is yet to invade the west and is a specifically Korean phenomenon.

It began in 2017 with a company called Life4Cut. Here is what Lee Da-Eun of Korea JoongAng Daily says: ‘This analog manner of taking photos grew immensely popular with young Koreans, and numerous studios such as Photogray, Photoism, Harufilm, Selfix and more hopped on the photo strip trend, known in Korea as four-cut photos. Although there are distinct features for each type of photo booth, there are some common characteristics. All of these booths offer natural photoshop features, special seasonal photo frames, unique photo props to enhance the experience and QR codes that provide a digital copy of the photos taken. ‘

The writer suggests three reasons for the growing trend: first, it offers a relatively cheap way to capture lasting memories with friends and loved ones; second, it’s an optimal self-promotion tool to be used on social media. The third reason is especially thought-provoking: ‘The photo booths also reflect Generation Z’s pursuit of a more “analog atmosphere” in contrast to their very digital lives. Gen Z, or people born between the mid-to-late 1990s to the early 2010s, are most likely immersed in digital culture and less familiar with analog photography. In Korea, however, the younger generation is increasingly interested in a more analog culture and atmosphere, as they pursue film photography and instant self-photo booths.’

Note the text on the window on the Photoism ‘Box’, at the bottom left of my photograph: “Keep yourself alive” (also note that it’s written in English, not Korean). Interesting! The phrase made me wonder about what is really at stake not just in relation to selfies but in photography in general. What the slogan obviously means is that a photo print is a more tangible memory than a digital file. It’s something you can hold in your hands. And even though you will probably post them online! This is the analogue experience that young Koreans are apparently craving. But let’s dig a little deeper.

In English we say ‘to capture’ something when we take a photograph. We also say, ‘to take’ a photograph, which on the face of it seems less violent than ‘capture’. But etymologically, the two verbs are closely related. The Online Etymology Dictionary says for ‘to take’: ‘"act of taking or seizing," 1540s, from French capture "a taking," from Latin captura "a taking" (especially of animals), from captus, past participle of capere "to take, hold, seize".’ In relation to ‘to take’ , the dictionary says the verb comes from ‘late Old English tacan "to take, seize," from a Scandinavian source (such as Old Norse taka "take, grasp, lay hold”)’.

These are very aggressive and predatory verbs being employed in relation to the act of using a mechanical optical imaging device to produce a representation of something. I wondered if it’s the same in Korean. Do they also conceptualize this activity using belligerent metaphors?

It seems the normal way to say ‘take a photograph’ in Korean is 사진을 찍다 (sajin-eul jjigda). The word jikgda relates to the way of describing stamping something, like a document, or printing a book or picture. The Korean is distantly related to the Chinese for a ‘seal’ on a document. But jikgda can also mean ‘hew’, ‘strike’, ‘chop’. So, there is also an albiet more attentuated belligerent connotation lurking in the Korean language.. But the verb also preserves a more overt link to the idea that a photograph is a stamp or print, that it is something tangible. This link is not necessarily carried over in the English convention of using the verbs ‘take’ or ‘capture’, which rather imply that we have actually possessed the something we represent, not just made a lasting impression of it.

In English we in part employ the same vocabulary in relation to photographs as was used previously to talk about handmade image-making, such as painting. We say, the artist ‘captured a likeness of someone’ in their portrait. But we don’t say to ‘take’ a painting. Rather, we say ‘make’, ‘produce’, or ‘create’. The choice of ‘take’ implies that the intermediary visualizing technology provides a directly indexical copy of the source (the subject to be photographed), and suggests the absence of active intervention or proactive work by the one taking the photograph. But either way, what is at stake is the underlying idea that an image somehow seizes its referent. It is not a gentle action. The idea of ‘keeping alive’ brings to mind the possibility that preserving memories like this really is a kind of capture or enslavement, and that the problem then is how to keep what one has photographed ‘alive’, how not to ‘kill’ it.. So, it really is a question of ‘keeping alive’, although, strictly speaking, it’s already too late. The image is already a corpse. For what we do when we document the world in images is simultaneously lose it. This is because reality is process, and an image inevitably cuts into the process. It freezes, ‘enslaves’, or ‘kills’ it. In other words, if making an image is violent, then the likelihood is that, despite our best intentions, what we ‘capture’ is being enslaved and also in danger of dying.

*

A consideration of the conditions experienced by our hunter-gatherer ancestors is helpful here, because evolutionary biologists have shown the extent to which we are 'haunted' by 'ghosts' of past evolutionary adaptions, that is, are hardwired to negotiate the world as it was experienced over tens of thousands of years, not just the mere hundreds of centuries of historical time. Hunter-gatherer societies are characterized by the absence of direct human control over the reproduction of the species they exploit, and have little or no control over the behaviour and distribution of food resources within their environments. Foraging for food was a fundamental survival skill, and the basic need for food played a fundamental role in the progressive evolution of cognitive structures and functions that would make food available on a more reliable basis. Under such conditions, humans explored their environments with the purpose of discovering resources of sometimes limited availability. The term ‘epistemic foraging’ is used in cognitive neuroscience to describe goal-directed search processes that respond to the state of uncertainty, and describes human behaviour considered not only in relation to specific task-dependent goals, like foraging for food, but also wider responses to the environment. This context-dependent behavior applied not only to the physical space in which humans existed but also to the abstract context of thoughts and decision making that helped humans to deal with uncertainty.. Foraging for information was as vital as foraging for food, as exploration resolved uncertainty about a scene. This ‘epistemic foraging’ supplied the core abstract thinking that humans developed, and gave them an evolutionary edge.

We are primarily geared towards the reduction of uncertainty through increasing our control over the environment, and we use epistemological tools to ensure this. But as Hartmut Rosa writes in his excellent book 'The Uncontrollability of the World’, human relationships to the world can be divided between on the one hand a stance of violent and aggressive action motivated by the will to mastery and control, to ‘capture’ and ‘take’, and on the other, one of erotic desire or libidinal interplay which requires a more open and accepting attitude to the uncontrollability of the world. Hunter-gatherer societies are characterised by the latter relationship, but within the culture of modernity, as Rosa writes, 'We are structurally compelled (from without) and culturally driven (from within) to turn the world into a point of aggression. It appears to us as something to be known, exploited, attained, appropriated, mastered, and controlled. And often this is not just about bringing things – segments of world – within reach, but about making them faster, easier, cheaper, more efficient, less resistant, more reliably controlled.' Rosa sees four dimensions to the modern obsession with guaranteeing maximum control: making the world visible and therefore knowable: expanding our knowledge of what is there, and making it physically reachable or accessible, making it manageable, and making it useful. But this sense of mastery comes at a high price because it lead to alienation from the world - to a loss of what Rosa calls 'resonance', which 'ultimately cannot be reconciled with the idea of intellectual, technological, moral, and economic mastery of the world.' As a result, we exist mostly in a condition of profound alienation, inwardly disconnected from other people and the world. As Rosa writes: 'Modernity stands at risk of no longer hearing the world and, for this very reason, losing its sense of itself.'*

Image-making is closely linked to the need to encode the results of epistemic foraging. But when seen in this light, a dual origin of image-making suggests itself. It began as way of encoding a libidinous and reciprocal relationship to the world, but gradually shifted to become a way of encoding the desire to enhance mastery and control. This could be described as image-making as as a system of engendering versus image-making as a system of production. This distinction is intended to contrasts two basic ways of being in the world: one in which representation encodes a world in in which we see the world as our dwelling place, and the other in which we are set apart in a position of aspiring (but inevitably futile) omnipotence. But image-making as engendering slowing gave way to image-making as production as we moved towards ‘modernity.’

What we humans fear most is uncertainty – being uncomfortably surprised. What we want most is to be in control. But in what does ‘control’ lie? Metaphors of ‘taking/capturing’ that dominate European languages in relation to making images, and those prevalent in Korean, suggest a common root in the idea of separation and aggressive domination and are infused with the aspiration towards control. But the western metaphors imply a far more aggressive relationship to the world than the Korea. The desire for control, which os a primary means of reducing uncertainty through closure is matched elsewhere by more open relationships to uncertainty.

The west seems especially inclined to the former. This can be seen in a very tangible way if we consider the evolution of the European artist’s’ self-image. From the sixteenth century onwards, their posture in their studios was made to look like this:

The preference for this stance, recorded here in a late sixteenth century Flemish print now in the British Museum, had much to do with the new social role-model then being adopted by artists, which was moving away from anonymous artisan or craftsman to being more like people on the next rank up in society: the knights. But this stance can also be understood to reflect the emerging idea central to modernity, which is that humanity is primarily characterized by the ability to assert aggressive control over the world. It is interesting to consider that this physical stance coincides with the start of belligerent European colonising of the world. It is also interesting to note that it is not seen anywhere else in relation to the self-representation of the artist. It certainly contrasts markedly with the self-image of the East Asian artist, who worked seated, poised over a horizontally oriented surface. This seems much more closely aligned metaphorically with someone sowing seeds in the earth - a farmer - that is, someone much more inclined to consider the world a dwelling place, not as a place for violent conquest.

NOTES

The Korea JoongAng Daily article can be found at: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/01/03/national/kcampus/korea-photobooth-photodrink/20230103190906442.html

Hartmut Rosa’s book, ‘The Uncontrollability of the World’ was published by Polity in 2020.

The illustrated print is an etching after Johannes Stradanus’ painting of van Eyck in his Studio, c.1590. It’s screen grab from the British Museum’s website.

Freeing the Mind, North Korea style

Some thoughts on what neuroscience’s insights into how the brain simulates a reality can tell us about North Korean-style thought control.

A North Korean with her smart phone.

Because I live so near to North Korea – from my roof I can see its mountains on the other side of the DMZ - it’s difficult for me not to think often about that brutally repressive regime, a preoccupation reinforced by the fact that it is very skillful in keeping itself in the international news (most recently in relation to a failed attempt to launch a satellite).

One thing that especially interests me, and therefore has been the theme of several posts, is the extraordinary level of indoctrination the government of North Korea successfully engages in. The fundamental prerequisite for this success is the isolation of the nation. This is both geographic and informational. Its closed physical and epistemological boundaries make possible a truly locally global control of the North Korean people’s minds.

In this post I want to think some more about this mind control in the light of research coming from the neurosciences into the way we now believe the human brain works. This research draws attention to the astonishing - and not a little unsettling - fact that our brains construct the perception we have of the self and of the world we inhabit. The success of the North Korean regime’s crazy system of mind control is only possible because of something basic all humans all share.

*

What the brain does is figure out the causes of the sensory data in order to get a grip on its environment. As the multi-disciplinary researcher Shamil Chandaria, a recent guest on Sam Harris’ wonderful Making Sense podcast, puts it: ‘most people’s common sense view is that we are looking out at the world from little windows at the front of our heads. But in fact, we are just receiving electrical signals, and the brain has never seen reality as it actually is.’ In other words, we make inferences about the world. We learn from all the data coming in, and infer what is going on, then generate internal simulations in the brain.

We simulate a picture of reality. ‘If I think I am seeing a tree, I then simulate the sensory data as if it was a tree’, says Chandaria. The result is that the past shapes our future because the simulation is based on prior experience. We make “top down” predictions about our sensory inputs based on a model of how they were created.

Aa a result, ‘conscious experience is like a tunnel’, writes the neurophilosopher Thomas Metzinger in his book The Ego Tunnel. The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self (2010) :

Modern neuroscience had demonstrated that the content of our conscious experience is not only an internal construct but also an extremely selective way of representing information. This is why it is a tunnel: What we see and hear, or what we feel and smell and taste, is only a small fraction of what actually exists out there. Our conscious model of reality is a low-dimensional projection of the inconceivably richer physical reality surrounding and sustaining us. Our sensory organs are limited: They evolved for reasons of survival, not for depicting the enormous wealth and richness of reality in all its unfathomable depth. Therefore, the on-going process of conscious experience is not so much an image of reality as a tunnel through reality.

This ‘ego tunnel’ is a result of the need to adapt to survive in complex environments which required that humans evolved to limit and restrict the range of potential points of view or emotions, thereby restraining the endless possibilities of the senses. In other words, ‘tunnel vision’ is an intrinsic part of ‘normal’ conscious experience.

From the point of view of evolutionary success, we need information about our place within the environment and the likely outcomes of our actions. The principal goal of the brain is therefore to maintain homeostasis - stable equilibrium within its environment. The most valuable states in terms of optimizing evolutionary adaptive success are therefore states that minimize surprise. It is vital for humans as adaptive agents to reduce the informational ‘surprise’ that is inevitably associated with our complex sensory engagements with the world, and reducing it enables the brain to resist the natural tendency toward chaotic disorder (entropy).

The level of the surprise we experience, and our ability to limit it through making predictions about our sensations, depends on the robustness of the brain’s internal generative model or simulation of the world. The discrepancy between ‘top-down’ predictions and the actuality and accuracy of ‘bottom-up’ sensations is called by neurologists ‘prediction error.’ These errors are minimized by converting prior beliefs and expectations, and these include not just what we sample from the world but also how the world is sampled.

The mental states that minimize surprise are those we most expect to frequent, and they are constrained by the form of the generative model we are using. In the field of neuroscience interested in what is know as ‘active inference’ , elements of environmental surprise are known as ‘free energy’. We minimize this energy by changing predictions and/or the predicted sensory inputs so as to resist the chaotic entropic forces suffusing the surprising. We revise inferences in the light of experience, updating ‘priors’ - memories - to reality-aligned ‘posteriors’, optimizing the complexity of our generative model of the world. ‘Free energy’ is thereby converted into ‘bound energy’.

The process through which we simulate past experience and ensure posterior beliefs align with newly sampled data is called in probability theory ‘Bayesian inference’ (after the theorem of eighteenth century statistician of that name). The ‘Bayesian brain’ is understood as an inference engine that aims to optimize probabilistic representations of what causes any given sensory input. Prediction error in relation to input is minimized by action and perception. Acting on the world reduces errors by selectively sampling sensations that are the least surprising. Perceptions are changed by belief updating, thereby changing internal states. The results are more reality-consonant predictions. If they are not updated, our predictions will not be consonant with reality. On an individual level, this failure may be caused by some trauma, for example, and can then manifest pathologically. But reality-dissonance can also happen on a group and societal level.

*

In this context, the North Korean system of mind control can be understood as a pathological inferential system that has exploited the profoundly human desire for homeostasis – for minimizing surprise. It aims to massively limit or bind the flow of ‘free energy’. But this means the obviously orchestrated and systematic ‘derangement’ of the North Korea people is only a very extreme case of something that is basic to how all humans make individual and collective sense of the world. As Chandaria notes: ‘You want a simulation that is as close to what you would normally expect before seeing the sensory data’. In the case of North Korea, the simulation is biased towards what the people have been conditioned to expect by the ‘top-down’ inferences disseminated by the regime’s total control of information.

When considered in this light, the recent Covid-19 pandemic was a ‘gift’ to the regime. It allowed it to greatly increase levels of isolation and restriction, closing off the country more than ever before. There has also been a major increase in crackdowns and punishments on foreign media consumption. For example, the 2020 anti-reactionary thought law has made watching foreign media punishable by 15 years in prison camp. But one can see why it is so vital that the regime keeps such a tight hold on the media. As a major conduit of ‘top-down’ information – ‘free energy’ - it is a threat to the homeostasis that guarantees the regime’s survival, the feeling of security manipulated by the regime in order to main its grip on power. One could say that it aims to ensure that any ‘bottom-up’ sensory input coming from the environment is conformed to the priors which are tightly controlled by the regime.

The Kim regime will stay in power as long as it maintains this monopoly on information flow. It is obvious, however, that this degree of global surveillance and control is quite simply impossible in a globalized and networked world. It is inevitable that the wall behind which the flow of ‘free energy’ is held will eventually be breached. And then what?

NOTES

Thomas Metzinger’s book, The Ego Tunnel is published by Basic Books: https://www.amazon.com/Ego-Tunnel-Science-Mind-Myth/dp/0465020690/ref=sr_1_1?crid=3OCZZB2OB1HAG&keywords=The+Ego+Tunnel&qid=1686294457&sprefix=the+ego+tunnel%2Caps%2C242&sr=8-1

Sam Harris’ podcast with Shamil Chandaria is at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FXs0uQ6M5ow

For more on active Inference, ‘free-energy’ and the Bayesian brain’ see: Karl J. Friston’s essay: https://www.uab.edu/medicine/cinl/images/KFriston_FreeEnergy_BrainTheory.pdf

For applications of ‘free energy’ and the ‘Bayesian brain’ to psychology see: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00592/full

The photo at the top of this post is from the Liberty in North Korea website: https://www.libertyinnorthkorea.org/blog/foreign-media-in-north-korea-how-kpop-is-challenging-the-regime?utm_medium=cpc&utm_source=google&utm_campaign=LINK-Blog&gad=1&gclid=CjwKCAjw-IWkBhBTEiwA2exyOy0EHeTr-0GSGeyv5lme5qTpYicJtpGeILjqimauZJg53nMHkW4c1xoCdikQAvD_BwE

Roses, Spring 2023!

It’s May, so that means the roses are in bloom throughout the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, including here in South Korea, and specifically, in my garden just a few miles from the DMZ.

It’s May, so that means the roses are in bloom throughout the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, including here in South Korea, and specifically, in my garden just a few miles from the DMZ.

Here are some pictures of roses in my garden. The first bloomer this year – on May 8th - was the native species rose Rosa Rugosa, the ‘Rugged Rugosa’:

Rosa Rugosa in my garden in Korea. It’s is a native of these parts. The first rose to bloom this year.

As you can see, the species variety of this rose has flowers that open wide to display five big purplish-red petals with bright yellow stamen. It repeats flowers, but each bloom only last a couple of days. The cane is very prickly, and there are big showy hips throughout late summer and autumn. Rugosa means wrinkly in Latin, and the terms refers to the characteristically corrugate leaves, which are dense and green, and turn golden yellow in late autumn.

The Rugosa is native to China, Korea, and Japan. In Chinese, the Rugosa is known simply as ‘meiguihua’ – simply, ‘rose’ – a sign of its predominance. In Japanese it is ‘hamanashi’ (‘Beach Aubergine’ – a reference to the large hips). Here in Korea they say ‘haedanghwa’ – (‘flower near the seashore’), a reference to the fact that the Rugosa can tolerate sandy soil and the salty air of the seaside. In Japan they were traditionally planted coastal areas to help stabilize beaches and dunes by retaining sand in the root cluster. Traditionally, it was used to make jam and various desserts, and as a pot-pourri. The Rugosa arrived in Europe from Japan in 1784, hence the primary association with that land, and the name ‘Ramanas’ seems to be a distortion of the Japanese name, which somehow metamorphised into ‘Hamanas’ and then into ‘Ramanas’. In the West, the Rugosa is also known colloquially as the ‘Letchberry’, ‘Beach Rose’, ‘Sea Rose’, ‘Salt-spray Rose’, ‘Japanese Rose’, ‘Ramanas Rose’, and, in the UK, the ‘Hedgehog Rose’ – on account of its thorniness. It is very useful as a hedging rose, and since its introduction in the West, has spread rampantly throughout Europe and North America, and in some regions is even considered an invasive pest.

There’s a wonderful poem by H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) about the Rugosa, entitled ‘Sea Rose’:

Rose, harsh rose,

marred and with stint of petals,

meagre flower, thin,

sparse of leaf,

more precious

than a wet rose

single on a stem—

you are caught in the drift.

Stunted, with small leaf,

you are flung on the sand,

you are lifted

in the crisp sand

that drives in the wind.

Can the spice-rose

drip such acrid fragrance

hardened in a leaf?

A couple of years ago we planted two specimens each of two Bourbon roses: ‘Louise Odier’ and ‘Variegata di Bologna’, which I was surprised to find on sale in a garden centre in south Seoul. Both are mid-nineteenth century European creations.The Bourbon family of roses probably originally came into being by chance - as a ‘sport’ in the botanical terminology - on a small island in the Indian Ocean, the French colony named Île Bourbon, renamed Réunion by the Revolutionary government in 1793. Eventually, seeds found their way from Réunion to Paris, where Bourbons were introduced to commerce in the 1820s with great success. By mid-century there were dozens of varieties, including my two examples. The consensus is that ‘Parsons’ Pink China’ crossed with a Damask while growing in a hedge on the island. As such, the Bourbon can be considered the first natural cross in modern times between an eastern and western rose, which occurred on ‘neutral’ territory, far from both.

The petals often make an almost perfect globe, and have an intense fragrance. is my ‘Variegata di Bologna’. As you can see, it gets it names from being bi-coloured (and being bred by an Italian):

‘Variegeta di Bologna’ in my garden.

Both my Bourbons can be purchased online from the British company David Austin Roses, the most famous rose breeders in the world today. Last year we planted one each of four different varieties of David Austin’s own ‘English roses’: ‘Gertrude Jekyll’, ‘Benjamin Britten’, ‘Generous Gardener’, and ‘Brother Cadfael’.

The “English Rose’ called ‘Gertrude Jekyll’ growing in my garden. Note how different each bloom looks.

‘Benjamin Britten’

The stunning ‘Brother Cadfael.’

“Generous Gardener’ being generous in my garden.

As you can tell from the names Austin gives his roses, the goal is to conjure up something very British, redolent with noble heritage and high culture. Or, sort of. Gertrude Jekyll was the doyen of late Victorian and Edwardian gardening and a great exponent of the rose and the ‘cottage garden’. Benjamin Britten was an twentieth century English composer, who is most well known for his operas. But check out his amazing String Quartets (see the link below). Brother Cadfael is a more contemporary, and at least for non-Brits or those too young to remember, more obscure , insofar as it’s named after a fictitious Welsh Benedictine monk living in western England in the twelfth century, the main character in a series of historical murder mysteries written during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, and televised starring Derek Jacobi. The somewhat unappealing name ‘Generous Gardener’, was apparently named for the National Gardens Scheme in the UK. But it's a gorgeous rose. As The David Austin website writes, it ‘bears beautifully formed flowers, which nod gracefully on the stem. When the petals open they expose numerous stamens, providing an almost water lily-like effect. The flowers are a pale glowing pink and have a delicious fragrance with aspects of Old Rose, musk.’

What Austin succeeded in achieving was the merging of the best and nostalgic qualities of the old garden roses, like the Bourbons, Damasks, Albas, Noisettes, Musks, etc., with the best of the new, like the Hybrid Tea and Floribunda, so as to produce a wonderful new family of roses that are typically characterised, like the one’s in my garden, by big generous blossoms and lovely fragrances, but also the capacity to repeat bloom and face extremes of weather, pests, and diseases better than earlier bred roses.

In my book By Any Other Names. A Cultural History of the Rose I quote David Austin himself, writing in 1988:

An English Rose is, or should be, a Shrub Rose. According to variety, it may be considerably larger or even smaller than a Hybrid Tea. But whether large or small, the aim is that it should have a natural, shrubby growth. The flowers themselves are in the various forms of the Old Roses: deep or shallow cup shapes; rosette shapes; semi-double or single, or in any of the unlimited variations between these. They nearly always have a strong fragrance, no less than that of the Old Roses, and their colours often tend towards pastel shades, although there are deep pinks, crimsons, purples and rich yellows.. The aim has been to develop in them a delicacy of appearance that is too often lacking in so many of the roses of our time; to catch something of that unique charm which we associate with Old Roses. Furthermore, English Roses nearly all repeat flower well under suitable conditions.

In fact, these days many of the ‘English Roses’ are not shrubs but climbers – both ‘Gertrude Jekyll’ and ‘Generous Gardner’ are, and in our garden at least, ‘Benjamin Britten’ seems to want to make its way up our trellis. But Austin has managed to revolutionize the rose for us contemporaries. In my book I call his rose ‘postmodern’, in the sense that Austin hybridised valued qualities of the old and the new.

Here’s a picture of another rose from my garden, the floribunda named ‘Simplicity’. This rose is a seriously promiscuous bloomer! I arranged some of its bounty in a bottle and put them in my studio. Recent paintings by me can be glimpsed behind.

As the website Ludwig’s Roses right observes, ‘The name ‘Simplicity’ refers not only to her clean, simplistic appearance but just as much to her simplistic growth habit – a very easy rose to grow.’

Incidentally, my book about the rose is about to be published in Korean, and I’ll write more about this when it’s available.

Notes

The H.D. poem can be found at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48188/sea-rose

Britten’s String Quartets can be heard at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y-Szv5TEBhg&list=PLexwM939sM9bHQEEllxm3tv9OPZXLs60u

David Austin’s quote is from The Heritage of the Rose (London: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1988), p.176

Ludwig’s Roses: https://www.ludwigsroses.co.za

Reflections on a photograph of a painting by Lee Ufan

An extract from a talk I recently gave about the problems of looking at paintings as photographs. I talks specifically about the Korean artists Lee Ufan.

Lee Ufan. Dialogue. 2014. Oil on canvas. 93 x 73 x 4cm. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

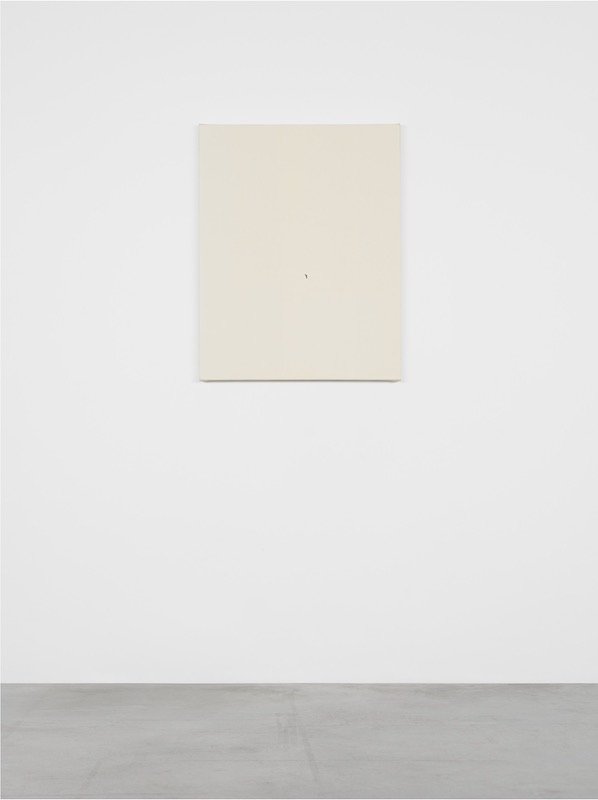

I recently participated in a symposium at Art Sonje Center in Seoul on the theme of ‘Painting in the Age of Digital Reproduction’. The symposium was part of a broader UK-Korea academic research project in which I’m involved which explores the materiality of painting - especially minimal ‘abstract’ painting - in a age dominated by digital reproductions. This is particularly interesting to me because of the paintings I make, like my ‘Book Paintings’, such as this recent one, based on the first edition of Freud’s ‘Future of an Illusion’:

Simon Morley, 'Freud.'Die Zukunft einer Illusion' (1928)', 2022, acrylic on canvas, 45 x 38cm.

As you can see, the painting is not easy to photograph! In fact, this inadequacy is intentional, because I want my paintings to be more about the intimate and tactile than the public and visual. Instead of a strong contrast between the text and the surface - as in the original book cover on which the painting is based - the colour is uniform and the contrast between text and surface is produced through small tonal difference and difference in texture.

Here is a version of part of the talk I gave in the symposium in which I discussed a painting by Lee Ufan, Dialogue(2014), which is illustrated at the start of this post. This painting featured in an exhibition we staged recently as part of the research project in London at the Korea Cultural Centre, called Transfer, in which a selection of Korean and British abstract paintings (including mine) were juxtaposed with video documents of the paintings. The digital ‘documents’ were specifically intended to avoid the obvious, ‘default’, kind of document which is a digital photograph like the of the Lee Ufan painting or mine shown above. The Lee painting is clearly very minimal indeed, and so it is all the more challenging to document photographically. Here it is as installed in the exhibition Transfer, alongside the video by the Belgian video and performance artist Rafaël, which was made as a decidedly unorthodox ‘document’ of the painting (more on the video below):

*